Dear Mum is an affecting story centred on matrilineal bonds, hope, pain and transformation. Tori Watts's story was voted by her peers as the tied winner for the People's Choice in the inaugural RUSSH Literary Showcase. Get to know her here, and keep reading to see her winning story.

What is the last book you read …

Lamisse and Hazem Hamouda’s The Shape of Dust. It's an integral read to understand the tenets of human faith and perseverance in the face of red tape, fierce injustices, and cruelty beyond measure.

What are you currently reading …

Bridget Hustwaite’s How to Endo. I was gifted two copies in the last week following my diagnosis last week. Processing a formal diagnosis is an often jagged, tumultuous, and grief-stricken pill to swallow. I’m finding solace where it can be found within these pages though.

What's your favourite book …

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong. I found it in a little bookstore in Ubud two years ago when I’d impulsively quit my job via FaceTime and decided to live in Indonesia for six weeks on a total whim.

The book that changed your life is …

Patti Smith’s Just Kids. It was actually ‘lent’ to me a few years back by a man I was momentarily dating, but he broke my laptop charger, so I never returned it to him (is all fair in love and war?).

What book would you give as a gift …

Nadine J. Cohen’s Everyone and Everything. My favourite holiday ritual is ignoring the stack of unread books at home and buying a new one at the airport. This was another book that fell into my grips exactly when I needed it.

Who inspires you...

Personally, my wonderful friend and close confidant, Solomon Kammer. Being a disabled artist doesn’t come without its own red tape, and access barriers to (say the least) and Solomon’s efforts to internally dismantle and advocate for others through their deeply personal works and other means is awe-inspiring. The first time I saw one of Sol’s paintings (four years ago), they were tattooing Lisa Simpson on my arm, and I lay eye to eye with both a person, and a story that would alter the trajectory of my own. I wouldn’t be the woman I am today without them; I owe so much to them for that.

Professionally speaking, it has to be Joan Didion!

The book everyone should read at least once is…

Chanel Contos’ Consent Laid Bare. In the current climate this book is a necessity.

What was the inspiration for your piece...

I think for those of us who know, the mother wound (which can take many different shapes and sizes as we saw with a lot of the submissions) is one that stays open for most, if not all of our lives. It’s just that it tends to interact with us depending on what we’re moving through, grieving, celebrating, achieving, and so on and so forth. I’ve always leant on writing as a therapeutic means for suturing my own wound and until very recently this was a largely private act. I knew that I wanted to submit something that was sincere and honest, and writing this piece felt both natural and inexplicably soothing. It felt like an act of bravery to sidestep the fear and give myself permission to speak to a facet of my life that has undoubtedly shaped me.

If others could do it, why couldn't I?

What kinds of stories do you most love to write...

Anything that explores a life experience, big or small, that I later learnt was a catalyst for change or deeper and more critical thinking. From poetry, to prose, to essays, I really enjoy giving myself an opportunity to deep dive on particular topics and later letting my mind run rampant with (peer-reviewed) thought.

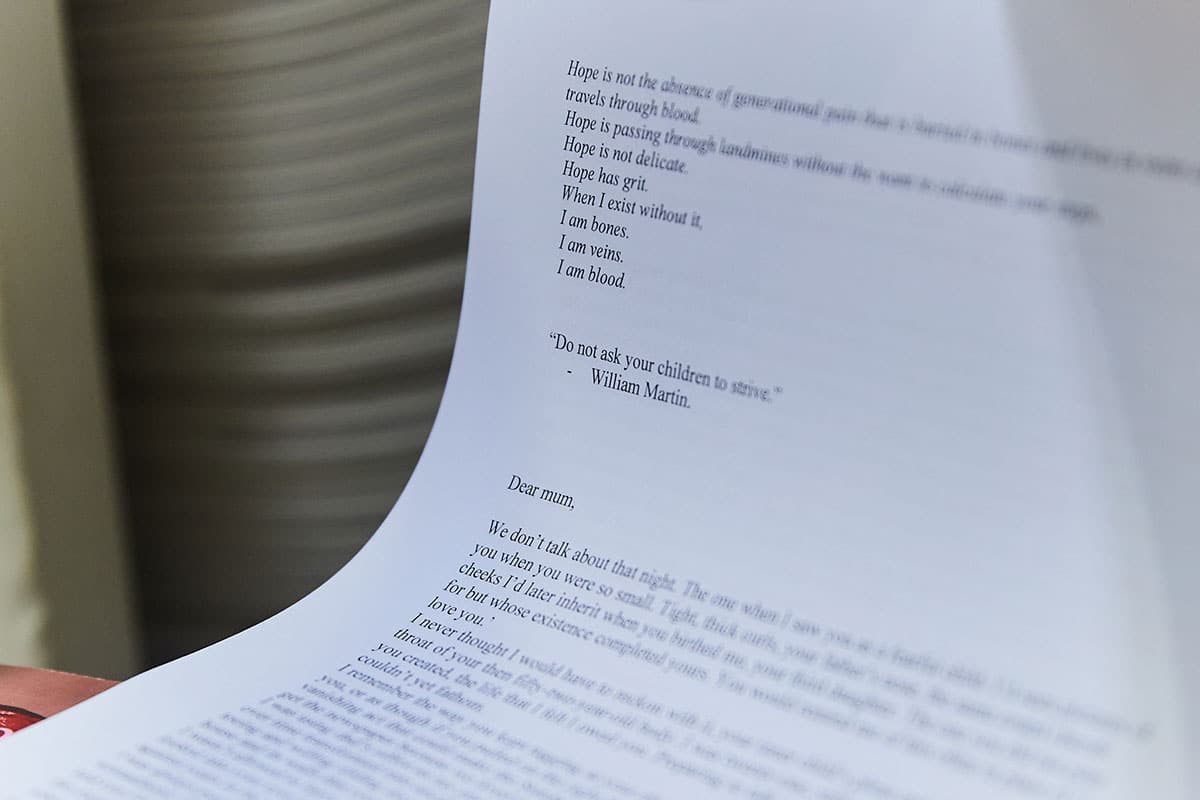

Dear Mum

“Hope is not the absence of generational pain that is buried in bones and lives in veins and travels through blood.

Hope is passing through landmines without the want to calculate your steps.

Hope is not delicate.

Hope has grit.

When I exist without it, I am bones. I am veins.

I am blood.”

Do not ask your children to strive

– William Martin

Dear Mum,

We don’t talk about that night. The one when I saw you as a fearful child. I’d seen pictures of you when you were so small. Tight, thick curls, your father’s nose, the same round cherub cheeks I’d later inherit when you birthed me, your third daughter. The one you did not plan for but whose existence completed yours. You would remind me of this often in place of ‘I love you.’

I never thought I would have to reckon with it, your inner child’s pleas manifesting in the throat of your then fifty-two- year-old body. I was twenty-one, still growing into the body that you created, the life that I felt I owed you. Preparing to talk you down from a ledge that I couldn’t yet fathom.

I remember the way you kept tugging at your sleeves, like you wished they would envelop you, or as though if you pulled on the right thread you would disappear on the spot. A vanishing act that could make the Sunday Times’ headlines and I’d be grateful that we didn’t get the newspaper because we lived in the hills.

I was using Dad’s office as my place of respite that night. The one next to the shed that had over time transformed into another bedroom. Mimicking his moves by way of laboured tip toeing and willing sliding doors to be silent. Trying to place enough distance between our house and its walls that could they have spoken, would have wailed. But it wasn’t far enough. I wasn’t allowed to leave the house that night. There was no gun to my head but when I looked into your eyes I saw how shallow the pool of your life was around you. Saw the gun against yours in the reflection of your water’s unmoving body.

I was always perplexed by the limits you enforced on my impending adulthood, my womanhood. How you celebrated my body when I came home from school in year five and I told you I’d gotten my period. I was a woman now, you told me. Though I did not know what this meant. How you later shamed it the day you found my first vibrator hidden under my bed when I was twenty because we’d blinked and metamorphized into strangers, and you would pry through my private spaces in attempts to answer the questions you had but couldn’t bring yourself to ask me. But I thought I was a woman; one with desire and longing and a heartbeat and a body that could sweat at the hands of my own. Wasn’t I supposed to learn the landscapes and the rolling hills of myself before somebody else crossed the threshold to study these spaces? I don’t know who taught me that.

"I begged and pleaded back at you and saw the animal in myself."

You learnt how to stretch those limits with the force and velocity of a conductor. Directing the pace and performance in my acts of being your baby at the grocery store long after I’d outgrown the red front seat in the trolley. Later being forced to outgrow you in my acts of being your caretaker when you needed to be tended to. When you needed to be nurtured and cooed at, the way only a mother knows with a mother’s soft speech and touch. A whispered will when necessary, to protect their young at all costs. When you needed to be mothered because you never were, but you were not my young.

I don’t remember phoning triple zero that night, waiting for the prompts and selecting ‘ambulance’ after you’d found me hiding in dad’s quarters and forced the sliding door open with your fingers gripped around your sleeves. But I’ll never forget your voice breaking in your attempts to plead with me not to let them take you as we stood at the bottom of the driveway in front of two uniformed men. It was guttural, subhuman, the way the noises escaped your mouth. The way I’d imagine a mother sea lion cries with a pain so visceral when she is stripped of her baby. Animal-like. Yet it was the most human I had ever seen you. I begged and pleaded back at you and saw the animal in myself. I walked back up our steep driveway alone and locked the office door behind me, afraid that the animals would find me in my sleep. And in a way, they did. I woke in the night in the bed that did not belong in an office. The hum of the computer’s monitor a tangible marker of homesickness despite being metres away from ours – the kind you feel as a child in the pit of your stomach when you have your first sleepover and lay your head on a pillow that smells differently to your own; when you long for your mother. I was in Dad’s place of hiding, his home of reprieve that I was trying to make my own with the sheets that you had washed, the matching mugs that you had purchased, piled up and stained with rings, marked with residual sugar granules he had not bothered to stir in. Palpable reminders that he’d been there days before his mind got the better of him.

“I was still twenty-one, still growing into the body that you created, the life that I felt I owed you.”

I was both longing for and grieving you. Carrying with me in the pit of my stomach knots that could never be known to a child, because children don’t beg for their mothers to leave. To live. Mothers don’t ask their daughters to carry their hurt. To live for them. Do you remember how you appeared hours later? My wrists were still tender from the grip you held on to them with, and my ears were still ringing from your pleas. You trudged back up our driveway and, though it couldn’t have been possible, you looked even smaller than you did before. I took you to bed, stepped into our house with the wailing walls and they struck me with a particular breed of nostalgia that only exists when you’re aware you’re on the precipice of losing what’s right in front of you. We never were good with effortlessly slipping into our designated roles. We were constantly swapping hats.

Mum, I never asked you if the uniformed men who watched you shapeshift in front of me brought you to the same hospital as Dad that night. If a stroke of fate had forced each of your hands to hold mirrors to each other, to see the monsters you had created in the mother-tongue of our house: silence. I imagined him speaking to the nurses about the neon overhead lights. How many he’d handled and installed in hospital rooms with beds waiting for the bodies of patients. How, in his navy work shirts with his business name proudly embroidered into them that you washed and ironed, he’d fought against hot crawl spaces and cobwebs so that you could fight against five hungry stomachs each night. How he wouldn’t have admitted to the nurses how different the overhead lights look when you’re surrendered to laying underneath them. Nobody knew how unwell he had become until his devotion to abandoning the Tupperware in our shack was heard by the neighbours, Mum. The house he ran to when the animals found a way to penetrate the brittle forcefield of the sliding door in his office. The house you bought together as a bandage because you won money you would later lose, because you thought the mother-tongue could abstain itself if it were away from the wailing walls. But those walls learnt to weep too. I would run my hands over the dining table with the ring marks burnt into them and myself and remember how you loved me. I would load wood into the fireplace, praying that the shadows of our former selves would move across the living room until the embers burnt out. I would lay underneath the jetty on my back and see where I etched the shortened version of my name, which I offered to myself in an attempt to shake everything that came with the one you gave me. Mum, you called me Maddy, and dad called me Minkie, but my name doesn’t start with an M, and anyway I have moulded the one you gave me in the hospital when I exited your body with mine; with my brand-new cheeks that looked just like yours. They still do.

We didn’t grow up religious. You were forced into the hands of Catholicism by your parents, but we never spoke of God or believing in forces greater than us. When we attended the funerals of your parents, I was a teenager but old enough to recognise the wedges that they had squeezed between you and your siblings. The spaces your mother had carved out into all seven of you with her brittle hands and veins that housed anger that she did not know where to place. She put some into each of you and your father looked away. We didn’t grow up religious but that day in the church when we saw Pa’s open casket you screamed bloody murder in the pews, and I saw you bigger than you ever had been. I was terrified I’d interrupt the rhetorics you howled toward a god I’m still not certain you believe in as you tripled in size. Afraid to approach you with the juvenile wisdom you had forced to exist inside of me, because I was a teenager; wise enough to know better.

“Mothers don’t ask their daughter to carry their hurt. To live for them.”

You used to utter words to us – your daughters – about being made to be our Mother as though a greater force (the ones we never discussed) willed it into existence, willed us into existence. About the love that consumed you. How one day we’d be mothers too and we’d finally understand how large the human heart can grow. But I got deeper into my twenties and decided I didn’t want to be a mother and you didn’t understand it. Didn’t know how it felt to long for a separate identity outside of the only ones that you were offered. Mother, wife, giver of life. You couldn’t understand that my fate was to turn monsters into people who did not fear their reflection, to quiet walls, to shed the mother-tongue of our house. That until I do, I do not have what it takes. Uncertain as I am, that there are enough days in this lifetime to offer to myself.

Unsure if I spend them wisely as I am on my own. If I round up, I am one third through my life. A blink. A breath. A butterfly’s wings flapped. Sliding doors. Screaming walls.

There is so much I want to tell you, Mum. You are still my Mother, the giver of my life, though it is the one I do not owe you. I see you in so many spaces; in the etchings of my DNA, the passages of time marked into my face, the hospital corners I fold into my sheets each week the way you taught me because you would not still your hands. I see you in my own, in the blue veins that will not house rage like your mothers, in the fingers that I am using to tear your past open. The fingers that I am using to tell our story so that the mother- tongue of silence can learn to scream the way that I do for you every day, with every fibre of my being. I wonder sometimes if we’d gotten it right in our past lives. Stuck to the right scripts, refusing to trade hats, places, roles, dialogue. We would not have played mother and daughter. Perhaps the gods previously had mercy we have not been privy to in this lifetime. The one that I am using to pull at the corners of the carpet with the hurt of our descendants buried underneath. I am hushing the walls and we are both still here mum, and there is still time to birth a new language; screams that will be heard. And if we don’t get it right there is always the next lifetime, where the pain won’t be buried in bones and live in veins and travel through blood because I halted it in its tracks and it faced me and it demanded to be felt.

About the author, Tori Watts:

Based in Kaurna Land (Adelaide), Tori Watts is 28 years old and has been writing for half of her life. She records moments of pain and pleasure in privacy as a means for exploring experiences. She worked in various industries, and is currently studying a writing and publishing degree. She has a strong penchant for matters of social justice, for learning and for faith in forces greater than us.

Find out more about the 'RUSSH' Literary Showcase.

This project has been made possible by CHANEL.

CHANEL is committed to continuing the artistic patronage initiated by Gabrielle Chanel. Gabrielle Chanel was never without books. They added to her life; they filled her life. It was from literature that she undoubtedly drew the strength to accomplish her work as a designer. It was literature that undoubtedly drove her to invent an allure that is eternal yet inscribed in perpetual modernity.