Two summers ago, I found myself dining in Paris at the très un-European time of 6pm. The cause for such geriatric behaviour?

Trying to nab a table at Early June, the extremely popular no-reservation wine bar and restaurant near Canal St-Martin. There’s a tendency for natural wine bars serving small plates to falsely claim they “do things a bit differently here”. Yet for Early June , the assertion rings true. Since opening in 2019, they have been operating without a permanent chef, instead working with a rotation of travelling chefs from around the world, from Korea and Toronto to Amsterdam. When I visited, Swedish chef Joel Aronsson was passing through, putting his hometown spin on French classics, highlights included langoustine with nduja and fig tarte tatin. The food was delicious. The wines, ‘joyful’, as advertised. The hype checked out.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

We humans crave novelty, and if my pillaged savings account and camera roll are to be believed, I’m not immune. I love being immersed in the history of places while experiencing all the newness that comes with travelling: the food, the people, the culture, the sights and smells. Arriving in places that are wildly different to my everyday surroundings—be it a chaotic Bangkok street market or the shaded square of a Greek village—is a salve to the stagnancy I feel when stuck in the same place.

Life becomes infinitely more interesting when we’re exposed to new ways of thinking, hence the allure of chef residencies. Hosting diverse guest chefs introduces new voices and cooking styles to restaurants and guest houses, appealing to a broader audience that may not frequent such establishments otherwise. While hesitant to label chef residencies a trend, their surge in popularity is undeniable—a way to shake things up for chefs, owners and guests alike.

For Estonian-born, Paris-based chef and artist, Monika Varšavskaja (@cuhnja), the allure of chef residencies is the environments and freedom they offer. “The ones I’ve participated in have mostly been [at guest houses] in the countryside. Two perfect things are merged together: you have nature, and you have these really interesting people passing by to eat, or do a workshop. It’s the best of both worlds,” she says. “Most of the time, you are free to cook what you want to cook; to share your background, your culture, and the food of your childhood.”

View this post on Instagram

The transient nature of residencies, typically lasting from a few days to a month, resonates with Varšavskaja too. In contrast with previous generations, she belongs to a savvy Gen-Z and millennial cohort less inclined to bootlick and graft their way up the hierarchical ladder or spend 20+ years working for the same company. No less ambitious, these generations are more likely to find fulfilment in a pastiche of experiences that seamlessly blend work and personal life instead. “Chef residencies aren’t your ‘real’ life,” she says. “You know that at some point it’s going to end, so there’s less pressure, and you can move on to the next thing. Now, more than ever, we want to try a lot of different things.”

Despite her teenage obsession with cooking and hosting, Varšavskaja never aspired to work as a chef in the traditional sense. “I worked front-of-house and saw the exhaustion, the hours, the way the job becomes your life,” she says. “Running a restaurant, you also have to manage a lot of things—it’s not about food anymore, for you. I realised very early on this wasn’t the lifestyle I wanted.”

The culinary world benefits from such perspectives. Varšavskaja's work , buoyed by a desire to showcase her under-represented Estonian culinary heritage and informed by her background in art, is unparalleled. It’s sculptural, artistic, tasty. She’s drawn to working with others, most often her friend and longtime collaborator, Martin Planchaud , who she met at Domaine de Boisbuchet. The pair have since worked together on everything from catering a 100-person wedding (“without a dishwasher or kitchen help”) to a joint residency Numeroventi in Florence.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

“I clearly remember talking with Martin before going to Numeroventi, and we decided we weren’t going to cook Italian classics,” she says. “What’s the point when guests can have the better version in restaurants all over Florence?”

Instead, the duo turned locally-sourced produce into the 13th-century mediaeval feast of their dreams, with a giant pork shoulder, swords fashioned out of vegetables, chianti wine leaf dolmas, pirogi, cherries au sirop, ricotta al limone, and decorated pies typical of Eastern European cooking, served alongside “lots of dancing ”. The banquet was laid out on Numeroventi’s communal table with an 18th-century fresco as the backdrop. It was as much a feast for the eyes as anything else.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

“I mean, it was amazing,” Varšavskaja says, laughing, when I ask about her experience at Numeroventi. As if cooking inside a palatial 16th-century palazzo, where a Baroque statue of Hercules, perched atop a plinth once occupied by Michelangelo’s David, welcomes you in the lobby, could be anything but. “Being in that incredible space gave us so many opportunities to create something bigger than food,” she adds.

When I speak to Martin Planchaud, he’s nearing the end of a one-year residency at Villa Medici, where he’s combining seasonal ingredients with his expertise as a Paris-trained chef, instead of emulating local Roman culinary traditions. Standout memories include turning the villa’s grand salon into a giant classic train wagon restaurant for the opening dinner of the Orient Express exhibition, and “waking up to peacocks screaming in the house.”

A true craftsman, Planchaud sees value in both restaurant work and taking his tools on the road. “Working in fine dining brings knowledge and rigour to your skills, while travelling to places like Numeroventi allows more space for fun, free time and unexpected discoveries,” he explains.

Numeroventi’s first-ever guest chef was founder Martino di Napoli Rampolla’s 88-year-old grandma. The tastes and aromas of her cooking saturate his childhood memories, in particular the myriad ways she’d cook with their chickens, from liver crostini (“the best I’ve had anywhere”) to tortellini with chicken broth. In the summer of 2022, guests and visiting artists were treated to both her homestyle cooking and the chance to learn how to make pasta from a maestro. “She’s a real character,” Rampolla says, laughing. “I wouldn’t wish for any chef to meet her in the kitchen.”

View this post on Instagram

Since opening in 2016, the contemporary Renaissance guesthouse and artist residency has been a welcome alternative to the mass tourism that threatens to destroy Florence's charm. In a city where hordes of visitors often converge upon the same panini shop or take identical selfies on the Ponte Vecchio bridge, Numeroventi is a peaceful sanctuary—a place for artists to creatively recharge, and a way for Rampolla to give back to his city through events and exhibitions, like the forthcoming music residency program with Cyrus Goberville from Bourse de Commerce. Adding chef residencies into the mix was a natural evolution of this concept; an invaluable cultural, intellectual and creative exchange.

“I think it’s genius,” Rampolla says. “The chefs arrive, there’s a lot of excitement from them about being in Florence, discovering the local produce, making dinners, and inviting guests over. We share a life together for a week or a month, which is always super nice.”

George Wood-Weber, a Paris and Florence-based photographer who works on Numeroventi’s communications, agrees. “No day is ever the same and we really thrive on this,” she says. “Enabling chefs to come and work on special projects beyond the constraints of a typical restaurant creates such unique and beautiful settings. Our chefs inspire us both in the way we approach food and how we design and interact with the space.”

View this post on Instagram

She recalls a lunch hosted by Penelope Volinia, who, along with the team and some of the artists, foraged all her ingredients in the surrounding Tuscan countryside. “The dinner we had with Elena Petrossian from Ananas Ananas also saw us eating dessert with our hands off a floating table,” she says.

Australian chef, food stylist, and Numeroventi alumni, Sian Redgrave, sees residencies as the natural response to our capacious hunger for novelty. “They open opportunities to people from different cities, countries, and cultures, unveiling new ways of approaching our craft,” she reflects. “Shifting surroundings and being around new enthusiasm feeds the joy of collaboration… bringing innovation and curiosity to the forefront, and reinvigorating the reason we all love the industry we are in. Guests find this new energy exciting too.”

View this post on Instagram

Redgrave has also been embracing the burgeoning culture of residencies on her home turf. She recently worked in the kitchen of Melbourne's lively Florian, and is set to collaborate with Dom Gattermayr and Jules Blum at Julie, a hatted restaurant located in the historic Abbotsford Convent, as part of this year's Melbourne Food and Wine Festival lineup.

“A future project for me would be to combine my past studies in design and visual art with culinary practices at venues that offer artist residencies,” the self-described ‘restless creative’ says, citing Rae’s in Byron Bay and At The Above in Melbourne as two local establishments leading the charge.

Situated some 15,000 km away, the head chef of Grus Grus in Stockholm, Bill Allison , epitomises this new cadre of multidisciplinary chefs who see residencies as a way to bring together their talents—both in and out of the kitchen.

View this post on Instagram

During his tenure as head chef of Public Space in Amsterdam, Allison not only helped the business transition from a café into a restaurant, he also took their Instagram following from 5k to 14k. The man knows how to create hype. “I always say that I’m a brand. When you hire me you’re hiring more than a chef,” he says. “I have tons of creative ideas unrelated to food, like curating events with winemakers and chefs, menu structuring and layout, poster creation and playlist selection.”

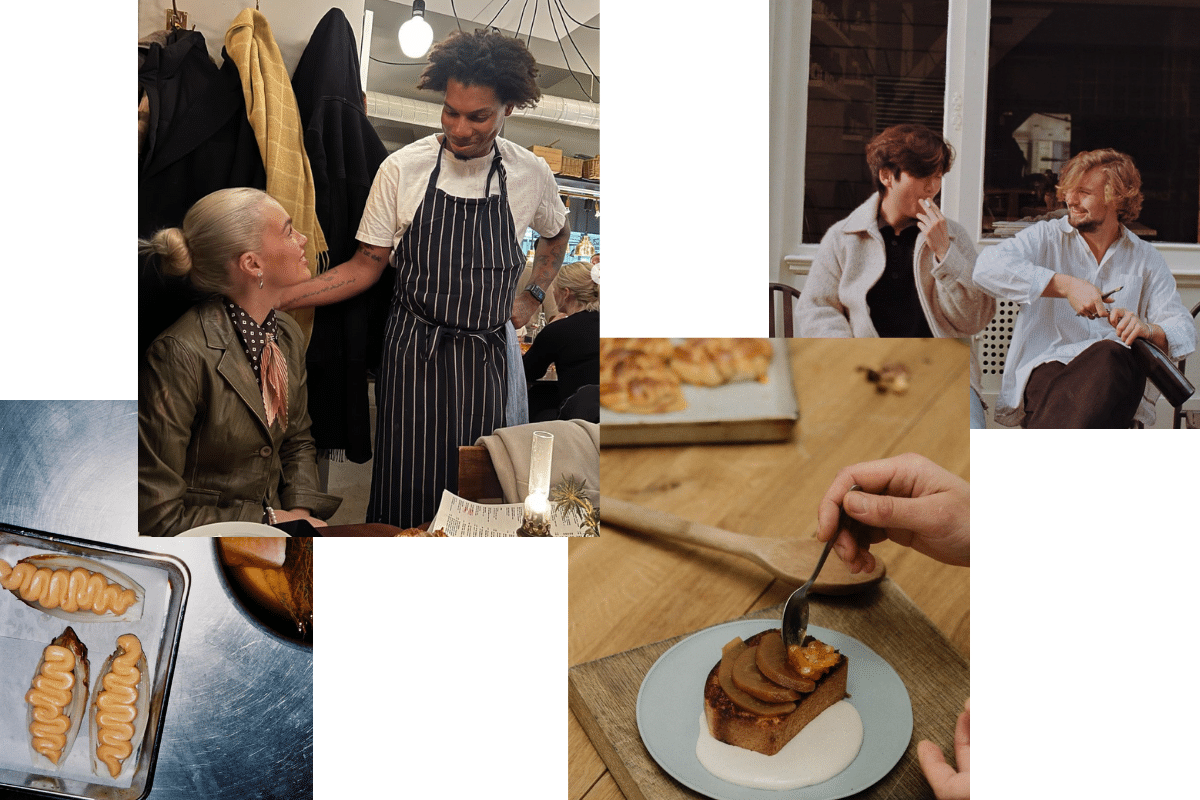

His first foray into chef residencies came in the form of a week-long pop-up at Early June in 2021, where he’s since returned. “I love it there,” he says. “They have a small, beautiful team of great humans. It was my first true taste of hospitality and what wine bar culture can be like.”

View this post on Instagram

These days, he’s been pouring his creative energy into Patois , a collaborative side project he started with his wife, sommelier Ebba Seppänen Allison . Through it, they combine her love of natural wine with his Jamaican culinary roots, and have popped up in kitchens around the world, from Bangkok’s Chenin Counter and JaJa in Berlin, to London’s 180.Corner and the Oakley Court hotel in Windsor. In general, he believes people love the exotic feeling of eating food from a travelling chef. “It’s like DJs bouncing to different clubs every night,” he says. “It’s cool to want to have something unique happening in your city and to be the place that orchestrated it… From a business and chef perspective you gain a new following, and from the diner perspective you get to eat a style of cooking you probably can’t get where you live.”

View this post on Instagram

In Mallorca, the guesthouse Casa Balandra has been drawing chefs, artists and in-the-know guests to the island’s tranquil shores since opening in 2020.

View this post on Instagram

Before transforming into the community-driven oasis it’s known as today, Casa Balandra started out as an intimate supper club that co-founders and sisters, Claudia and Isabella del Olmo, ran out of their kitchen in London. The dinners were inspired by the Spanish tradition of Sobremesa, whereby lingering at the table long after the dishes are cleared is considered just as important, if not more so, than the food itself. The sisters would encourage each of their six guests to invite a friend along. “We wanted to create a larger community of people… guests would arrive at 8pm and usually leave around 2am, after sitting at the table for hours, drinking wine and Hierbas, and chatting away,” Claudia del Olmo says.

As tends to be the case with brilliant ideas, this one outgrew the del Olmo’s apartment and into the sisters’ childhood home in Mallorca—a magnificent, sprawling house in the small inland village of Pórtol. “It felt like the perfect playground to test our concept and bring it into the world,” del Olmo says. Since the beginning, her aspiration has been to create a sense of community and conviviality; a space where artists could go that felt like ‘home’—not just in the physical sense, but “the feeling of being taken care of and supported; feeling part of a bigger network of people, knowing you're not going through life alone.”

The Balandra way of life is still suffused with the Sombremesa mentality. “Food is at the core of everything we do, including the artist residencies. We have the most amazing meals, night after night, with everyone sharing and cooking things from their own backgrounds and cultures,” she says. “Now more than ever, a table represents a holding ground for all our needs that are not being met in our daily lives, like physical connection and interaction; a sharing of cultures in an open-minded, safe space; slowing down and being present.”

The residencies are a chance for experiential play in the kitchen at a relaxed pace, akin to an artist or writer’s retreat. “They allow for flexibility and fun,” she says. “Travelling and learning about different ingredients and cuisines is really beneficial and exciting, especially for young guests who can put exploration back into their practice. At the end of the day, food is an art form that we interact with daily, it makes sense to give it a space for expansion and exploration, like residencies do for artists.”

One such guest chef was Laszlo Badet , the Swiss-born, Paris-based culinary artist and model known for her elegant creations—think swan meringues and life-sized raspberry pies. Following successful residencies at Château de la Haute Borde and Dame Jane, and accompanied by her partner, the Parisian photographer and “excellent cook”, Léonard Méchineau, Badet arrived at the doorstep of Casa Balandra in the summer of 2022.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

During the week, Badet encountered the “most beautiful fish and seafood [she’d] ever seen” at the local markets and worked with Mallorcan produce to cater two wine-pairing dinners, each featuring flavorful fare inspired by her surroundings. Menu highlights included grilled sea bass enveloped in fig leaves with wild fennel and zucchini ribbons stuffed with fresh goat’s cheese and orange.

The couple’s week-long residency was characterised by generous hospitality and a sense that they were part of the family, perfectly mirroring del Olmo’s vision for the guest house. Badet fondly recalls the splendid setting in Mallorca and the relaxing yet exceptional atmosphere of the house and those staying there.

With a curious palate and warm energy, Badet is on a trajectory that will one day see her opening her own restaurant, café, or guesthouse. For now, she’s happy exactly where she is: creating community through residencies and with the Parisian vendors— among them florists, winemakers, and butchers—who help bring her events to life.

Perhaps nowhere is the communal spirit of residencies better on display than at Casa Lawa — a colourful and community-oriented guesthouse in Sicily founded by Polish-born, multi-hyphenate creative, Lukas Lewandowski , and his husband, Merijn Gillis.

View this post on Instagram

Talking to Lewandowski is a lighthearted reprieve from a world that can often take itself too seriously. Morning meetings with his Australian head chef, Lisa Jane , are punctured by floods of giggles, and a nearby beach functions as one of Casa Lawa’s alfresco dining areas, where he’s hosted dream-like dinners with everyone from photographer Lucy Laucht to cook Kirthanaa Naidu. Here, guests can sign up for baking, pasta and harvesting retreats, eat sumptuous spreads put on by visiting chefs, or accompany Lewandowski on visits to his local bakery, opened in 1880.

View this post on Instagram

The Casa Lawa ethos is simple: life is made to be enjoyed, food is a conduit for connection, the kitchen is a place for chefs and guests to let loose and have fun.

“Cooking together releases the funniest parts of ourselves to each other — it’s intimate and enables you to get to know others on a deeper level” he says, before describing a scene that could have been plucked straight from my daydreams. “Every day at Casa Lawa becomes a kind of exhibition, a performance in the kitchen—seeing people whipping up butter, frying sizzling eggs, covering tables, making beautiful fruit plates, with music in the background or the sound of birds chirping in the morning.”

It’s hard to believe the design-led guesthouse—which inhabits a former 200-year-old converted palmento (a grape press typical of the region) and is surrounded by 10-acres of fruit orchards—has only been open to the public for a year. Alongside the local community of winemakers, restaurateurs, bakers, and farmers in the area, Lewandowski is bringing a steady flow of creatives from around the world to the foothills of Mount Etna.

View this post on Instagram

“I never would have met so many beautiful souls who are passionate about what they do if I only worked with one chef,” Lewandowski says. “For me, residencies are really about giving chefs the full freedom to express their style and personality through Sicillian ingredients and seeing what magic comes out of this… I love to work with people temporarily, where we all get the best out of it, learn from each other, and at the end of the project, we’re still friends.”

View this post on Instagram

After wrapping up the season last year, Lukas visited a string of cities—Milan, Rome, Napoli, Warsaw, Athens and London. With a few exceptions, he was underwhelmed by what he found. “There are too many places creating the same concept, with small plates and natural wines,” he laments. “Restaurants are missing personality—it all looks and tastes very similar… I fear that some of these new concept restaurants are more about earning money rather than hosting people. Working in the restaurant industry for sensitive people is also nearly impossible without putting out their flame. I believe chef residencies are a revolt against these things.”

View this post on Instagram