How is it that two identical states of being, that of being alone in a room, can be polarised by such dichotomous pain and pleasure?

A woman sits alone at a desk. She writes, but is she cathartically writing out the pain of her loneliness or is she celebrating her solitude?

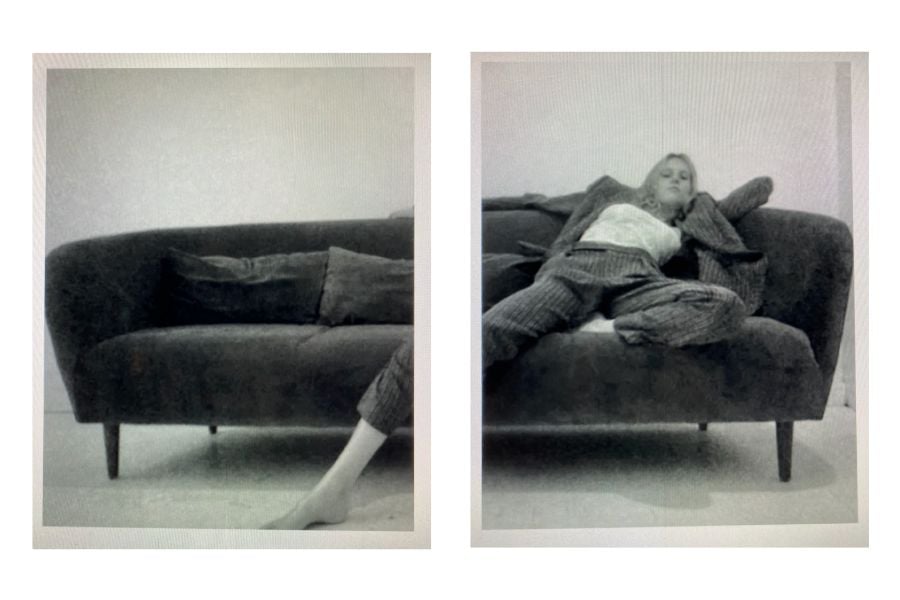

The inconsistency of humanity is a certainty when considering our need for others. We are fickle and oscillate between a wilful solitude and an imposed and fearful loneliness. Perhaps Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette expressed it most viscerally when she wrote; “There are days when solitude is a heady wine that intoxicates you with freedom, others when it is a bitter tonic, and still others when it is a poison that makes you beat your head against the wall.” The divide lies, as with most things, in our authorial intent: we choose solitude; loneliness is something that happens to us. However we do have agency in our perception.

In these unprecedented times, could we learn to create in isolation from the artists who did it first?

When we embrace solitude in order to create, it can take time and patience. Solitude doesn't provide immediate gratification in the same way throwing your arms around a loved one does, with that delivery of instant serotonin and oxytocin. The absence of touch in these trying times for the more romantic or sexual artists can cause a wilt in creativity, like an unwatered flower. Time in which we are forced to be alone can be confronting, daunting and uncomfortable. But even though we seem to resent it, separation - an esteemed room of one’s own - is deemed necessary. If what Picasso claimed is true, that “without great solitude no serious work is possible”, then how are we to come to terms with it?

Aristotle said we are either “beast or god” if we revel in solitude; we are completely sub or ultra human if we can handle a lack of society. Yet our access to divine comfort in our own homes is not so easily gained. Many of us carry the ghosts of imposed loneliness, haunted by times we were abandoned or forced out of a community of friends. We must sit often with the uncomfortable nature of being alone until, ideally, we enjoy our solitude.

I have often disparagingly said that I don’t want to be alone because I find myself such awfully dull company, but what I tend to mean is that my own company is deeply confronting.

There is a nakedness to being alone that terrifies me, and it is a physical feeling.

The director Ingmar Bergman puts this sensation to words most beautifully. He writes that he feels he has “too much humanity” when alone; that “[i]t oozes out of me like a broken tube of toothpaste; it doesn’t want to stay within the confines of my body. A strange feeling of weight and volume. Soul volume perhaps, which rises like clouds of smoke and envelops my body.” But is this a feeling we might learn to relish? Can we learn to enjoy the guttural and imposing aloneness if we re-see it as the cerebral freedom of a solitude enjoyed?

It seems to me that the language surrounding the situation helps to create the context. Very simply, the word ‘alone’ collocates with heartbreak and pain, yet to be ‘by oneself’ suggests peace and reflection. If language shapes the experience - from displeasure to relief - then, we should look at the words themselves.

In the 1670s, the English naturalist John Ray compiled a glossary of about one thousand irregular and infrequently used words, one of which was Loneliness. This early definition was a descriptor for people and places “far from neighbours”: so there were no negative connotations, just a geographical states. But art has caused loneliness to develop from a physical preposition to an internalised and emotional experience. One of the first examples of this comes with one of poetry’s most famous exiles, Lucifer in Milton’s Paradise Lost. When Milton wrote of the “lonely steps” of literature’s first pathetic outcast, Satan, the context and reception created a sense of pain for the exile and pathos in the reader. In our modern interpretation, we now read these “lonely steps” as an emotional stance rather than a crossing of a threshold, as though the word has gathered poignant meaning through the years of human experience.

If we take these words as free of their emotional burden and into a merely physical state, could this mean that loneliness is exploration of someplace external? And solitude, the positive of the respective pair discussed, is the enjoyable journey inwards? Historically, we find solitude linked to prayer, meditation and scholarly endeavours.

Is solitude an internalised wilderness which we must explore in order to be comfortable with our time with ourselves?

In his Letters to a Young Poet Rilke wrote of the need to enjoy this journey, advising to “Therefore, love your solitude and try to sing out with the pain it causes you. For those who are near you are far away. And this shows that the space around you is beginning to grow vast ... be happy about your growth.’ There is an acknowledgement that the eventual pain will metamorphose into self development.

As one of those aforementioned romantic artists, I have tried over the past weeks to dull my pain with my raison d’être. Perhaps seduction is key, at least for me, to this transformation from loneliness to solitude.

In lieu of a lover, my creative self has become the object of my affection as I seek to be romantic and kind.

In some ways, I have found this to be beneficial; flowers and whiskey on my desk, a collection of modernist love poetry and an absurdly romantic record has allowed me to feel content enough in my own company to write.

If we choose not to ward off our many thoughts and voices when physically alone, perhaps our solitude is company. By surrounding the act with warm connotations, we can avoid fear and self loathing that can accompany the lonely act of creation. We can drink the “heady wine”. Perhaps even become our own muse in the absence of another.

PHOTOGRAPHY Erinn Springer

FASHION & TALENT Elly McGaw

This article appeared in the 'Connection' issue. Find it here.