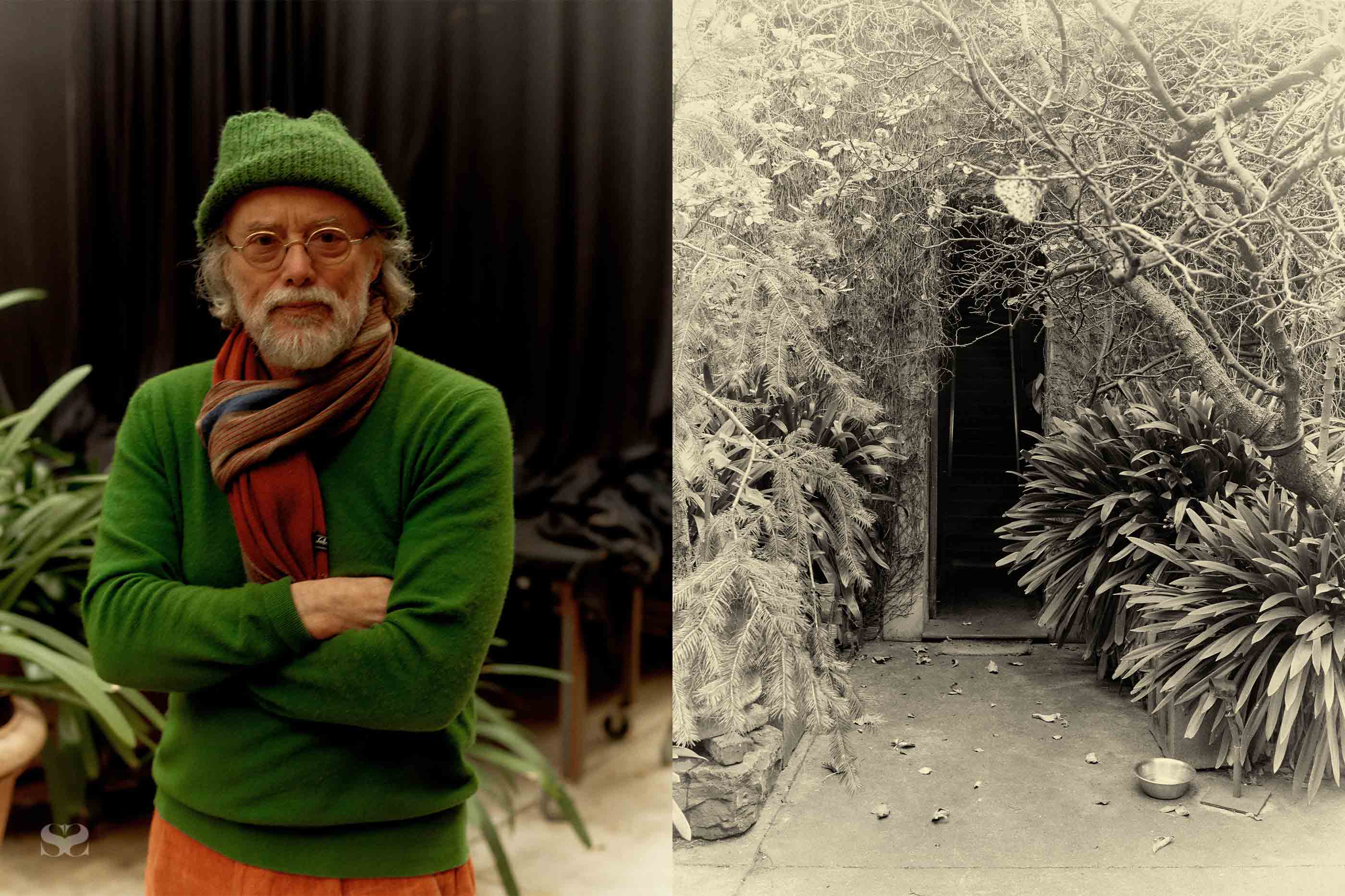

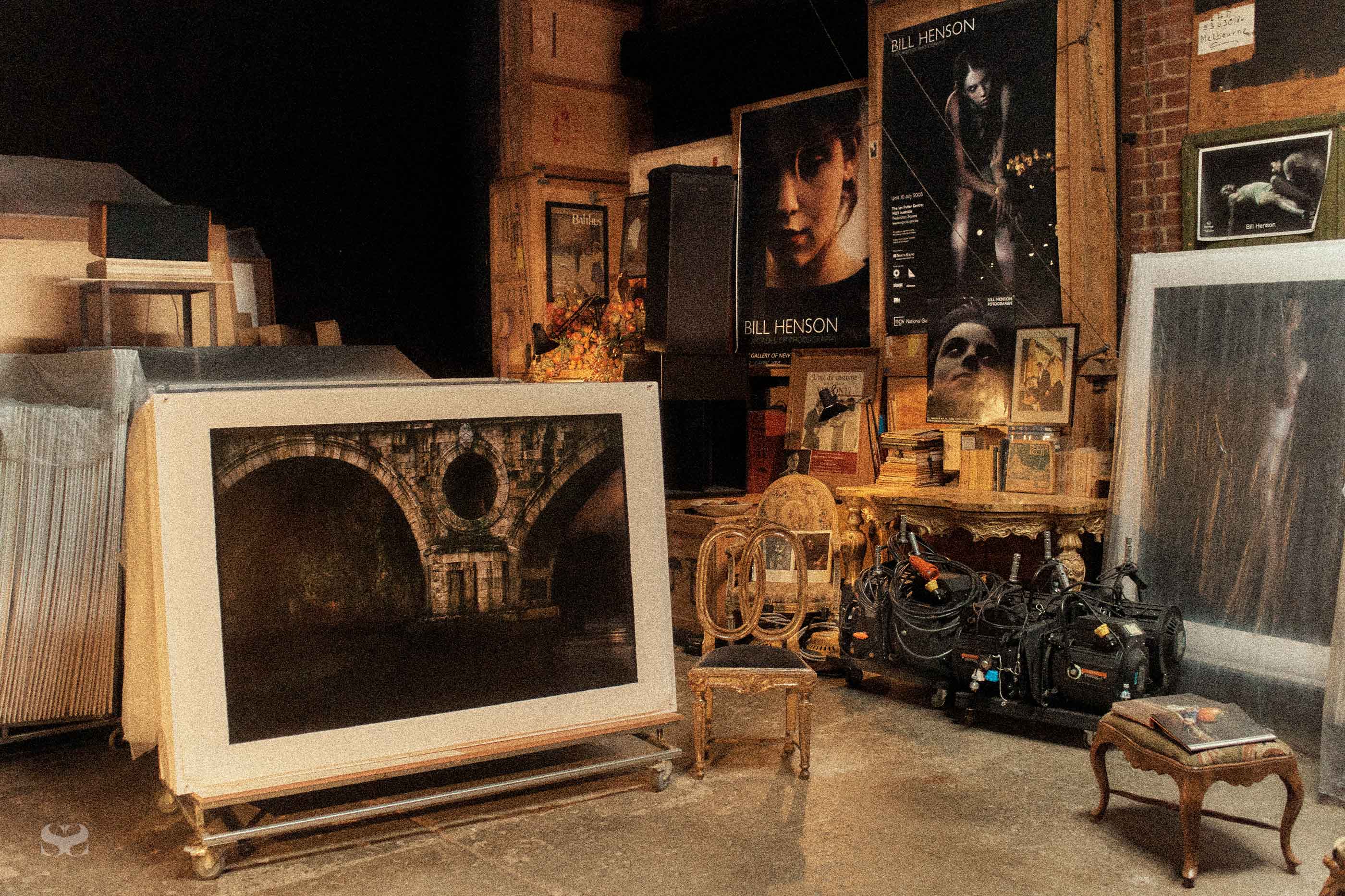

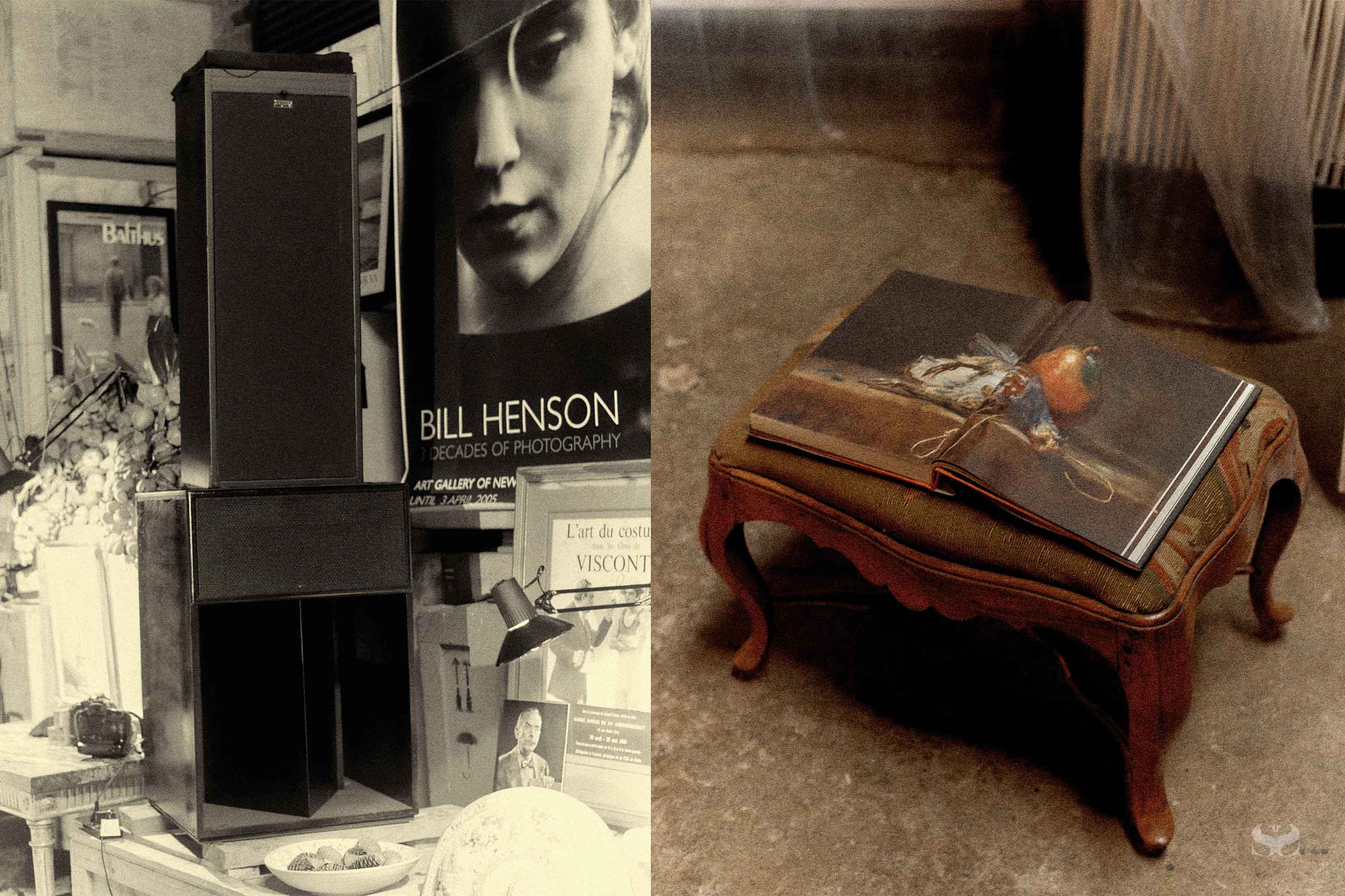

When the master of darkness, enigmatic Australian photographer Bill Henson, meets with his tailor, Tom Riley, the cloth they discover is a stimulant for conversation around the physical things in the world – especially how one’s imagination navigates just those things. From his home in the inner Melbourne suburb of Northcote, Henson recognises the spirit of place, his deep connection with his garden and the impossibility of Opera.

“At least it recommends the truth, which is what all great art does.”

Bill, when you come and see me, we are lucky enough to indulge in all sorts of lovely things; film, colour… but, what really strikes me is when we talk about gardens. Have they always meant a lot to you?

My sister and I grew up gardening with my mother, who was a very keen gardener, from our earliest years. It was just what we did, and we all love doing it. The whole question of whether a mossy rock should be moved three degrees to the left, so that it catches the late afternoon sun, and how that was going to affect the roots that have been there for 50 years, these are the kinds of conversations that trickle along. So certainly, it was the way I grew up and with who I grew up. I think ultimately it’s not so much about being a plantsman, but more what pleased the eye and that’s where all of these things you mentioned at the start mesh blend into a sensibility that’s drawn to one’s own personal sense of beauty.

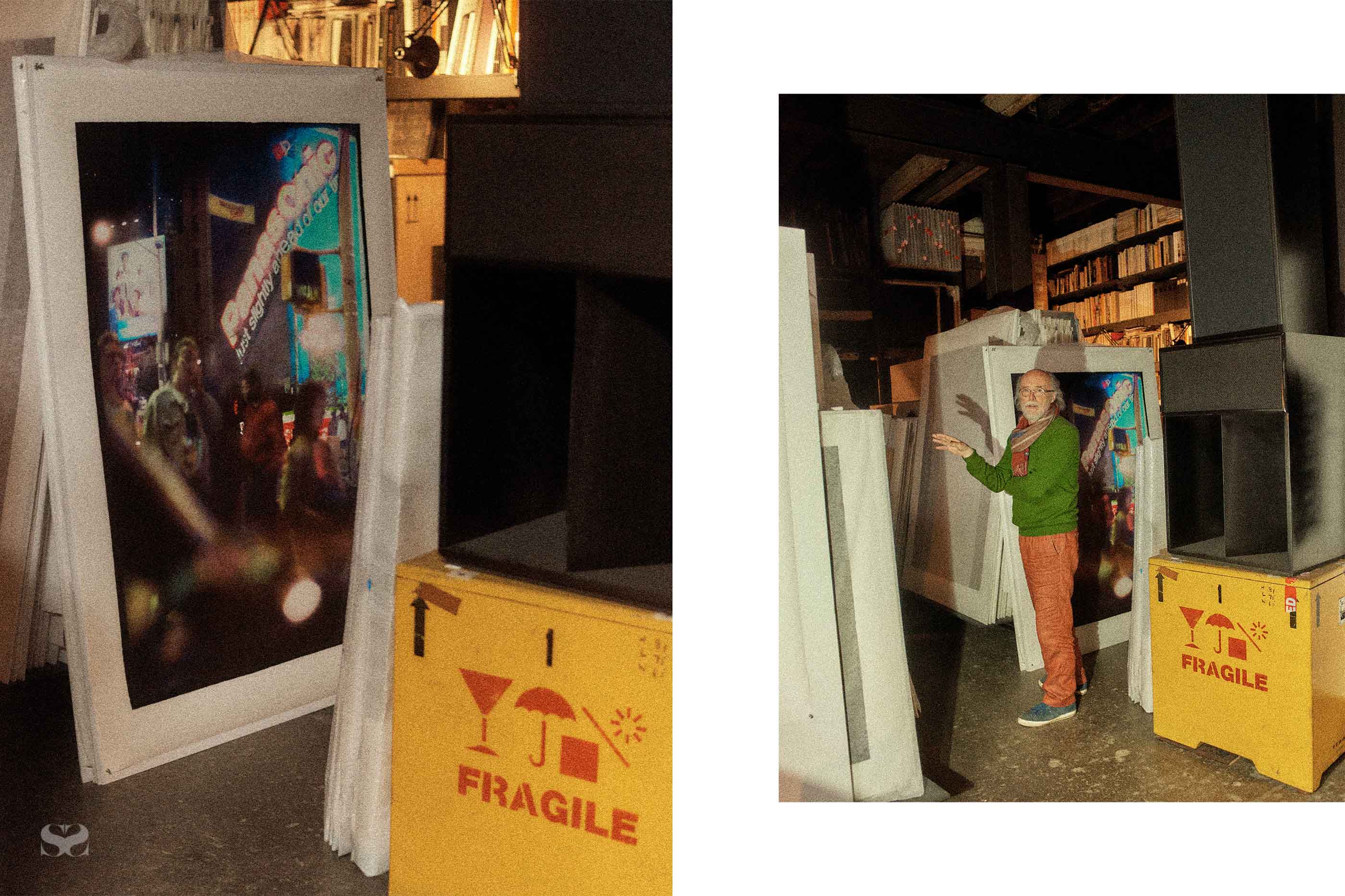

Sometimes when you pull out a swatch of beautiful old herringbone fabric that some ratbags are making in Scotland, it looks like it’s 200 years old, but it has beauty and of course, time lends things a patina, and sort of adds to those depths of beauty. I think, in many respects, it’s rather like looking at a fragment of classical sculpture – would it be as moving and as interesting for us if it was brand new when it was first created with coloured paint all over and basically looking like a plaster cast? I doubt it; it’s the marks of time. To produce something now that suggests those things through texture and colour is always really interesting and rewarding. That can be in paint, it can be in photography, it can be in anything. It’s not about the kind of design, it’s not about any particular aspect of the object, it’s just that sense of the question of, you know, things in the world – physical things – and how your imagination navigates those.

It’s really the suggestive potential of a beautiful piece of fabric, whether it’s a silk, whatever it might be. These things, they all inhabit the physical world, but they are also so much more, that’s abstract. That’s where all this stuff is the same and gardens fit right into the middle of that because gardening is probably the closest culture comes – man-made culture – to nature. It’s right on that border and it’s a bit like talking about the senses. Probably smell is most difficult to have to mediate for anyone else, and it’s the thing that has that intimate and immediate association which is entirely your association of a particular smell or particular point in your past, in a particular environment. It’s very hard to separate from the memory so, if any kind of gardening is the closest culture comes to nature, I think [it’s] really in that respect. It’s a great, what can I say, stimulating instrument, because of the fact that it’s constantly changing that it’s affected by plants, insects, animals, the weather, time of day, the seasons, the time of year, all of these things completely change the look of a garden when you’re standing in it. Yet, a garden by definition is a manmade thing. It’s not wilderness nature. It is by definition, manmade, but it suggests so much to you that you can then bring into other areas, whether it’s making a photograph, or whatever it is.

Is there a garden that’s impacted on you more than any other?

It’s probably the garden I grew up in, which is our mother’s house. We worked in that for, on and off, 60 years. I tried to salvage as much of it as I could once the place was sold, sometime after she passed away. You can take plants and you can take rocks and objects, and even big trees and all that sort of thing, but I don’t think the spirit of place survives, which is everything about your connection to the actual shape of the land and the aspect of Northern temporal evolution of it.

If you were to build your archetype of gardens, in your imagination, where would it be in?

Right here? I mean, you can always do a Norman Douglas and decide that you’re going to be responsible for the reforestation of Capri, which he was. When he first saw it, in the late 19th century, it hardly had a tree on it. When he left the British Foreign Office, he was in Russia, I think, during the Bolshevik Revolution, but when he left, he was classically trained, loved the Mediterranean [and] he was thoroughly kind of immersed in the history of Mediterranean culture. He ended up on Capri where he died in 1952 and all these people would come to him and pay homage.

Robert Helpmann went in fact, the Australian connection. But it was restoring the stone pines and all the trees that are on there now and when he died, the mayor of Anacapri I think read a speech and it was about something dear to Norman Douglas’s heart: The speech was about reforestation. It wasn’t about his literary reputation, which was significant, it was about his love of Capri. Chatto published a volume in the 1930s. In there, I think he says he loved coming across in a boat and seeing these Italian Cypresses, which he planted. As they took hold and started to grow and seeing them coming across the Bay of Naples and turning into large trees, I love that. On Ischia, the same thing was happening because William Walton, and his wife probably more than him, created this fantastic ‘La Mortella’. They had to bring water in a tanker. Yeah, because there were no pipes across the islands when they started that. They built it in a stone quarry that was completely barren.

One other thing we get to indulge in is film, cinema. Obviously, is it an important thing to you and do you have a handful of films that you think are important, or important to you for some particular reason?

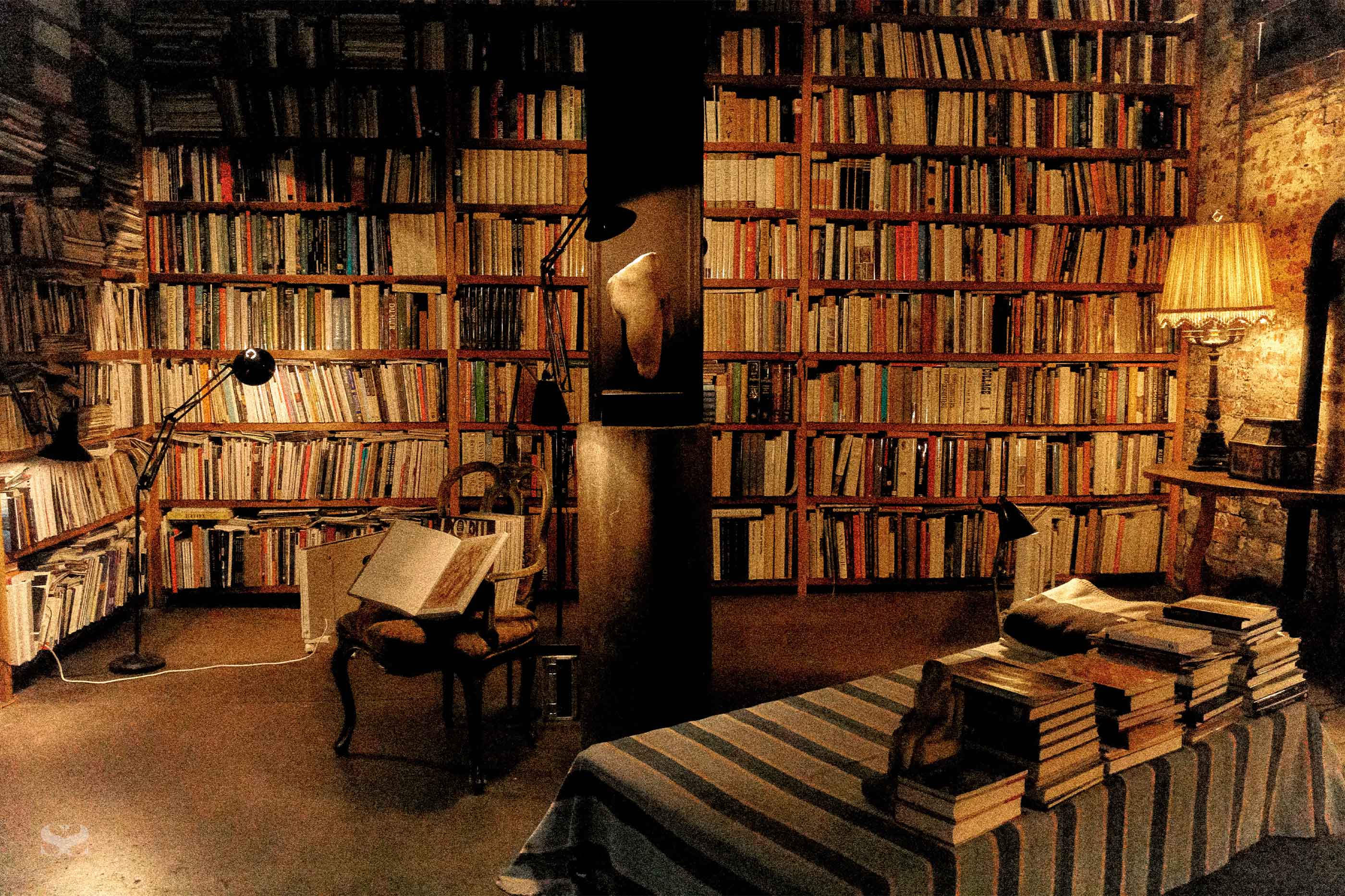

There are certain films… I think most people have these sorts of things you can just watch again and again, and it’s endlessly interesting. Going back and visiting one of my favourite paintings, which Titian’s Nymph and Shepherd in the Vienna gallery, I could just spend a week in Vienna sitting on one of those grey velvet couches, looking at that picture all day, every day of the week. It just keeps on going. There are a sprinkling of films that have had that effect on me.

Long Live The Lady is one of my favourite films. It’s so it’s so funny, but it’s also so beautiful, and of all the characters and the madness. One of the things I love about that film and those ratbags coming together, magnificent ratbags, is how beautiful [Emmanuelle] Olmi was [able to bring] all of these strange people [together], gradually reveal themselves through their behaviour, the odd glance and all of their little proclivities unfold in the film as it goes along.

There’s some great characters. I love the character of the grumpy, bearded man that flies in his biplane and lands in the dark in a paddock and then comes in and – obviously the favourite – moves his place card from next to her at the far end of the table; everyone else is gonna move on one place – “I’m not going to sit next to you.” There’s so much going on. It’s got that forgiving, kind of, you know, the sorts of things that the Italians are so good at accommodating, which makes their culture so rich.

I have certain directors who I have always really liked it. They tend to be, in a way, very conservative. I remember when they screened Visconti’s The Damned, [Federico] Fellini and a whole bunch were in for the premiere and Fellini jumped up and he goes, “The master! Genius!” Then, somewhere else, he’s being interviewed in the press after the premiere and he says, “He’s the purest, the most conservative of all of us.” In that sense of conservatism, I mean, taking a long view…

There’s a great biography of Visconti by Monica Sterling, called A Screen of Time. So, the things that reinforce it, as with most art, is the more you learn about something, the more it becomes more mysterious, the more you realise how little you know about it. That happens with a lot of Visconti’s work for me. I like his later work even better than the very early ones, even though they’re great.

But they’re destined to live, aren’t they? They’re going to keep living and living and living.

They feel increasingly like a documentary, like a deliberate documentary, even though there’s a screenplay and they’re actors and all that sort of thing. It’s been written by a few of his friends and the screenplay has been written by people. You feel it and he does things to make subtle differences to the way it feels. For example, in The Leopard with Burt Lancaster, he had all the accoutrements that The Prince of Salina would have in his portmanteau, shut. Yeah. It was never opened in the film but what was in there was what he would have had.

The stuff was in there and everything had to be real. Visconti, he used his connections to get all of the state jewellery that was in various museums, and treasury in Bavaria. So, when you see Helmut Berger, or you see these characters, they’re all wearing real stuff; he has a real crown put on his head.

The idea behind it partly is that, if you want to make Lancaster to feel like this person, then you give him all the actual stuff. It’s – I’m going to draw a slightly long bow – but I’m saying that’s a little bit like using shooting film, as a photographer or cinematographer, as opposed to shooting digital. The reason being that if you’re making a film, you’re always using someone else’s money, investors money, producers money.

So, you have a client, where you have someone that you’re responsible to have a budget and you’re responsible for. If you’re shooting on film, at the budget with all of these films, you had enough film to do three takes, then that’s it. The order of concentration is massively greater and I said this to an actress that I know who works in works in the States, and she said, “Oh, yes, you’re still shooting film?” and I said, “Yeah,” and then we talked about this and she said, “Oh tell me about it.” She said, “I’m on set in hair makeup, [and I] just wander through [and] people just do things, because [the film is] just a harddrive spinning in the background. It does not cost anything.”

It makes a huge difference to how people behave, and Visconti really understood all of that. He understood how you very subtly introduce this sort of sheer weight of history and somehow it’s embedded in the film. It’s embedded because it’s affected the way the actor’s behaviour becomes more real. It’s a bit like Opera – if you look at it dispassionately, it’s outlandish and ridiculous. The plots are always absurd and incongruous and the relationships are impossible and outrageous. But, it’s when all these things combined with the power of the music that it doesn’t matter – it becomes real. At least it recommends the truth, which is what all great art does. That is the truth.

The English Romantic poets used say that a lot but of course, the person who put it best was Plato. You know, “beauty is the splendour of truth.” You can’t get better than that.

“Art destined to live shows an aspect of a truth of nature, not a coldly worked out exercise.”

Exactly. And, which of the Romans said, “a man who has a library in the garden or a garden in the library shall want for nothing”? I think that might have been Cicero. That’s kind of pretty close to the mark.

To experience RUSSH Home in its entirety, issue one will be available on newsstands from October 20 and through our shop. Find a stockist near you.