Scratch the surface of Lee Miller, and you'll find enough curiosities to keep you digging for a lifetime. That's certainly true for her son, Antony Penrose, who scarcely knew his mother while alive, and only discovered the details of her storied past when his wife unearthed a box of negatives, photographs and letters from his parent's attic.

Born in Poughkeepsie, New York, by 19-years-old the great adventure had begun when Miller was hoisted back from oncoming traffic by Condé Nast himself. Soon after, she graced the cover of Vogue and began a short career as a fashion model, which came to a halt when she starred in a campaign for Kotex. No matter, she once said "I’d rather take a picture than be one". With the intention of trying her hand at painting, Miller became a student at the Arts Students League, but came to the conclusion that all the best paintings had already been created. She turned to photography instead and sought out Man Ray in Paris to be his apprentice, becoming a muse to Jean Cocteau, a friend of Picasso, and a notable Surrealist photographer in her own right.

In the late 1930s she found herself married to Aziz Eloui Bey in Egypt but restless, she began reporting on the frontlines of WWII from Germany with Life photojournalist David E. Scherman. It's during this period that the pair snapped that infamous photograph in Hitler's bathtub. After the war, she came home to start a family with English artist, historian and poet, Roland Penrose. The adventure continued when she studied at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris and reinvented herself as a gourmet chef, which became her escape – her life, while glamorous and thrilling at times, was not without trauma.

Isolated, these accomplishments would amount to a life well-lived. Together, they are almost unbelievable and at least worthy of being immortalised in a Hollywood biopic – although that came earlier this year, with an adaptation of Penrose's biography with Kate Winslet as its lead. In celebration of Surrealist Lee Miller, a major survey of the photographer's work exhibited at the Heide Museum of Modern Art, RUSSH got on the line with Antony Penrose to discuss his mother's enormous legacy which almost went unacknowledged. Find our conversation, below.

You could definitely call your mother a Renaissance woman. She squeezed the juice out of life and lived boldly. What do you think fueled this nature of hers? Some have said it was a great restlessness...

It certainly was a great restlessness. I think it has a lot to do with an extreme trauma she experienced at the age of seven, when she was raped and left infected with Gonorrhoea. She had gone to stay with family friends and I think what happened to her psychologically, in that moment, was she realised that if she was going to be successful, she had to make the money. It was no good expecting other people to look after her, because they would inevitably fail, as they had here.

It was a mental conditioning that she had to make her own decisions, and go forth and grab what she wanted. She was a person with a huge imagination who could see all the possibilities, and she didn't want to be inhibited.

You had a complex relationship with your mother while she was alive. That shifted when your wife found her negatives and letters in storage. What was it like rediscovering your mother through her old photos? How did this change your understanding of who she was?

It was more a case of discovering rather than rediscovery because I hadn't known about her achievements, what she was like, or the incredible things she'd done because she hadn't shared any of it. I know she'd been a photographer, that she'd hung out with Man Ray, and shot a bit of fashion here and there. There were some odd photos around the house, but on the whole it completely escaped me – and that's how she wanted it. If people came around wanting to research her, she would deflect and talk about Man Ray or Edward Steichen.

It was a tremendous discovery and forced me to reevaluate my opinions of her.

Would you say you were curious about her growing up, or did you take her as she was?

Not really no, because she was actually somebody to be avoided when I was a child. She had tremendous mood swings, she was depressed, she was a difficult person to be around. She was never violent, but she could be emotionally and verbally cruel. I solved that problem by avoiding her – that was the best solution, so I hardly knew her at all.

I'm sure you would have many, but what questions do you wish you could ask her as you've gone through her life's work?

I have masses of small questions about places, dates, and time. But what I would really want to ask her is: can you tell me more about what drove you?

What was it that constituted that incredible drive? What was is that made you get on the line and go find Man Ray; that made you go start your own studio in New York; that made you go and marry Aziz Eloui Bey and live in Egypt, then leave Aziz and go and live in Berlin just as the war was beginning, for goodness sake? I just want to get a better understanding. It's easy for me to speculate that it was related to her childhood trauma, but if I had the opportunity to talk to her, that's what I'd want to discuss.

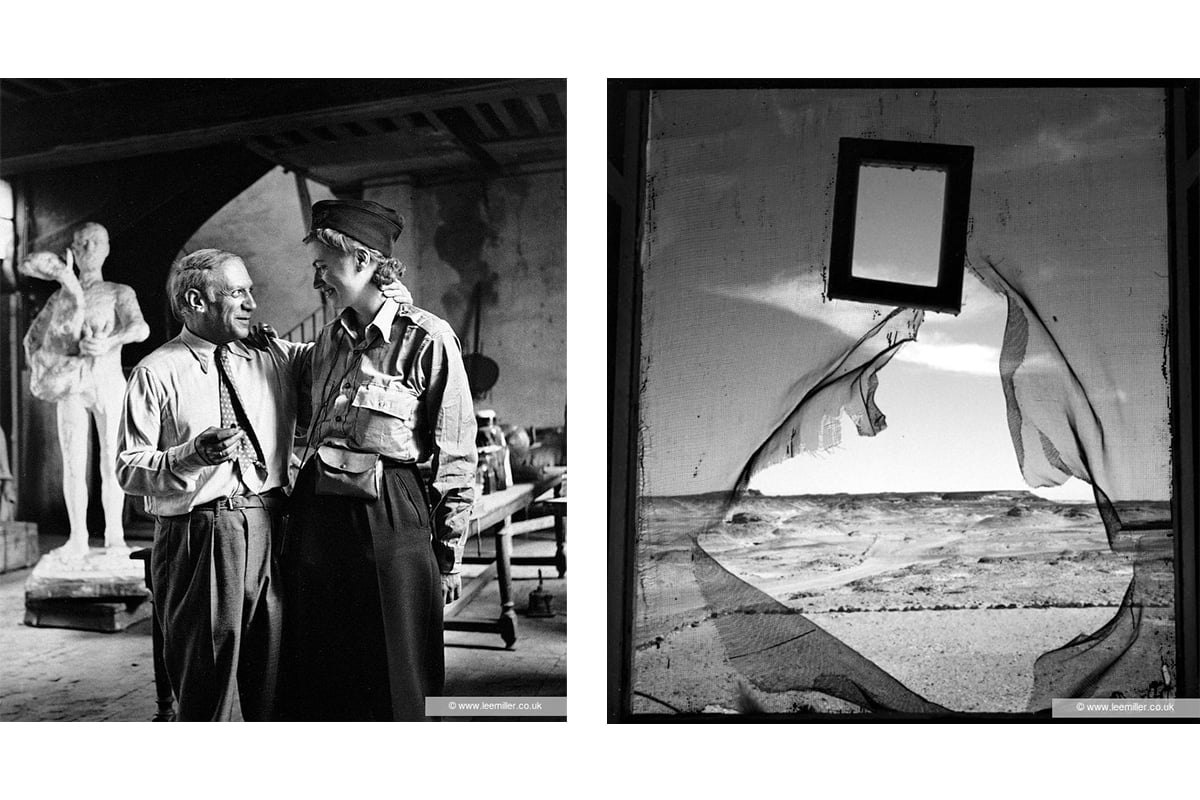

Left: Picasso and Lee Miller in his studio, Liberation of Paris, Rue des Grands Augustins, Paris, France 1944 by Lee Miller (NC0002-1) © Lee Miller Archives England 2023. All Rights Reserved. www.leemiller.co.uk. Right: Portrait of Space, Al Bulwayeb, near Siwa, Egypt 1937 by Lee Miller © Lee Miller Archives England 2023. All Rights Reserved. www.leemiller.co.uk

Left: Picasso and Lee Miller in his studio, Liberation of Paris, Rue des Grands Augustins, Paris, France 1944 by Lee Miller (NC0002-1) © Lee Miller Archives England 2023. All Rights Reserved. www.leemiller.co.uk. Right: Portrait of Space, Al Bulwayeb, near Siwa, Egypt 1937 by Lee Miller © Lee Miller Archives England 2023. All Rights Reserved. www.leemiller.co.uk

With the images in the recent exhibition at the Heide Museum, what stands out to you as the best reflection of your mother and her spirit?

I keep coming back to one image, which is called Portrait of Space (1937). It's a picture of the desert and beyond through a torn flyscreen. I think it symbolises her restlessness, what she used to call her "damned itchy feet". It's like she wants to burst through this restraining flyscreen and disappear down the track in the distance. There's this burning desire for freedom, which I think is symbolised through this cloud in the sky, which looks like a bird. In the other part of the flyscreen, the part that's not broken, is a rectangular hatch. That gives us the title, because it's like a portrait frame, framing space. That's her gift to you, that space is there for you to populate with your own dreams and your own imagining.

Can you tell me about the famous photo of Lee Miller in Hitler's bath. I know she'd just come back from Dachau, what's your interpretation of it?

There will always be a lot said of it, because it's not the kind of picture you can be indifferent to. What happened was this was the evening of the day that Lee had witnessed and photographed the liberation of Dachau. She and David Scherman had made their way through to Hitler's apartment, and they found that it was the only building in Munich that still had coals, so hot water. Scherman told me that they hadn't had their clothes off in three weeks, he said they stunk like polecats and this was too much; there was hot water, clean towels, and soap. Then they realised they had a scoop.

So they took a photograph from Hitler's apartment, it was a vanity portrait of him by his revolting pet photographer Heinrich Hoffmann. And they put this image on the edge of the tub, which was a wonderfully calculated insult. But the key to that photograph was the boots; because that morning those boots carried Lee Miller around Dachau, and now she's stamping the soot of that place, and that horror, and degradation into Hitler's nice, clean bath mat. And that proves she's not sitting there as a guest. But what she didn't know in that moment, was that Hitler and Eva Braun had committed suicide in their bunker that same afternoon.

And she never spoke to you about that period of her life?

She never talked about it. I think there were a number of reasons for this, namely that she wanted to leave it behind, which I think had a lot to do with suffering acutely from PTSD. We can recognise this now, but in those days not much was known about PTSD. Certainly, people found out by trial and error that some things were trigger factors, and I think she recognised that if she looked upon those images again, it would reawaken memories that were so painful to be unlivable.

She's often spoken about in relation to her proximity to Man Ray and Picasso, but I wonder what her relationship with herself was like. Did her backlog of works offer any insight?

She didn't keep a journal, sometimes she would make notes but that was it. It's an interesting question and it's one we have great difficulty with because she was a great keeper of secrets. Following her rape as a child, the family made sure nobody talked about it. It was this deeply held secret. I found out after she had died, only because her brother had broken ranks and told me. Suddenly everything became much clearer because I could understand her better. It also showed me her ability to keep secrets – not even my father knew about it. It shows how deep she was, and how many other secrets she kept as well.

She was a ship, and she had various watertight compartments and she never allowed those compartments to mix. It was this extraordinary self defence mechanism, because the thing was, back in those days the victim was always blamed.

Still from The Blood of a Poet, 1930 Jean Cocteau film

She became a great cook in her later years. Did this offer you an intimate glimpse of who she was?

I don't think many people had an intimate glimpse of her at all. Because the cooking, again, was a wonderful thing she loved doing, but it was also a distraction. It would save her from having to talk about anything more profound – I'm not saying she was a superficial person, but there were many things that were painful in her life, and rather than confront them with other people, she would just use it as a distraction to be the person who made these incredible surrealist-inspired dishes.

Is there a dish that reminds you of her?

There's a lot of them. There's one called Penroses, which was big mushrooms cut to look like roses, which were stuffed then grilled. Some of the other dishes I haven't had for many years. I always used to like Green Chicken. Then we had pink cauliflower breasts with a tiny little cherry tomato in a position you might expect. That was pretty yummy stuff.

My daughter, Ami Bouhassane, has created the Lee Miller cookbook, and in so doing, we had many tryouts of different things – some more successful than others.

People like Elizabeth David came along and introduced everyone to Mediterranean food, and Lee built on that. She was passionate about discovering dishes. So when she went travelling with my dad he would go off and do art things and she would disappear to go to restaurants or markets and come back with a whole selection of tins and ingredients.

Do you think she would've considered herself a feminist? Her actions certainly speak to this stance...

It's an interesting question. She didn't want to be an "ist" of any kind. She didn't like belonging to some kind of movement. She was a surrealist, and that did everything for her. Being a feminist or whatever else would not have appealed to her, because she didn't want to give her allegiance to an organisation. You see, she was very left wing but would've never become a communist.

She was distrustful of institutions. Do you think that came from her war reporting days?

Absolutely, it came from watching to rise of the Nazis.

Lee, the film based on your biography came out this year. Did you have any conversations with Kate Winslet, did you give her any instruction? What was the process of recreating Lee's life like?

I was very closely involved in the film. Kate is an absolute stickler for authenticity, she wants to get it right. She spent a long time in the Lee Miller Archive, sometimes it was just discussing things or looking through piles of photographs or contact sheets, other times we'd be looking at the cameras and the old uniforms. It was an immersive experience and I was full of admiration for her meticulous approach.

It must have been an uncanny experience see her in costume, because the resemblance between those two is really strong.

The first time I saw the film in its entirety, it absolutely blew me out because I thought she was there for real. I thought somebody had somehow found a way of filming my mum. It was so real; the dialogue, the voice tone, the appearance, the mannerisms. The illusion became the reality.

Installation view, Surrealist Lee Miller, Heide Museum of Modern Art, photograph: Clytie Meredith

You life has been in service of your mother's, and ensuring her legacy isn't forgotten. Outside of being your mother, what other reasons do you have to do this?

Well, first of all, I just love the material. I've always had a passion for photography, and in this case the photography is the very best and I love it for its own sake. More importantly, it is a fantastic opportunity. I would not normally have an opportunity to jet halfway across the world and work with the fantastic people at the Heide Museum of Modern Art.

I mean Lee wasn't much of a mum in her lifetime, but oh boy has she given me a tremendous gift in this life.

How has your mum's outlook influenced your own?

There are many things that I've taken away from her. One is the importance of always trying to be honest, and valuing honesty in other people. That is really significant. Also, to just go beyond, go beyond what is accepted as the normal parameters and limits.

Surrealist Lee Miller is exhibiting at Heide Museum of Modern Art until February 25, 2023.