In the same way a heartfelt text chain at 4am or entering someone's childhood bedroom can tether you to a person, visiting an artist's studio kindles an immediate sense of intimacy. As was the case when I entered Jedda-Daisy Culley's studio through a back alley in Alexandria.

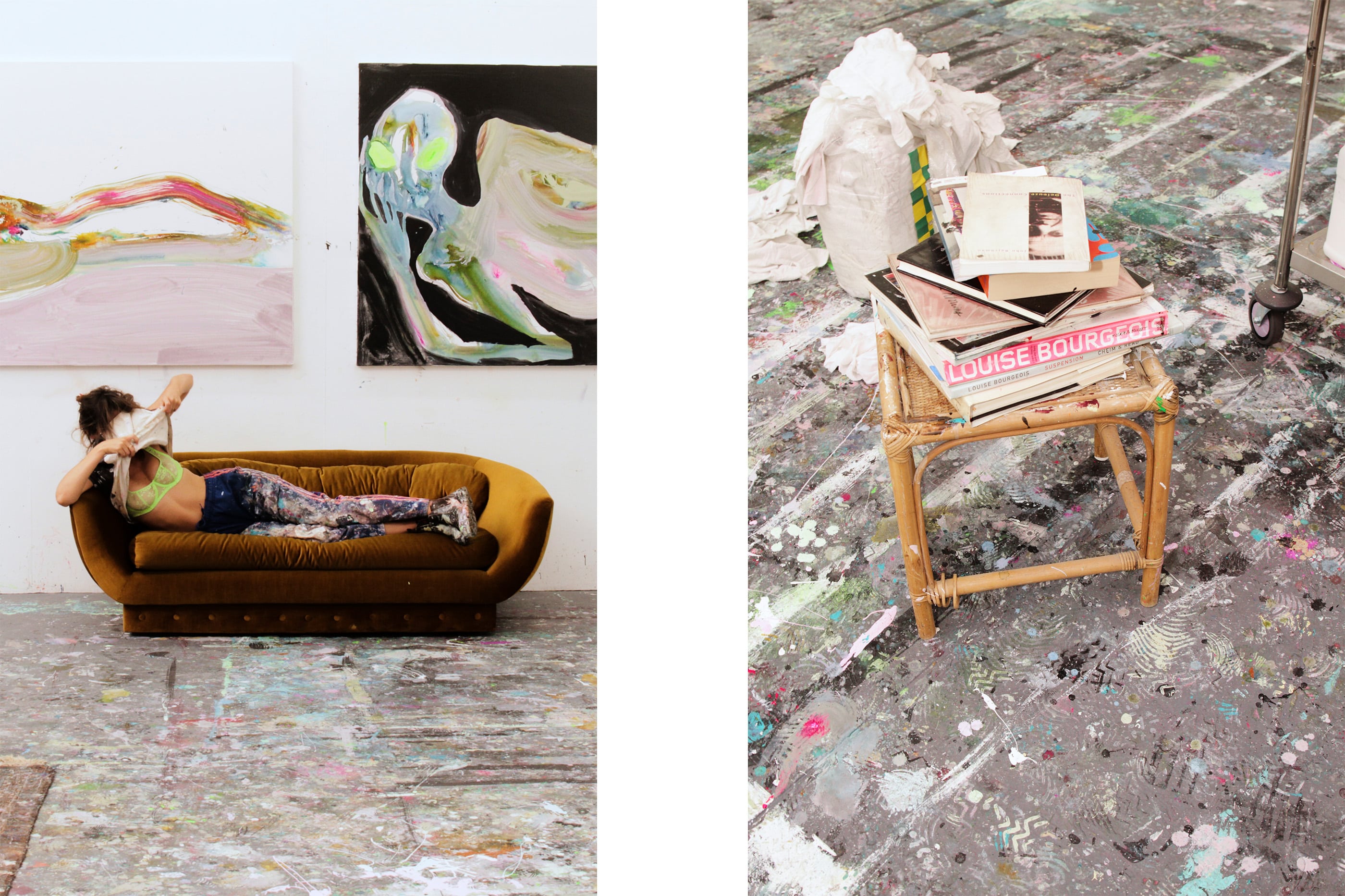

She greets me with a hug and a choice of three different baked goods ("in case you had any dietaries"). I opt for a Portuguese tart and we take our tea to the lounge area of the warehouse space – designated so with a rug and a burnt orange sofa. It's warm inside, in the same way I like to imagine an incubator is, and nearby there's a Vivienne Westwood box where sage sticks and a lighter lives "in case anyone I don't like comes in," she tells me conspiratorially. It's cosy and comfortable – a far cry from the story that inspired Culley's latest body of work.

On February 11, Jedda-Daisy Culley will present her fifth solo show and her first at Yavuz Gallery, Sydney. All around, the painter's artworks lay horizontal staring at us with their alien heads and oversized bodies jammed against the very edges of the canvas. Culley has been working on Unbodied for a period of eight months and the series continues where her last show and your mothers psychic spaghetti river left off. Both bodies of work are in response to a traumatic accident during the floods in March 2021, where the artist and her two children were caught in a rescue boat mission gone wrong on the Colo River.

Where the last series focused on the safety in domesticity, Unbodied interrogates the out of body experience that followed the near drowning. "This time around instead of turning the lens on the people who failed me" as Culley did with her 2022 series Download Hats, "I'm turning it back on myself and seeing how I was feeling at that time," Culley says.

"Having your adrenals running on overdrive for months afterwards, I honestly felt like I was like three storeys high. Someone would do something to make me feel uncomfortable and I just turned on them like 'woof!'"

"I think what I was trying to play with here with these paintings was the question of, is that a spiritual experience? Or is it just a chemical imbalance in the brain? I think it's the latter," she confesses. Eventually, it got to the point where Culley realised she could no longer live in this inflated, alien state. "Not only was it physically exhausting but it wasn't very social to be constantly ready to attack," she says.

"So I thought, how do you squish yourself back inside yourself? Because I really did feel huge."

Jedda explains how every body of work usually begins with a lot of writing. At first, it's a way to take the temperature of how she's feeling. Then she'll start painting and once she's finished, she'll return to the block of writing and pull out phrases and words to be massaged into titles. "It took a little while to get to this title. It's always hard to find a title that's short and embodies everything you want to say. This time I have really long titles for each work but I wanted the title for the show to be simple" – hence Unbodied.

Her approach looks a lot different for Unbodied too. "I came up with calling my paintings 'psychoactive portraiture'. If you Google that on the internet, it just says you're painting while on drugs. But it's not what I mean."

Rather, Culley would paint in six hour stints in an attempt to tap into the pressurised state her mind was trapped in following the accident. "I'd have to almost psych myself up into a very – not hostile, but active state where I'm remembering. It's exhausting," she admits. "But that's why it has to be quick. You can't stay there for too long otherwise it's unhealthy."

For this reason, there's a sense of urgency to the Unbodied paintings. Loose, furious strokes recreate the repose from classical paintings. Culley wanted to make paintings almost uncomfortably fast. "I had only one chance to make it work, which is kind of what happened to us. You don't have the privilege to sit back and consider if you're making the right decision. It has to be right otherwise you're going to die... which is such a hardcore thing to say."

Jedda explains how she found the repetition in Unbodied important. It's something she recognises and admires in the work of American artist Josh Smith. "I think when you're going through a therapeutic process, to repeat something really just helps to either make that connection or undo that connection."

As for the energetic palette present throughout her works? Culley explains that "colour is something that's so natural to me. It doesn't matter. Even if one day I'm like 'alright, Jedda enough. You're gonna just do a green and orange painting because you should just pare it back' it still comes back in," she laughs.

Throughout the process of creating Unbodied, Culley was compulsively consuming a lot of other art as well. "I like to be in constant heartbreak when I'm painting," she jokes. "I want to be swelling in a sea of emotions." It makes sense then that she cites Magnetic Fields along with Townes Van Zandt, Blaze Foley, Bruce Springsteen and Lucinda Williams as the musicians on loop. "I'm the kind of person who obsesses over things, I will listen to a song on repeat and burn it into the ground and it will never get another play."

As for books, Susan Sontag's Illness As A Metaphor brought a lot of clarity. "That feeling of being unbodied is addictive," she tells me and Sontag speaks to it. "It's a place where you feel connected to both life and death. A place where living feels exhilarating." Straight after the accident Culley recounts how the disconnection from her body meant she would take greater risks like walking into traffic – not because she wished to cause herself harm, but because she didn't think she could be harmed. "I was almost living on another plane," she says.

Things are different now, though. "I definitely lost a lot of courage on a daily basis. I used to be very adventurous and jump off cliffs and swim in giant waves," Culley says. Jedda has become hyper-vigilant since the accident. "I never used to be a neurotic flyer but now I am." When she starts her car engine she leaves the door open just in case it explodes and she needs to escape. If she's driving over the Sydney Harbour Bridge all the windows have to be rolled down in the unlikely event that she plummets into the water below.

"It's just a part of me and I've just decided it's okay. I think sometimes you've just gotta make peace with stuff. I might go grey faster than other people but that's fine. I do meditate a lot," she assures me when I let out a moan.

The experience of putting Unbodied together has also taught Jedda-Daisy Culley to value the duality that comes with being a mother. "It's okay to tap into being huge. Especially as a woman, you know? Growing up you're made to feel like you need to be, not necessarily submissive, but not the loudest voice in the room or not be the most powerful one in the family dynamic. Being a mother there's that pressure to be extra gentle, extra soft and nurturing – and you do, but there's another side to it where you need to be extremely powerful. It's taken me an embarrassing long time to be okay with that."

Unbodied by Jedda-Daisy Culley opens at Yavuz Gallery on February 11.