Where does one even begin with an introduction to Tame Impala? It doesn’t really seem necessary; yet Kevin Parker’s career trajectory is so unique; it seems inevitable. From Myspace demos that led to a signing with Modular for their album debut, Innerspeaker, a distinct voice in Australian music was emerging, a voice with such influence that it saw 2012’s album Lonerism consolidating it into a sound and a scene. Currents (which celebrates its 10-year anniversary this year) defined the sound of an Australian summer, cementing Kevin Parker as a singular song writer with mass appeal, leading to collaborations with Mark Ronson, Rhianna, Dua Lipa and Justice. It is these paradoxical pulls between obscure underground psychedelia and contemporary pop, introversion and extroversion and meaning and interpretation that have seen Parker play a pivotal role in the musical landscape of the last decade.

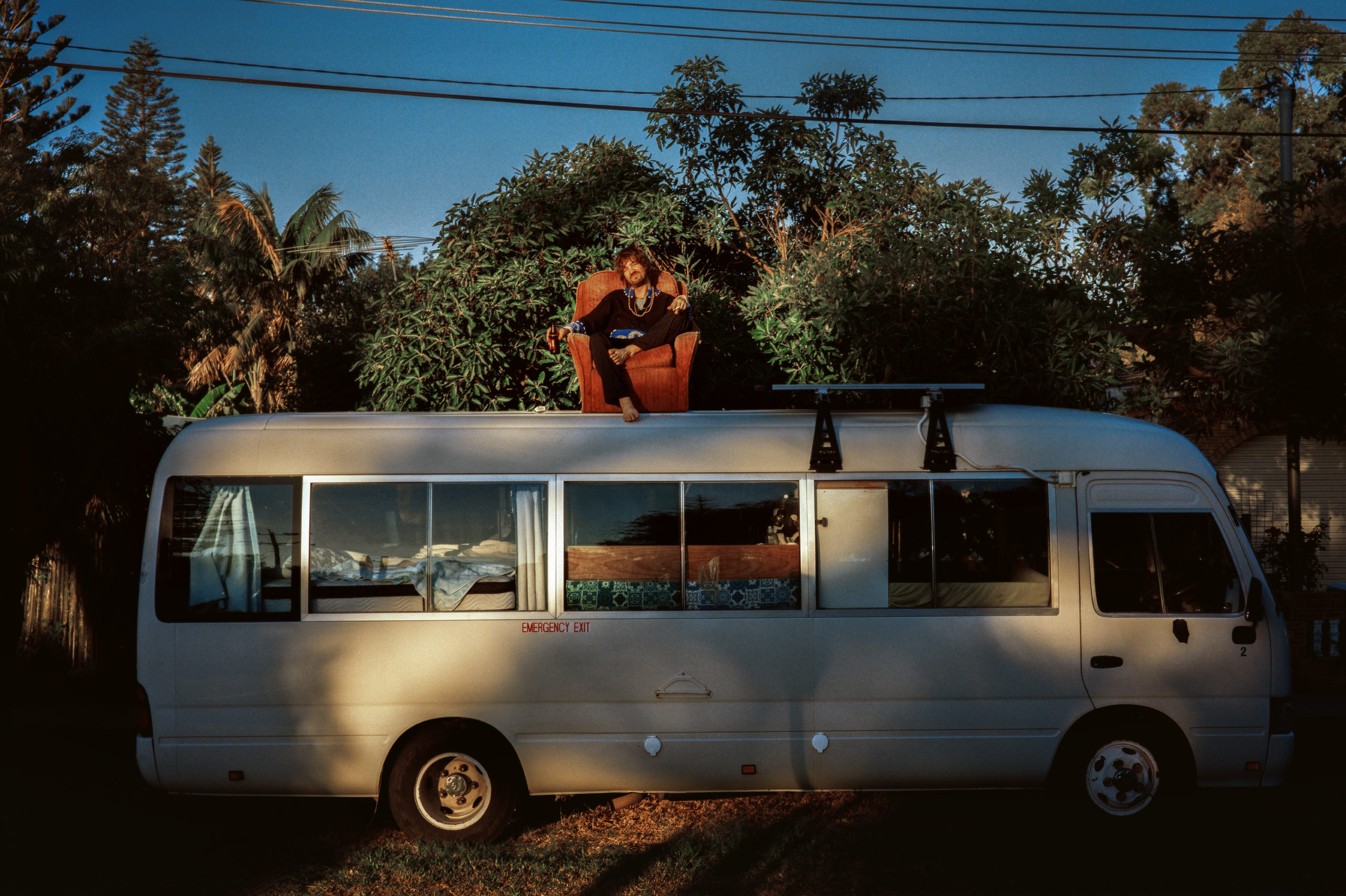

When calling an artist of such stature, you never really know where they are going to be: hotels, bars, desert retreats… so although I couldn’t have predicted it, when Parker and I speak he is in a small town called Lititz in Pennsylvania, which is the perfect backdrop for the call. It’s a remote town surrounded by Amish farmland and warehouses that, in Parker’s own words, look like “NASA for rehearsals.” These isolated hangers are where Parker will be planning his next live show and excitedly playing with lasers.

Both of us are in casual repose, calling from beds on the other side of the globe, which immediately allows for some relaxed intimacy; keeping it “casual.” Parker explains the perfection of Lititz for rehearsals: “It’s this massive pre-production facility in the middle of nowhere. You just have no distractions. They give you these arenas without any seats, and you build your whole show.”

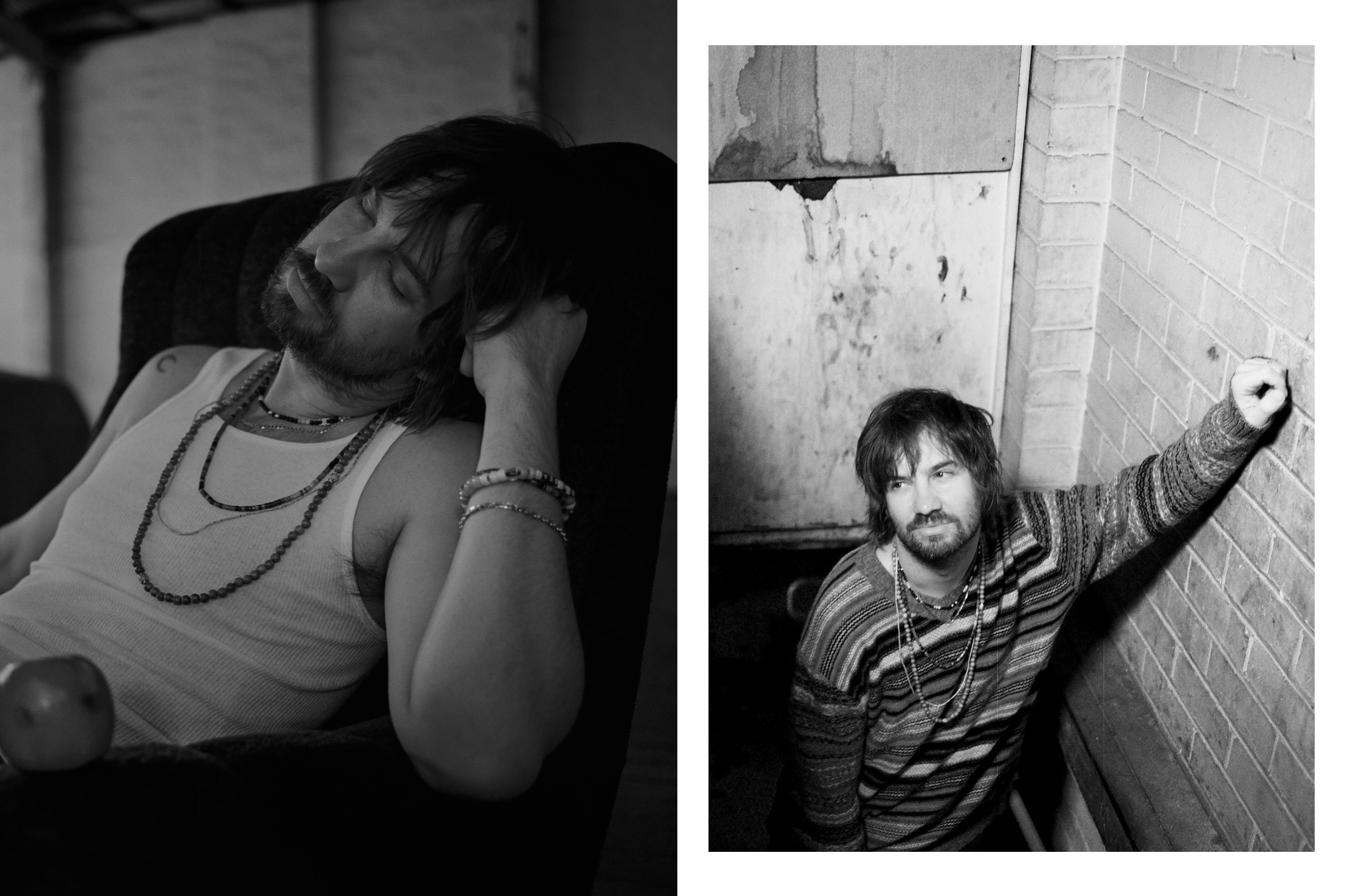

"I was trying to make a more human, more exposed album. I suddenly realised that I hadn’t been exposed enough in my music before. I’ve always made things so dense, so full, that I ended up hiding myself."

It could be considered a definitive visual metaphor for Parker, who so famously has worked on his work solo in bedrooms, to be planning his show in a barren stadium. “I love it,” he says. “There are no distractions. You just… disappear into it.”

One only has to read album titles or listen to the most entry-level of Parker’s work to know that isolation is a subject Parker knows intimately. For many, the mythology of Tame Impala has centred on one man and his endless pursuit of sound, meticulously, and with luck and genius coaxing hits out of a reverb pedal.

“Yeah, isolation helps,” Parker admits, “but I also get inspired by the opposite: being among the chaos. For me, writing music happens both when I’m in my happy place and when I’m somewhere I want to get out of. Music can be this escape thing, or it can also be something that comes to you when you're in your own blissful place. So, I like to think that I can embrace both ends of the spectrum.”

It’s that oscillation between extremes that can be heard lyrically on his latest, newly released album Deadbeat, where we hear Parker running from late night parties to return to himself. The record feels like both release and reckoning. It opens with the intimacy of an iPhone recording to feel as though you are in the room with Parker, before throwing you into the spiritual rave-high of a track like Ethereal Connection.

“I guess that’s what I’ve always been chasing,” he says. “Something that lives between those states.” I shan’t commit to the page my ambitious philosophical comparisons to Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil, but needless to say, we agreed there is a need for tension. “There’s always got to be a counterpoint.”

Deadbeat is the sound of Parker finally allowing that sonic “counterpoint” of his earlier records to take the lead. It’s as though a love of dance music and rave culture, which seemed so paradoxically unfitting for a ‘rock’ musician and subsequently repressed, has broken free and been allowed the reins. Whilst some fans may be yearning for some magical Guitar Hero moments, the human elements of Parker’s song writing become more prevalent, with more direct lyrics sitting higher in the mix, less buried.

On his “secret fascination” with dance music, Parker explains: “It’s always been a love of mine, even before it was obvious, even before it was imaginable that I could make that kind of music. It was a guilty pleasure for so long. I came from the rock world, you know, where anything that wasn’t guitar-based was ‘less than’, you know? So yeah, this time I just thought, fuck it.”

Laughing at his bluntness, he concludes, “it was a YOLO moment, for sure.”

“[Dance music] has always been a love of mine, even before it was obvious, even before it was imaginable that I could make that kind of music. It was a guilty pleasure for so long.”

What perhaps was more challenging for Parker was not the decision to press ‘go’ on the new direction but how to learn to do it. “It's quite challenging for me, because I can play all the instruments, but making techno music that actually sounds like great techno music is another thing entirely.”

The ‘shape’ of dance seems like a great way to explain the trajectory of feeling you might want to conjure on the dance floor, and I’m curious to know if there are any songs that synesthetically inspired Parker with this record. Sadly, I’m met with the “too many to name” response, but he does mention fans of the album should remain indebted to the Chemical Brothers.

Although imbued with negative connotations, Deadbeat “was just a word I’d written down in a notebook,” Parker tells me as I try to penetrate the DNA of the title.

“I stumbled across it weeks later and had no idea why I’d written it.” Rather than chase a title, Parker remains on the lookout, vigilantly, often not considering the dictionary definition, which although seems counterintuitive, aids the search.

“It just spoke to me. It felt perfect, despite the negative connotations. Someone disconnected. Someone lost. When I realised how many of the songs carried that energy, it just… fit.” I ask whether he thought about the irony of naming such a rhythmically rich album Deadbeat. “Oh, definitely,” he laughs. “That was the clincher. The word ‘beat’ being right there. It felt right, like drawing a circle around everything. A word that holds the chaos together.”

Just as there is the perpetual need for counterpoints, there is liberation through inversion for much of Parker’s language. “I’ve always used negative words as a kind of liberation,” he says. “It’s both. It’s releasing those parts of yourself, and it’s subverting the connotation. Once you say it out loud, it’s not scary anymore. You know that freedom you get from the feeling of knowing that everyone knows? That something is out in the open? Now I don't have to keep hiding. I don’t have to try to overcompensate or whatever. It’s also trying to put a spin on it, like taking a word like ‘deadbeat’ and glorifying it in a way, which is also kind of empowering.”

However, the record opens with a different kind of vulnerability. The first sounds of Deadbeat are not the shape of great techno but a voice memo Parker singing alone into his phone, the room noise engulfing him. “I make a lot of voice memos,” he says. “I was listening to them in the car one day and realised how intimate they are. They’re not recorded well, just a shitty iPhone mic. It just seemed like the exact thing I was after, which was trying to make a more human, more exposed album. I suddenly realised that I hadn’t been exposed enough in my music before. I’ve always made things so dense, so full, that I ended up hiding myself.”

Anyone who has made home demos has to fight the urge to bury vocals under lines of unnecessary guitar, synth or pads, and it’s easy to hide within textures. “You can forget how important it is to have a voice and write words,” Parker tells me: “you can fall prey to your insecurities.”

“I feel like some lyrics I have to pace around the house for days and months just to squeeze them out. But sometimes words just fall out of you and into the song.”

We conclude that in order to write this way, it is an exercise in restraint. That restraint, Parker says, was partly learned from collaboration. “Working with other artists opened my eyes to how powerful a voice can be,” not just physically or as a sound, but as presence and as identity.

Perhaps due to his origins in Western Australia, Parker’s writing process seems almost tidal, sometimes effortless, sometimes endless. “I feel like some lyrics I have to pace around the house for days and months just to squeeze them out. But sometimes words just fall out of you into the song. No Reply was a case where it was just so easy to write. One line after another came so easily because I was speaking from the heart. I'm also speaking from a part of me that I don't really voice often. The lyrics are meaningful, but they're also kind of playful, and yeah, kind of mundane.”

It is reassuring that there are flurries of work and famines in someone so respected, so I’m curious to know if there is a way of getting out of those less fruitful periods. Parker explains, “that's one of the most rollercoaster-like elements. Some days you feel like Nick Cave, and sometimes you feel like… not Nick Cave. Sometimes you feel like everything that you say is profound, and sometimes you just feel like you've got nothing to give.”

The remedy, as with many things, is time. “I just step away. Your own mood isn’t something that is very easy to control. You come back when it’s ready.”

One of the many tensions for Parker during the writing process appears to be the anxiety of making this record something earnest and new, and the fear of not being able to make it at all. “Anxiety has always been a key element in the process of my music. So, it's just a matter of wrestling with the beast – or you know what an even better metaphor is? It’s sort of like trying to ride the serpent.”

Part of the anxieties that plague musicians is sacrificing a record that’s personal to the masses, and for an artist so revered as Parker, it surprises me that that he still reads his YouTube comments. “It’s weird these days. Depending on which pocket of the internet you look at, you’ll find completely different reactions. I’ll go on YouTube or Instagram, and there’ll be so much positivity, but I’ll still scroll until I find the negative ones. We all do it, right?

“It's this baby that you've been growing for a year, two years, this thing that you've stressed and cried and laughed over – and danced to yourself, and loved, and hated. This thing you’ve had following you around for so long, and then it's suddenly seeing the light of day and being shared with the world. It's just such an overwhelming idea, you know? The idea of these songs that were once yours, and now are not yours; they belong to the world now. That transition weighs quite heavy on the artist, I think. Sometimes it even feels a little violating.” Parker laughs as if to soften the word, then lets it stand. “Because they were yours, and now they’re not.”

That feeling, he says, returns every album cycle. “When Currents came out, I remember reading this review saying the transition I made wasn’t working — that I should stick to what I did before.” I posit the idea that he, too, has been accused of committing ‘genre-cide’ although Parker felt like we had moved on from that as a society some ten years ago. “It made me laugh. People talk about genre like it’s a prison sentence. I thought we’d moved past that. But people love boxes. That’s fine. It’s human. You just can’t make art from fear of disappointing people. Every new thing you do will scare someone, you know, including yourself.”

“It's just this baby that you've been growing for a year, two years, this thing that you've stressed and cried and laughed over – and danced to yourself, and loved, and hated. This thing you’ve had following you around for so long, and then it's suddenly seeing the light of day and being shared with the world. It's just such an overwhelming idea, you know? The idea of these songs that were once yours and now are not yours; they belong to the world now. That transition weighs quite heavy on the artist, I think. Sometimes it even feels a little violating.”

If Deadbeat is an act of unmasking, its cover image complicates that narrative: a photograph of Parker with his daughter, Peach. “Honestly, putting her on the cover was probably the most misleading thing I could have done,” he says, smiling. “People see the word Deadbeat and a picture of me and my kid and think, oh, I get it — ‘deadbeat dad’. But that wasn’t it at all. It was just personal. Just… human.” Peach’s role is not in contextualising the title, but more a testament to Parker’s artistic practice. “Sometimes art is just putting things together and letting them mean what they mean. I can’t explain why that photo and that title work together: they just do. To me, it was about saying: here I am. This is me.”

The process feels simple, but it’s radical in its own way. After years of sculpting grand, kaleidoscopic soundscapes with imagery by Lief Podhajsky or Robert Beatty, the decision to give an intimate moment with his daughter adds significant weight, and allows us deeper insight into Parker as a person. The porthole into Parker on this record is one that is defined by connection. “I think Deadbeat is about connection,” he says. “Or maybe the struggle to connect. With yourself, with others, with reality. I wanted it to sound human, exposed. I realised I’d never really done that before.”

Returning to our NASA music station, Parker is preparing to DJ in support of Justice. “DJing is a real rush for me. When you're in a band, you’re just one of the guys. It's not all resting on you. Even though people see DJing as quite easy, there’s a responsibility that you have to keep the music going and to make it immense. There's a lot riding on it, which is why it's such a thrill. I love it so much. I love how nervous it makes me.”

But does Parker meticulously plan his sets? “I always want to,” he admits. “My dream is to have it all mapped out [...] but I always run out of time. Every set I’ve ever done, even the ones recorded for YouTube, I’ve winged it. That’s the best way. You don’t sound like the world’s best DJ when you do that, but it’s real.”

Naturally, if the love of dance music was hidden, was the love of DJing? Did he ever steal the aux cord at a party? Apparently, he tells me, only occasionally to play Outkast: “whatever had the most overlap with other peoples’ tastes. I wasn’t really into dancing myself for a long time.”

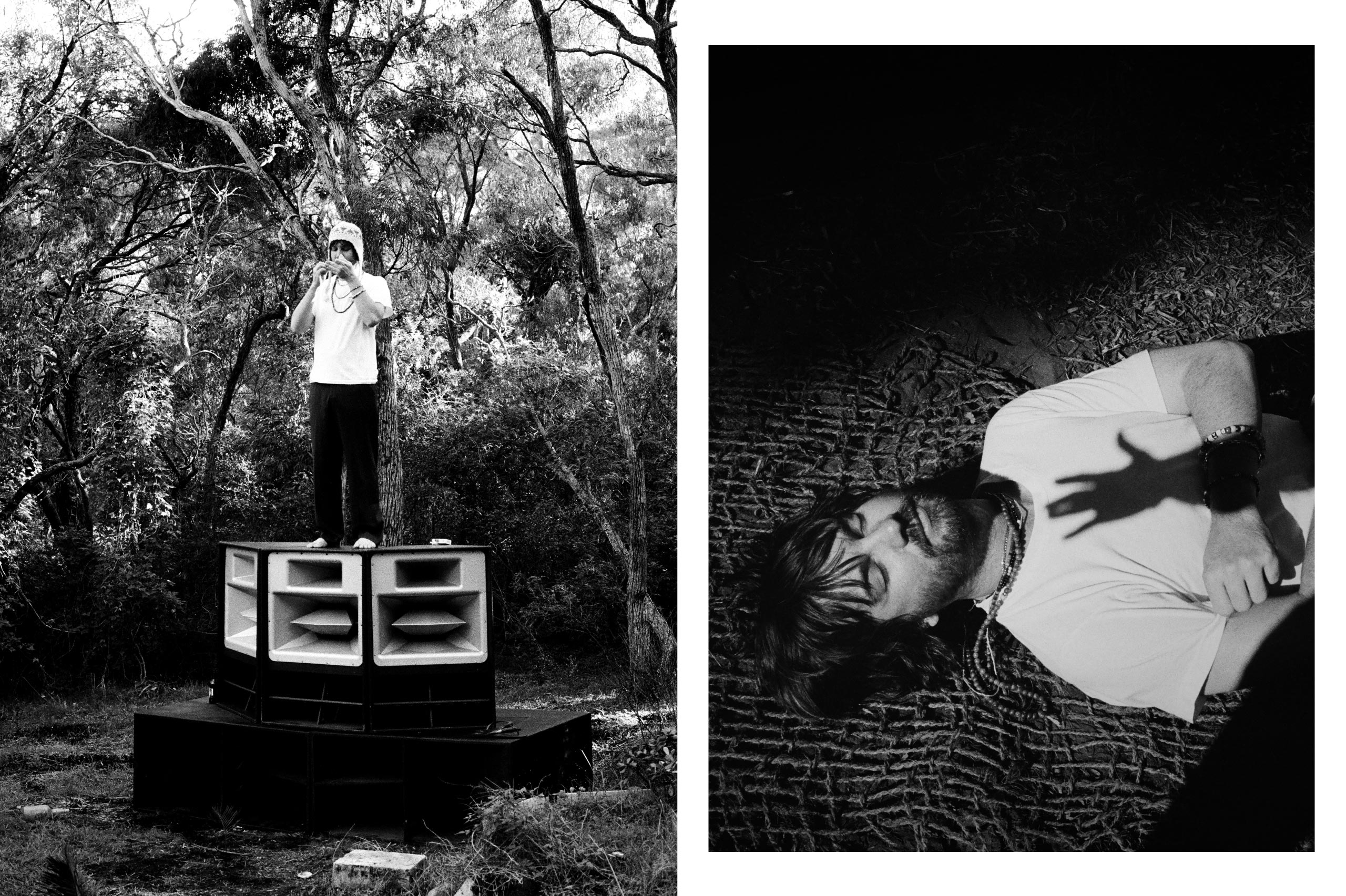

We have a brief tangent on the spirituality of bush-doofs and what within their nature makes them inherently Australian, rather than the experience being defined by landscape. Parker believes there to be something innate within the personality of them. However, before I can ask of future plans or about whether the string sound in Piece of Heaven is an Orinoco Flow reference, or the choir at the start of Dracula a deep Gothic Sisters of Mercy reference, we’re asked (politely) to wrap it up.

Parker reveals, accepts, liberates and challenges his sound, voice and persona on Deadbeat, and ultimately battles a dual-faced anxiety for connection. It is a record that champions a new voice for an artist who listeners perhaps thought they knew, but now they can see.

You can stream Deadbeat now on all streaming platforms, or catch him live supporting Justice on their Australian tour from 3-7 December.