I have read the text messages of people I love repeatedly. In their physical absence, the evidence in my phone sustained me. When my relatively distrait father passed last year I took to looking through his messages to try and stick things together before any other account. Here was a message from a Caroline: Meet you there?, one from his bank indicating his name was Andre not Adrian. I went over the credit scores, loan assessments, health care access, refinancing requests, welfare administration, defence benefits. The remaining and alive data map.

There can be a thrilling apricity in knowing someone is thumbing through your texts on high rotation, a kind of communion to your memory. Screenshotting into offline folders to take on planes just in case you couldn’t scroll back to retrieve. Early messages held as proof and a beginning scaffold for a future. I’ve been privy to co-writing the script of texts to others’ lovers, dealt with break ups, made connections in other countries through various apps, made myself cum, disclosed nudity and sunk into the inbox of partners’ phones to read between lines and stake out a truth.

In a lot of ways I had taken that ‘privacy’ existed as a realm between the giver and receiver of transmission and that there was a remnant in any communication depending on the server.

I had nothing to really ‘hide’. Apps are used all the time to promote a kind of limitlessness and consensual voyeurism.

However what we tend to think of as a vast pool of technology in reality is generated by a small and homogeneous group of people. (A guess as to what their age, sex, and racial identity are.) Deciding to make text messages and the phone the stage for my next performance felt fitting amidst a desperate time.

There is a phone line in Japan called the Kaze no Denwa, aka the wind phone. In Otsuchi, in a garden setting, sits a disconnected rotary phone positioned inside a glass booth that allows callers to send verbal messages to those they’ve lost, which the wind then carries away.

Otsuchi resident Itaru Sasaki is behind the phone booth. Sasaki lost his cousin in 2010, one year before the tsunami devastated the small town. At first, only Sasaki used the phone, in an effort to stay connected with his family whilst mourning.

“Because my thoughts couldn’t be relayed over a regular phone line,” said Sasaki, “I wanted them to be carried on the wind.” I’ve come to think of this one way of communing as an honest and clarifying purge. That speech and language spoken are beyond conscious control particularly in grief; they come from another place, outside consciousness, within discourse to loss but also in unconsciously talking to another alive or dead.

I’ve made a career with ambivalent and at times enigmatic methods of communication. Working predominantly as an artist within the realm of dance and choreography.

When this pandemic settled in, I was in a ripe position to be somewhat alone yet still thinking about how to transmit.

Like every other overworked and underpaid labourer schlepping along I was ready to take at least a week to ~ slow down ~ I deserved this ‘break’.

The world was also stopping, I didn’t have kids, my house was nice enough. I was going to re-organise my website, sing more, prioritise handstand practice. Of course none of it happened. I almost sped up by being lumped with the task of going digital for work and; I was fucked off about it. We were meant to flatten the curve not our already impaired apparatus of being.

I was loathe to do online dance classes, I hated the continual mini monologues happening in every talk – I like being interrupted and also being able to disagree in real time. Dancing on Zoom with a one second lag sucked the thrill out of it; not being able to witness, IRL surveil and perv on others and have them do the same to me. I wanted to be an object within the room of others again – I was put up with a watery black mirror and my phone / laptop was my only and more often than not disappointing interface.

Being commissioned by the Art Gallery of New South Wales for Hyper-linked: an exhibition for the digital realm brought a tinge of relief.

I was an artist that was apparently: alert to the almost paradoxical fact that we are experiencing mass disconnect in an age of hyper-connectivity.

Examining the role the internet plays in shaping our lives and the ways in which we communicate, bearing witness and paying tribute to our networked selves. Originally I had been asked to do something for the Kids program; after my rather dismal attempts of maintaining my own indolent attention span with online education I declined this first offer.

In her text for Hyper-linked curator Isobel Parker Philip noted that: “In the space of a few hours, I alternate between calls with my colleagues, my therapist, my mother, my boss, my partner, and my friends without once moving seats. Sometimes I’m not even wearing proper pants. My language, gestures and intonation change with each encounter. It’s like I’m opening and closing different tabs of my life in rapid succession.This feels fungal. It’s a form of world-building. I spread myself across otherwise insurmountable physical distances by interacting with others. This is a collaborative ecology.”

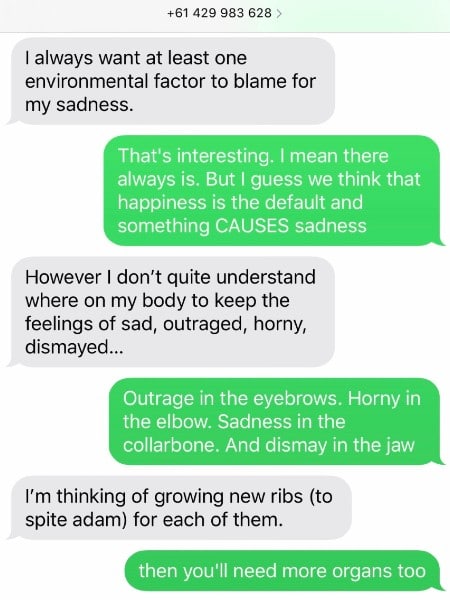

Cass is text bot named after the priestess Cassandra of Apollo who in Greek mythology was cursed to utter true prophecies, but never to be believed. In modern usage her name is employed as a rhetorical device to indicate someone whose accurate prophecies are not trusted. Text bots are traditionally used to serve a function to communicate a future sale. And while Cass is not always prophetic in her texts (nor will she sell you anything) it was my aim to make something that could forecast a future where tech is employed to disrupt its more ‘professional’ tendencies.

Being clear and clearly rhetorical in diction was difficult when trying to forge a flow chart with programmers meant learning how to do very basic coding, a skill I never thought I would ever have. (I now think of myself akin to Jolie in Hackers). It was bewildering to listen to male developers circumlocute and describe Cass. Before the name was decided and while talking through the project I was met with the assignment of a gender and even an age: “She’s like a bratty teenager”, or another characterisation of the bot being a “sentient” being.

In an appraisal by Parker Philip: “Cass isn’t hardwired to help us. She’s neither a maternal figure nor a PA. She’s got her own agenda and has taken control of the conversation. She spins stories and asks rhetorical questions. She cares about your response only insofar as it allows her to keep going. To be heard. Because that’s the very thing her namesake was denied. In Greek mythology, Cassandra was a priestess cursed to forever utter prophecies but never be believed.”

“This Cass is a millennial herald. She’s not easily distracted, she’s multitasking. And she has many things to say – you can choose whether or not to listen.”

Cass doesn’t feel like a brave endeavour – if I’m honest I have pettily planted texts that I hope are read by enemies and exes but there is something even in that admission. To use the medium of my own petty ‘symptom’ and alchemise it to make work – to seek out the language of atonement. Tech has become the container that seems to hold a brimming desire. Shoshana Zuboff writes, “Ubiquitous connection means that the audience is never far, and this fact brings all the pressures of the hive into the world and the body.” The audience and performer in this case can be summoned at any time.

Text +61 429 983 628 to begin your conversation with Cass. (T&Cs apply).

This article first appeared in the 'Courage' issue. See more, here. See what else Amrita Hepi's been doing in isolation here.