“Art is nothing if you don’t reach every segment of the people.” - Keith Haring

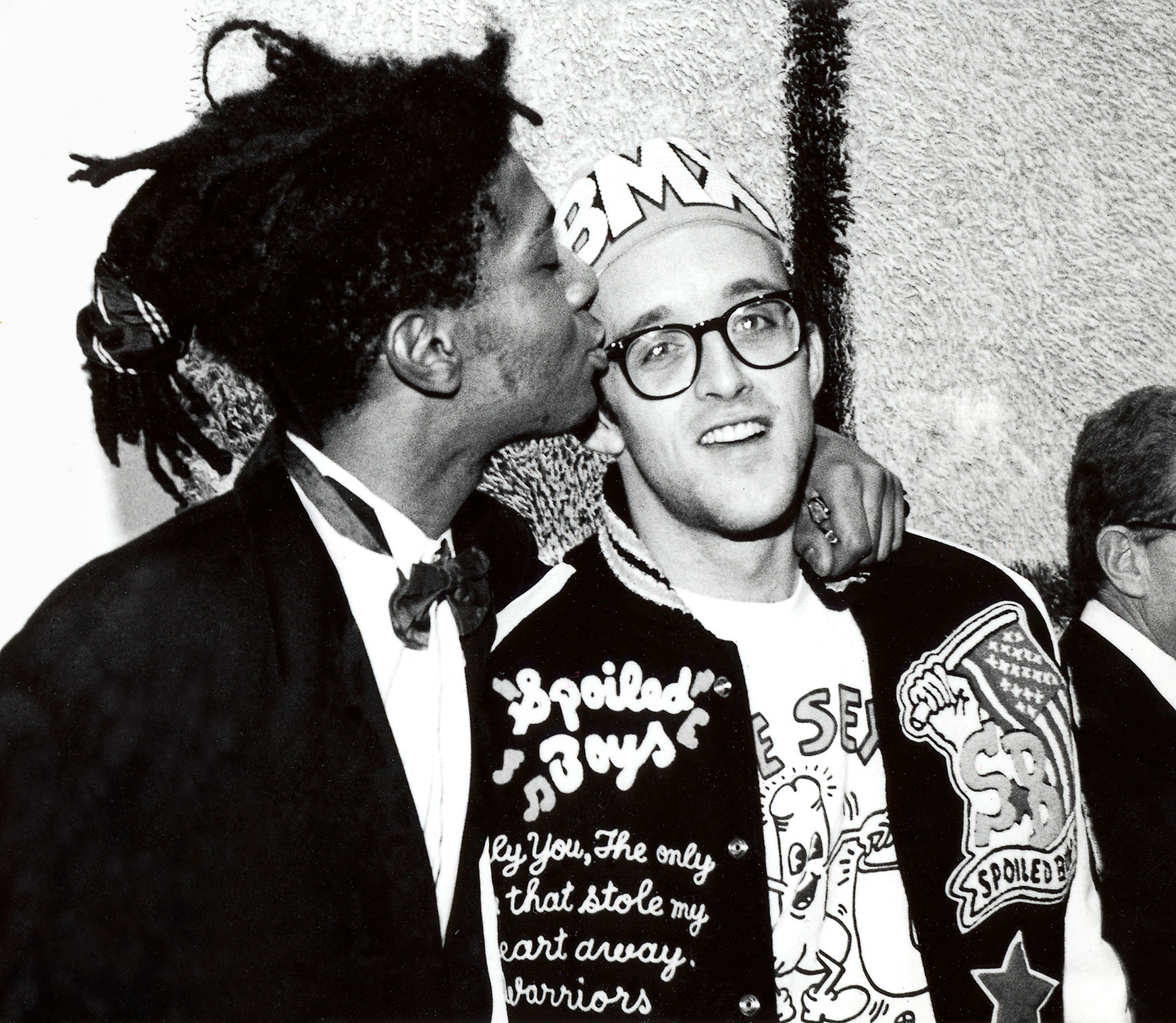

Two of the most authentic young artists of their time, Keith Haring (1958-90) and Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-88) took New York, and the world, by storm in the early 80s with their radical ideas, enigmatic street art and subsequent exhibitions. This year, exclusive to Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria will present Keith Haring + Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines, offering new insights into their unique artistic language and reveal the ever-present interweaving of their lives, works and ideas.

Though their artistic visions never joined on paper, their intersecting and tragically short lives continue to play an important role in the art world today. Colourful, mesmerising, political and utterly inexplicable - this is Haring and Basquiat.

Born in 1958, Keith Haring moved to New York at the age of 20, where the underground art scene was already thriving. Inspired by alt-culture and a burning passion to make art accessible, Haring took to the streets to express himself. From empty poster boards in subway stations to the walls of Manhattan and beyond, his iconic cartoonish figures were burnt into the minds of art lovers and commuters alike.

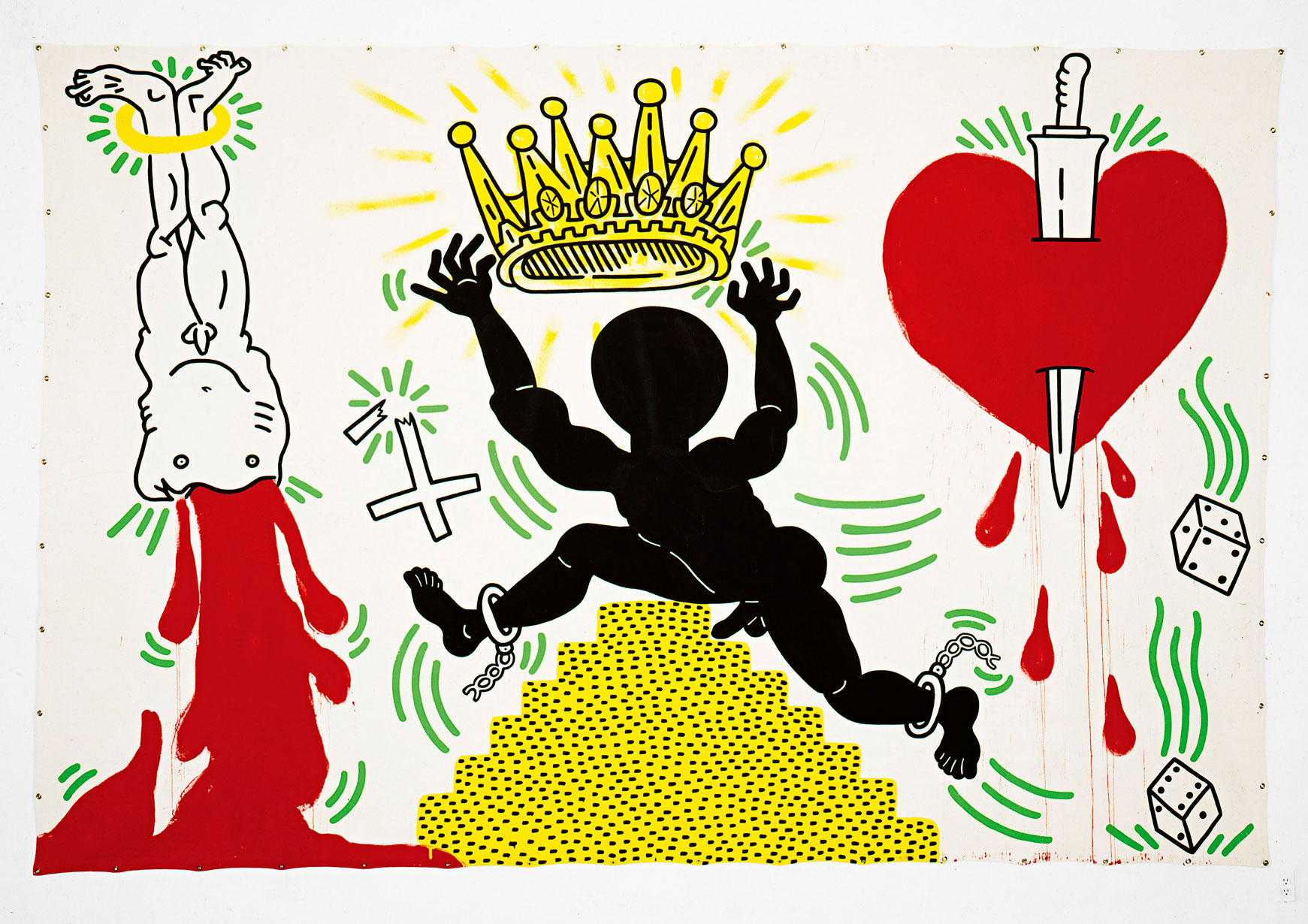

It was a rebellion against the status quo, or more directly, against the elitist fine art world that Haring believed was a discriminatory institution. His signature didactic images laden with thick black lines included the radiant baby, a barking dog, the dancing figures, the radiant heart and figures with televisions for heads, and were bursting with political and social charge. From the anti-drug mural in Harlem, CRACK IS WACK, to the Free South Africa poster of 1985, and the IGNORANCE = FEAR, SILENCE = DEATH art piece calling to de-stigmatise AIDS, Haring was not one to shy away from socially sensitive topics but rather charge at them paintbrush in-hand, adamant that his work be accessible to the masses in order to raise awareness.

Though many events connected Haring and Basquiat, one in particular would link the two forever. The death of a young black street artist, Michael Stewart, at the hands of the police led to a haze of outrage amongst New York’s artistic community – particularly for Haring and Basquiat who both started as graffiti artists blanketing the city with powerful phrases and images for years. Their subsequent tribute art to the death of the young artist was heavy with the pain experienced by the black community in America, as well as the society that knowingly adverted their eyes.

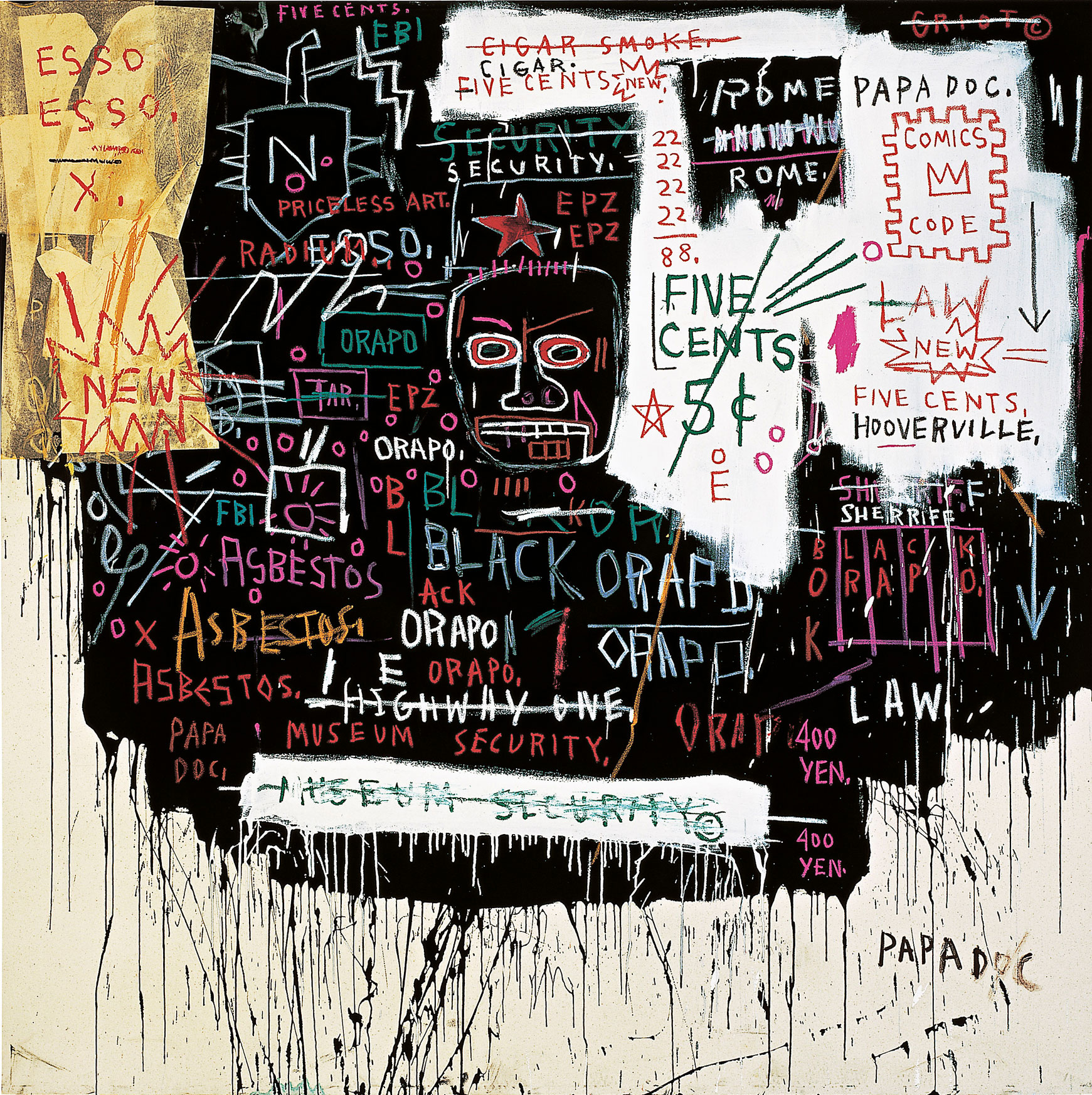

A Brooklyn native of Puerto Rica and Haitian heritage, Jean-Michel Basquiat was heavily influenced by each cultures art from a young age – learning to draw at his mother’s encouragement. A self-taught painter with art deeply rooted in the New York City graffiti movement, Basquiat cut his teeth in the art movement with friend, Al Diaz, under the nom de plume SAMO (short for ‘Same Old Shit’). It was the ultimate middle finger to the establishment, religion and politics that ruled society. Described as poetry, rather than graffiti, they pulled the rug out from under society. Much like Greco-Roman graffiti before them, it was commentary on the world around them, their view on an inherently racist, classist and conformist society. It was witty, confronting and mysterious and it got people’s attention

The genius that was the SAMO poetic graffiti movement was that it allowed Basquiat to channel his angst and fire shots at ‘the man’ and the art world, while simultaneously gaining entry into it.

Basquiat’s departure away from street art was nothing short of spectacular. After a short stint homeless, peddling hand-painted cards and t-shirts on the streets of New York, Basquiat was included in his first exhibition, a 1980 punk art show known as The Times Square Show. From that moment on his career took off with such haste that he was off the streets and soon immersing himself in the art world with the likes of Andy Warhol and Keith Haring.

By the mid-80s he was collaborating with Warhol, to whom he was incredibly close, and in ’86 he became the youngest artist to exhibit his work in Germany’s Kestner-Gesellschaft Gallery.

Playing off societies expectations of what a teen runaway was capable of, and shaped by his experiences, desires and upbringing, Basquiat’s art work was activism to the core; a comment on the society around him, especially the struggles of the black American experience.

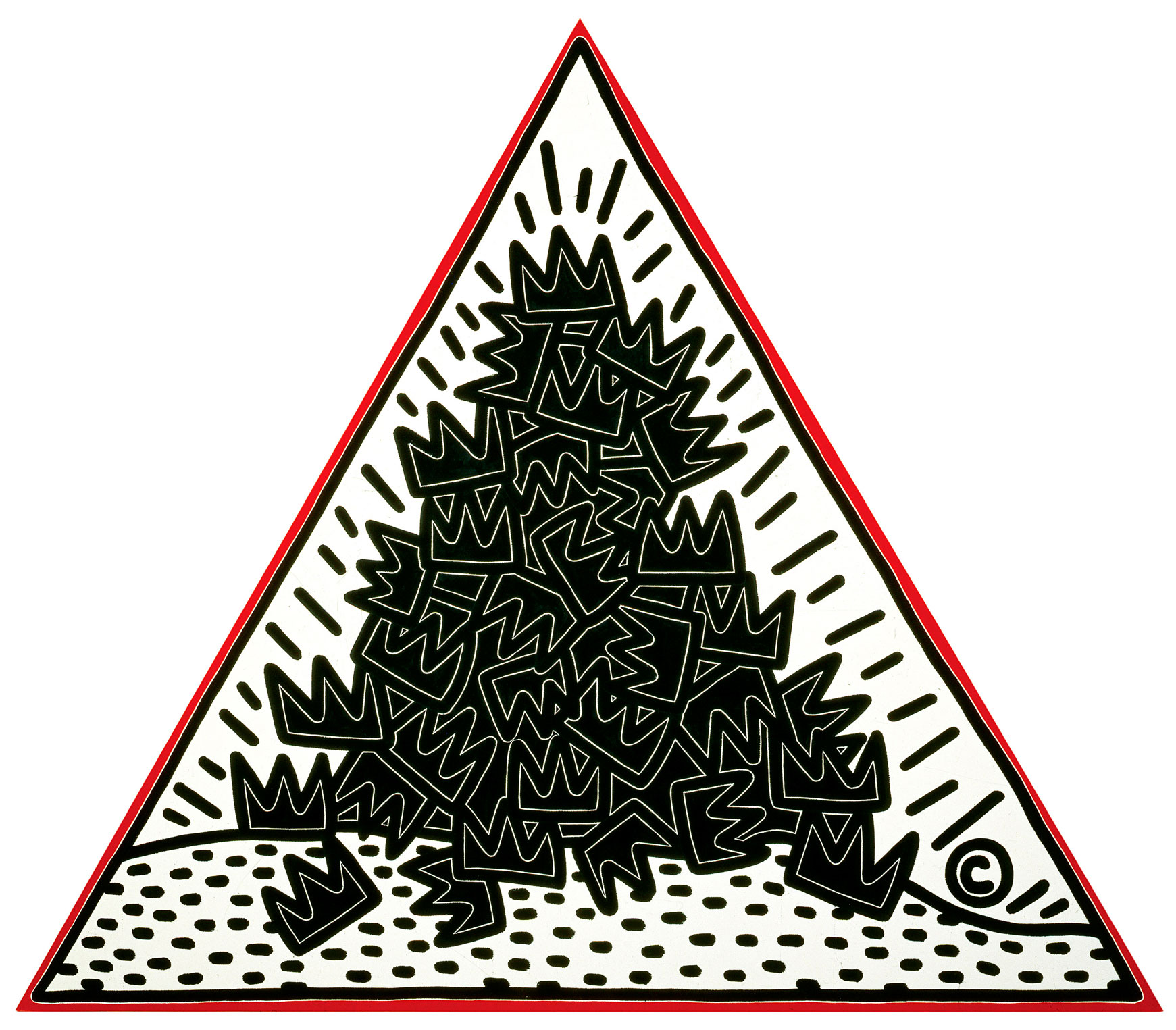

The most well-known motif to come out of his art is without a doubt the Basquiat crown. Reappearing time and time again, it is now a recognisable symbol in pop-culture. Gold with a thick black trim, it was a powerful logo in his timeless work and the perfect complement to his apparent fascination with the human head and skull, perhaps a comment on interplaying connection between intellect and the material world.

It’s the manic splatter of poetic words on canvas, the mastery of stray phrases, codes and symbols that makes his work so memorable. There is no other piece like a Basquiat piece. Never one to explain the meaning behind his art (“If you can’t figure it out, it’s your problem”), one could stand in front of a Basquiat piece for hours, and still not fully comprehend its complexities.

Haring and Basquiat lived shooting star lives, bright, memorable, if only for just a moment. They created for the people, not for an elitist, exclusive gallery or collector. Driven by societal issues and personal experiences, it’s the type of art that the world needs, the type of art that you can stand in front of and know it’s telling you something important.

Keith Haring + Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines runs through April 20, 2020.