Hayley Millar Baker grew up on rock ‘n’ roll. The type of soundtrack that blasts in your living room on a Saturday night when the coffee table transforms into a stage and the broom in the closet becomes a microphone. A sea of family rocking side to side as roars of laughter drowned out the noise in even the most testing of times. A sense of invincibility that makes you feel all grown up, perhaps even a little too soon.

Memories have always fascinated Millar Baker. In her world, they are fluid – constructive. Through her multimedia photographic works, she bends time and place, translating her personal experiences into shared narratives. Removing, refining and reworking layers to reveal the bare bones, leaving just enough space for her audience to inject themselves within the skeleton of memory.

Identity is at the centre of how we understand the human experience, and in Millar Baker’s work, we’re all on display. Incorporating the use of photography, collage, and film to interrogate and abstract autobiographical narratives and themes, her storytelling encourages us to embrace that the passage of identity, culture, and memory are not linear nor fixed.

Find strength in the moments in-between.

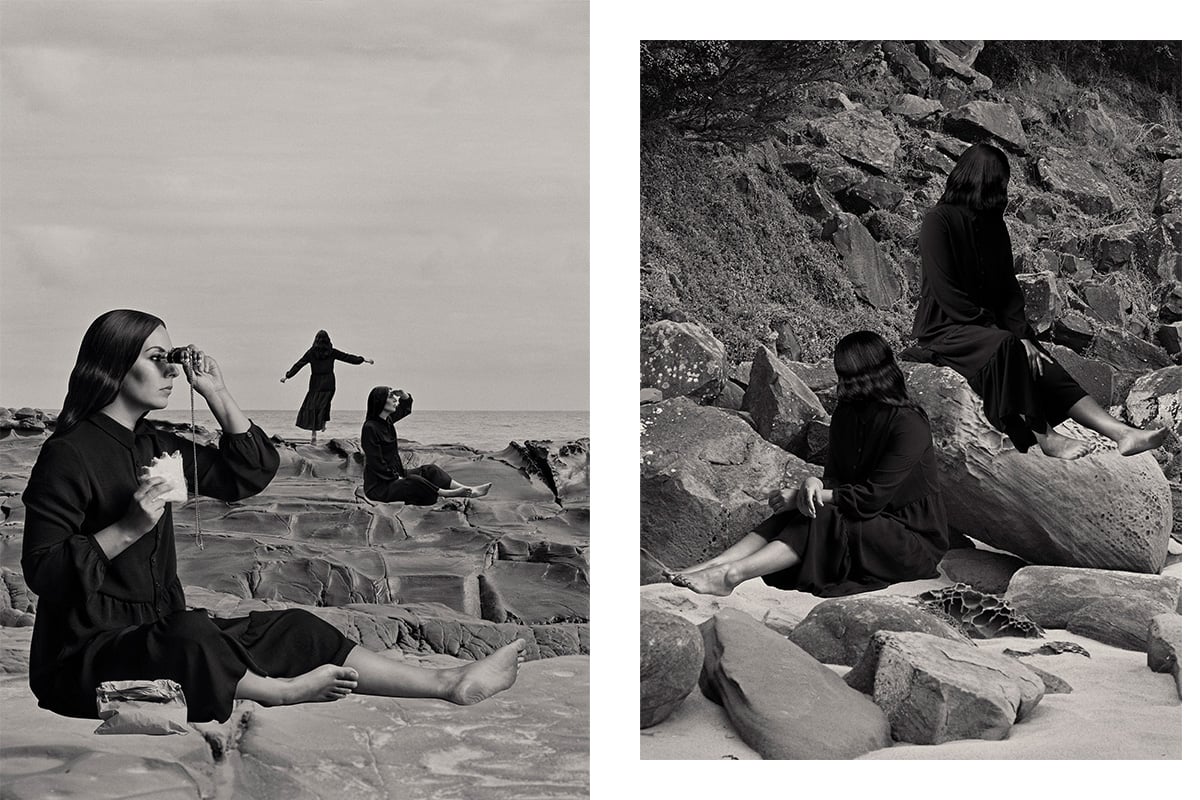

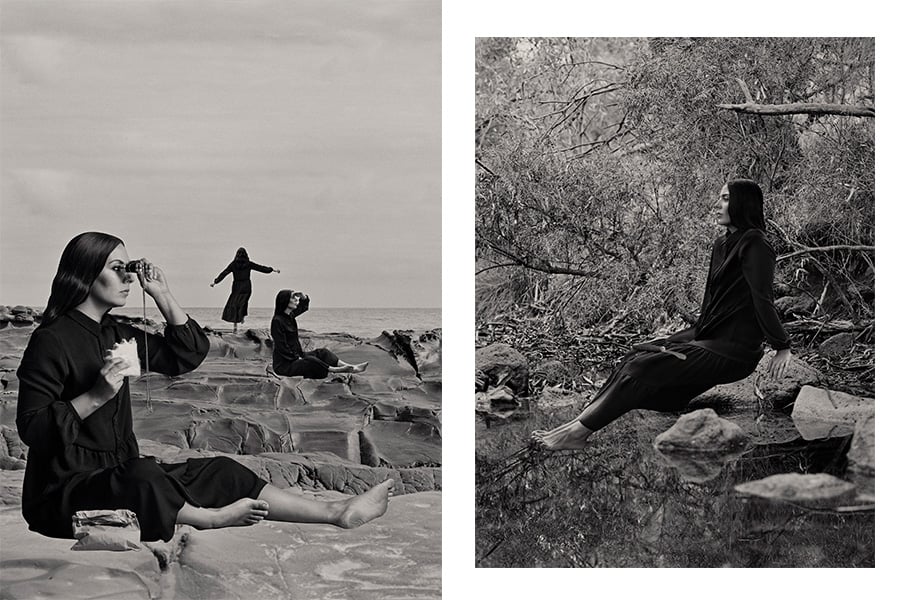

I Will Survive 5, 2020

Tell me about your childhood. What were some of the experiences that became sticking points?

My childhood was a wild adventure. I grew up on the outskirts of the Western Suburbs of Melbourne with my sister and cousins – think: Rob Reiner’s Stand By Me, but make it girl gang. We dealt with quite a few confronting and tragic deaths in our youth which led us to experimenting with séances (as seen in Nicole Kidman’s Practical Magic). I won’t say they worked, but I will say I haven’t had a quiet moment without spirits since. It was the four of us cousins most of the time, occasionally six. Our mothers, all sisters, were children at heart, very rock ‘n’ roll, very much dealing with their own scars while blasting the most stunning soundtracks – The Doors, Led Zeppelin, The Cure, Eric Burdon and The Animals, Credence Clearwater Revival, the list goes on. Growing up in the 90s was such a different vibe to the world today. We definitely thought we were invincible on our escapades, and I would say that’s credited to having ‘grown up’ a little too quickly under our parent’s roofs.

Your art is so heavily steeped in research. What does the process from research to creation look like for you?

My art practice is a total process start to finish. I tend to spend between six months to a year on research for a new project and that is simply so I can enter the creation period being fully aware of my intentions and ambition for the work. I definitely don’t like to rush my process. When I begin a project, I start with pinpointing a personal memory or story that coincides with the themes I want to centre, and then I strip it back, take it apart, abstract it, and morph it into a whole new being that can be read in a broader context. My research to creation process can be lengthy and intricate, but it’s also really fluid. I like to go with the flow and let my instincts guide the work. Every projects development is actually really organic and beautiful to watch unfold over time, and its outcome is always so evolved from its beginning.

Your work is rooted in the idea of connecting times and places, creating a non-linear exploration of past, present and future. Do you see the layered and repositioned treatment of imagery in your art as an extension of this?

I like the idea that memory is constructive, and time is fluid, so it makes sense for me to construct my images through processes of collage. Collage is the key element in my practice that I employ to illustrate these notions of memory and time. I like to purposefully remove the identification of a particular time or place, the details are not important in the narratives reading, so to leave the space open for interpretation. The great thing about using collage within photography is the way it’s so easily manipulated and if done in such a way, can be believable. Collage lets me bend time, create impossible narratives, and amplify flaws over multiple eras and places in a single image to reflect a memory and better tell my story.

Left: I Will Survive 1, 2020. Right: I Will Survive 8, 2020

You have spoken before about how human presence in your work is a representation of a character in a broader narrative rather than the individual experience. How do you separate the personal to create art that speaks to a shared memory or experience?

This is a really good question and something that I spend a lot of time thinking about. The foundations of my work will always be individual and that’s just because they’re birthed from my personal stories, but it’s really important for me to extend the character to reach a somewhat universal experience. Identity in storytelling is vital, of course. My experiences stem from my identity and belonging as an Aboriginal person, as a woman, where I’m from, and every other identifier personal to me. But the way I’ve learnt to separate the personal is to dismantle the memory or experience that I’m basing my work on. Pulling apart the nitty gritty flesh from an experience leaves its bare bones, and its bones are what helps me shape the character to represent a wider community and theme. At the end of the day, I am making work about me, but if I can extend that to bring others into my narrative as if it were relating or reflecting to a story of their own, what a wonderful way to connect.

Art is not without its barriers – especially when it takes on such a personal front. Where do you turn for nourishment and does creating art ever intertwine with self-care for you?

My husband is always on my case about art consuming me, being both my job and my hobby. There is no escaping it, not that I would ever want to anyway; I live and breathe to create. So yeah, I would say that art keeps me grounded and is an act of self-care for me. There have been times over the past two years of the pandemic where I haven’t been able to work and I can tell you that the inability to create and see art in real life was something else (and not a good time). Because my practice is really intricate and deep, I sometimes need my nourishment to be shallow like binge watching TV shows or movies where I don’t need to use my brain and can just switch off. I’m lucky that my art takes me all over the world but I’m never too far away from the places that revive and replenish me.

Your work focuses not just on redefining how stories are told, but why they are told. Do you find strength in reclaiming Indigenous history and narratives through the art you create?

I wouldn’t say I’m reclaiming Indigenous history through my art just because it wasn’t unclaimed – it’s always been ours and has always belonged to us regardless of whether the mainstream choose to learn or tell it. I definitely find strength in being confident in my identity and using my identity to explore specific perspectives of my understandings through the art I create. I descend from and belong to the Gunditjmara and Djabwurrung people and lands, which are beautiful, abundant, and magical. I am blessed to descend from my ancestors, my existence is a true miracle though (research the violent genocide and assimilation of Victorian Aboriginals), and I never take that for granted.

Do you ever think about your legacy – personal or creative?

Yes, I absolutely do think about what legacy I would leave behind. It’s a strange thing to think about and my mind always changes as I get caught up in different stages of my life and career. After a nice big growth period over the past two years, I’ve found myself at a point in my life where I purely want to embrace myself as an artist and person – honestly and truthfully just be who I am. My practice has evolved and refined quite a lot during this growth and I’m currently creating art that I feel truly represents me in my time and I’m really enjoying it. The way I’ve been looking at it is that there is no better person to tell my story than me, and no better time than now. The best creative legacy I could leave behind is art I’m proud to have created that can continue to live on beyond my existence. I’m also a mother of two, Maeve (four), and Quinn (one), so being a role model and nurturing them to become self-assured and self-reliant in their own lives is really important to me.

What can we expect to see from your work in 2022?

This year is going to be a really fulfilling year for me. I am premiering my first short film Nyctinasty at the National Gallery of Australia’s 4th National Indigenous Art Triennial from March 26 – July 31. I’m really proud of this work, it’s new ground for me and I’m excited for it to be released into the world! I’ve also started research for my second short film with production likely to happen later this year for a 2023 release. And lastly but very importantly, I have my early-career survey exhibition There we were all in one place touring Australia. The exhibition brings together my first five series of photographic work from 2016-2019 that examine Aboriginal experiences of time, memory, and place post-colonisation. The exhibition has been a really humbling way to wrap up that chapter of my practice as I enter into the next and continue to grow.

To experience the Lust issue in its entirety, the March edition of RUSSH will be available on newsstands from March 3 and through our shop. Find a stockist near you.

Feature Image: Left: I Will Survive 1, 2020. Right: I Will Survive 2, 2020

© Hayley Millar Baker, image courtesy of the artist and Vivien Anderson Gallery