In Winnie Dunn's earliest memories, a ngatu is always in frame. The ngatu is an intricate Tongan mat that can take years to form. To do so, women gather strips of mulberry bark which are then beaten and cut into thin ribbons, and later woven and painted as part of a communal effort. Dunn recalls her grandmother's ngatu spread across the front lawn and onto the sidewalk of their Liverpool housing commission home. Her nana would sit there for hours at a time painting designs onto the flattened fibre in 30-degree weather with a jumper on.

Making a ngatu is kind of like writing a book; bit by bit you tend to this project until one day you hold a manuscript. At least that's how Dunn framed the process of writing her debut novel Dirt Poor Islanders, which she started back in 2018. Maybe that's why the story opens with a ngatu too.

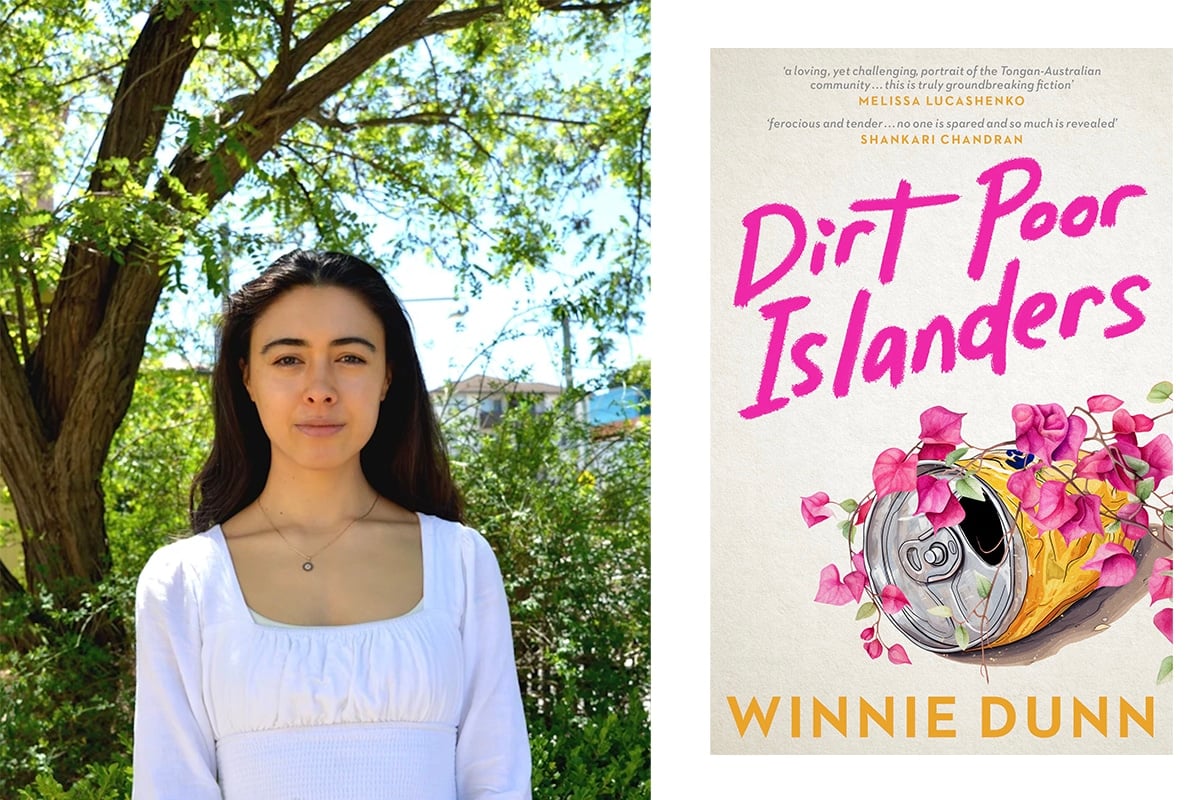

Dunn, who is the general manager of Sweatshop Literacy Movement and an editor of several anthologies, has written Australia's first novel about Pacific Islanders by a Pacific Islander. You see, Dunn is "hafekasi" – half Tongan, half white and like Meadow Reed, the teenage protagonist in Dirt Poor Islanders, she grew up in Mount Druitt. Also like Reed, Winnie Dunn's birth mother died while she was young and the author was raised by her grandmother and aunty. Curiously, there is no Tongan word for aunt or grandmother. Dunn explains, "every woman in your family is your mum and every male is your dad".

Every piece of writing is autobiographical fiction, insists Dunn. "We have this myth that the imagination is limitless, but it's not. In reality, our imagination is completely limited to what we know." But while Dunn shares similarities with her main character, Dirt Poor Islanders is not a memoir.

"Fiction gives me a lot more space to play. I can explore the essence of my life story, but not my actual life story," she says. Plus, the distance allowed Dunn to instil Meadow Reed with more agency than she had growing up. "She's much more vocal, more engaged and, I think, more mature in her responses."

This is important to Dunn, who feels indignant about the Pasifika representation she had growing up. It was Chris Lilley's brownface as Jonah Takalua in Summer Heights High and little else. In other words, a choice between flagrant racism or invisibility.

"Pālangi boys at my school would arrive dressed in a taʻovala, strumming a ukulele and repeating Chris Lilley's jokes," Dunn recalls. While in interviews Chris Lilley maintains he conducted research and community consultations, what Dunn saw play out was "the Jonah character empowering white men to take on other people's skin and culture".

"I remember it just made my skin feel really itchy," she says. "I think it was because I was embarrassed about my culture and my complexion. I wanted to get rid of it."

Six years ago, Winnie Dunn wrote an article for SBS Voices about the deep wounds Lilley's caricature inflicted not only on her, but other Pacific Islander Australians. That same article resurfaced in 2020 after Chris Lilley's shows were pulled from Netflix – around the time Dunn landed her book deal with Hachette. How's that for poetic justice?

Dirt Poor Islanders is separated into four sections – a format inspired by Maōri author Witi Ihimaera's 1987 novel The Whale Rider – and each section opens with a Tongan myth. Dunn wanted readers to experience Tongan culture not just in the modern sense but an ancient sense too "because being Islander isn't just Disney's Moana," she quips.

"I did it because although Australia is the closest neighbour to the South Pacific Islands, it doesn't want to know anything about us outside of football or farm workers or ONEFOUR. They're not interested in our history."

Getting started was overwhelming. Where do you begin with a story that has not yet been told? Dunn admits her first instinct was to "just write every single thing that happened to her ever". That urge was heightened by a feeling that it would be her one and only chance. Winnie Dunn chalks this up to the fact that "marginalised people, especially First Nations writers and people of colour, are so rarely presented with opportunities to have their work published or considered".

It's not enough to just be first. With Dirt Poor Islanders, Dunn is wedging her foot inside the door with the ambition that her efforts will result in a boom of Pasifika Australian stories. Already, we can see those narratives emerging from voices like Emily Havea, Ana Ika, independent publishing house Twinnies Brand, and I Am Lupe author Sela Ahosivi-Atiola, who assisted Dunn with fine-tuning the Tongan in her novel.

Ahosivi-Atiola was surprised by the depth of Dunn's cultural knowledge, pointing to specific ngatu patterns and myths she references in Dirt Poor Islanders. "Even our own community don't know these stories," she told Dunn. Winnie tells me this is because of the way Christianity swept Tonga after it was introduced and enforced by the British. Though Tonga was never colonised, spiritually Christianity had this effect, disrupting the oral tradition and resulting in knowledge gaps around Tonga's ancient history and culture.

But despite being a "staunch Christian", Winnie Dunn's grandmother would whisper these myths to her. Her aunty, Dunn's namesake and the person Dirt Poor Islanders is dedicated to, inherited her grandmother's rebellious streak, and that rubbed off on Dunn. Dirt Poor Islanders is as much a gift for Pasifika Australians as it's a revelation for white Australians too.

As for what's next for Winnie Dunn, the debut author believes it's important to hold off embarking on a new project until she receives feedback. She views it as an essential step in the collaborative process – and yes, writing a novel is a team effort. Dunn made a conscious effort to acknowledge the editors she worked with on the book, not only because she kicked off her career in the arts as an editor but from her experience "the way editors help shape a book and a story is really profound".

"You can't make a great story, or at least an original contribution to knowledge, without collaboration. It's how I learned to become a writer, surrounded by community at Sweatshop Literacy Movement," she concludes. "Because if you tried to make a ngatu on your own, it's going to be crooked."

Secure yourself a copy of Dirt Poor Islanders now. You can also catch Winnie Dunn on her Australian book tour, where she'll be interviewed by Amani Haydar in Sydney, Evelyn Araluen in Melbourne, and make a series of appearances at Sydney Writers Festival and Brisbane Writers Festival.