“Time runs in, and then runs out …” – Townes Van Zandt

The way watercolours bleed out, softer and paler, losing themselves at the centre, receding gently to disappearance. The way human skin turns inky against a vast darkening sky, a blotchy silhouette, and then nothing, all shadow lost. The way a tapestry, perpetually added to, over time grows larger than the sum of its threads and eventually envelopes everything. The way an idea stitched together by a bulging collective can weigh too heavily in the individual mind. The way a woman, beholden to biology, can feel reduced to the basic requisites of her function, and through the slow deletion of self, the erosion of nuance, the incremental melt of identity, she becomes only an entry point for life, a transmuter of data into matter. A portal and a printer.

“I almost stop breathing for a second when I realise I’m about to share this with the world. But did I already share it when I felt it?

I don’t know, but I am choosing not to hide.”

“They are blankets for gentle protest, for a softer approach when talking to ourselves and each other.”

As an artist and a mother, Jedda Daisy Culley has known the profound creative and transformative potential of experiencing herself as a vessel for life, a conduit for the manifestation of form. Her previous exhibition, Burns at the Lands Brim, explored her initiation into motherhood with the births of her two children, and the struggle of releasing long-held ideas and expectations around how that should look and feel. Her latest body of work is, in a way, also about letting go. Printing and Portals was birthed in lieu of a life that never was, from the unfathomable void of existence annulled – the hollow echo of an almost. Miscarriage is a loss that has no language. It is a lonely, disorientating grief of an emotional magnitude too often underestimated and scarcely understood. But for Culley it found its expression, and ultimately its transcendence, through the catharsis of art. “This body of work grew from a place of sorrow. I was processing loss. I was feeling it leave my body,” she explains. “My watercolours were like a map I drew. Navigating the way through. I felt like a portal for change. I saw an in and an out. Change is like life and death, there is a beginning and an end and there is always a newness that’s left behind. I let something go. I invited it in but then I chose to let it pass through me. This show is a self-portrait. It’s how I felt and how I saw myself at a vulnerable moment.”

Printing and Portals is a multi-disciplinary show – each medium, in its own capacity, tells a story of the inner tension and transformation of its maker, of her urge to hide but ultimate unwillingness to do so. “Watercolour is a gentle medium; it’s soft in its nature and its luminosity, it feels transient, like you can see through it,” she says. “I wanted to paint myself at this time as if this moment would pass but it will always be a stained memory. I also worked on them very privately, so they are small. I could keep them to myself and hide them inside a book if I felt they were too confronting.”

In contrast, her textile weaves are oppressively large and weighty, screaming contemporary aphorisms in overbearing font. ‘YOLO’ and ‘CALM’ are two concepts Culley found deeply agitating, particularly as a new mother, and represent the kind of meaningless motivational speak that effaces nuance and complexity from our emotional vocabulary. “[The weaves] were created with a repetition algorithm and talk of shitty printing and memes ... The idea of ‘carpe diem’ [seize the day] can create a fear of freedom; these works wonder how long a moment can be.” She goes on to say, “the process of weaving is slow, it’s meditative. I wanted to choose two overwhelming ideas to meditate on. Two giant themes that dominated my mind as a mother; the act is slow but the scale is huge. It’s like that moment when you feel the anxiety, that extreme vulnerability and you can’t go on for a second and then you have to. You have to keep weaving this gigantic idea that you can’t deal with.”

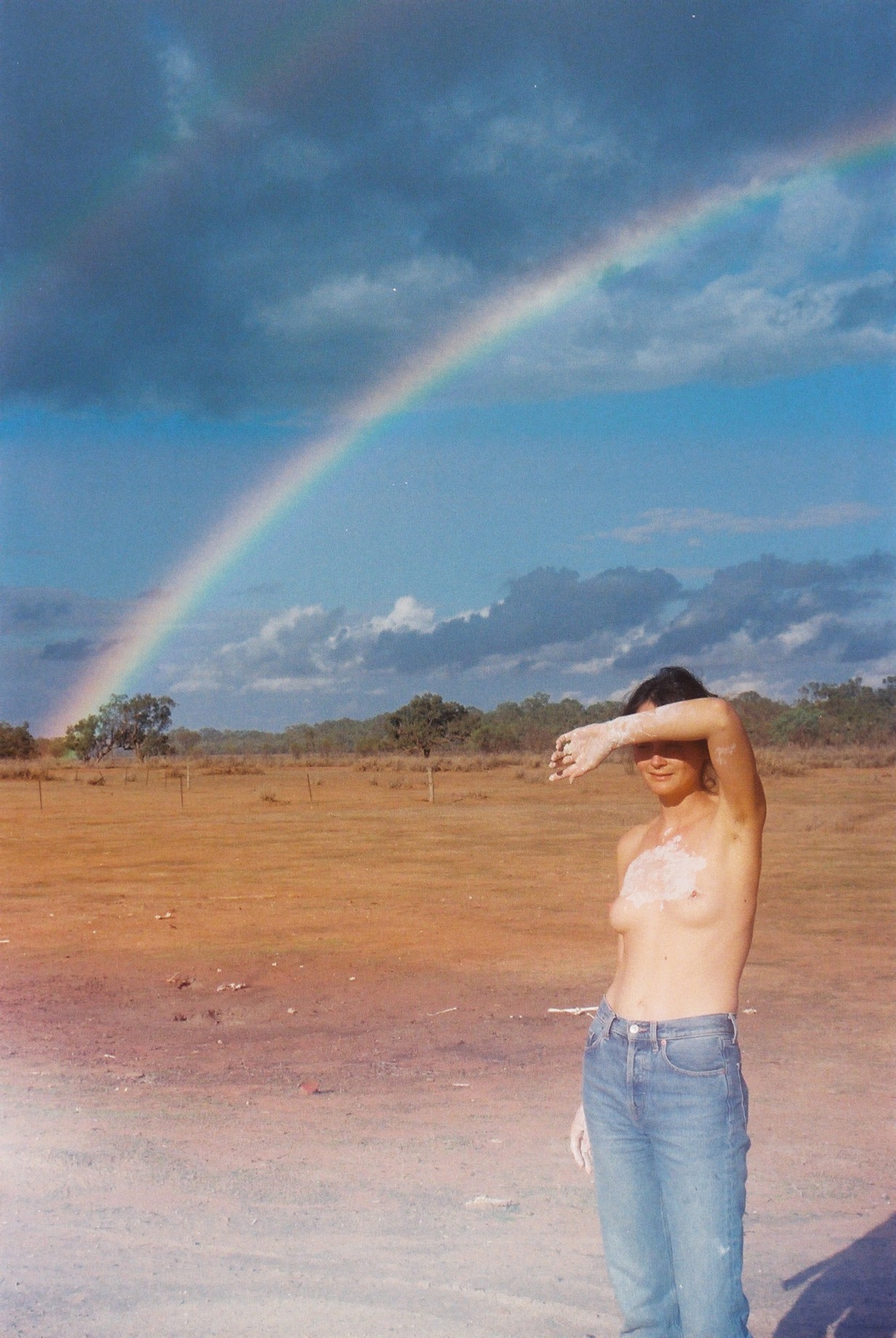

Her video work, which will be featured as a large format projection, is again representative of the overwhelm; feeling consumed by both cultural ideology and natural forces, and the artist’s reactive urge for disappearance. “The video work is a landscape painting. It’s me dissolving into the landscape, dissolving into the sky; a portal as I leave. As I choose that leaving is the strongest statement I can make. It’s all the same story, it’s all me, it’s just different forms for telling the same feeling.”

“It is a true expression of how I feel about myself in more ways than one; as a mother, a lover, an artist, the impossible task of loving yourself or another, or of painting a huge landscape, a huge sky full of all its history and subtleties.”

While Culley’s work centres on the female experience, weighted in themes of motherhood, birth, and feminine identity, the story she ultimately hopes to tell is a universal one. Loss, in all its manifestations, is a human experience. The awareness of transience and the ephemeral nature of life’s material form is an unsettling strangeness that underpins all of existence. A man, or a woman who isn’t technically a mother, may not know the visceral sensation of life leaving their physical body but that does not mean they don’t know, or won’t know, the mournful emptiness of its sudden withdrawal in one form or another. Culley’s intention with her work is always to pull together the threads of her deeply personal experiences and loop them into the broader narrative of humanity, so that the “feminine” becomes the human, the woman’s pain and transcendence of her pain becomes the collective pain and transcendence of all pain. “I feel that no matter how raw and confronting a women’s suffering can be, if it excludes or alienates others it will lose its potency. We are here together in this human experience, the message has to be universal if it’s going to be effective.”