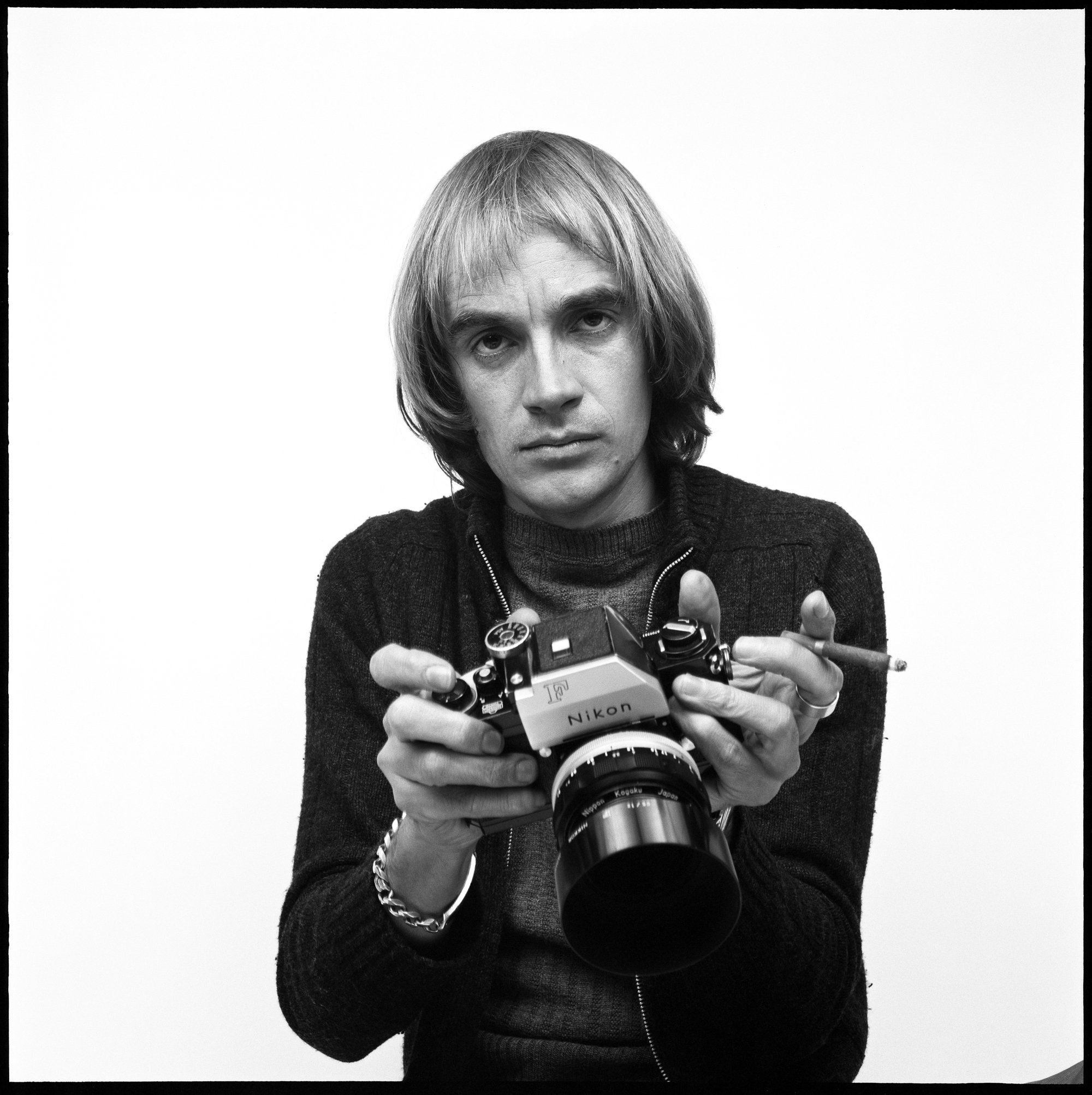

British-born artist Steve Hiett specialised in summoning the feelings in between. His photography and music radiate a warmth of elegant, subtle poignance, with sharp aesthetics serving only to deliver the message, lost in and always on time. Starting out in swinging London playing in short-lived band The Pyramid, Hiett drifted into fashion photography, eventually relocating to Paris where he would stay and make his most potent works in both visual and musical form.

One of those works is Hiett’s 1983 album Down On The Road By The Beach. Some co(s)mic lost in translation saw Hiett in the studio in Japan conjuring the sound of sunbaked, blue-soaked coastal afternoons via waves of deft blues guitar at soft and gently narcotic tempos. Initially released in Japan only, in 2019 the record is having a second summer in the sun with a wider release and reappraisal. Another of those works would be Girls In The Grass, music recorded on laconic Saturday afternoons in a friend’s Parisian atelier in the 80s, until recently lying dormant and unheard.

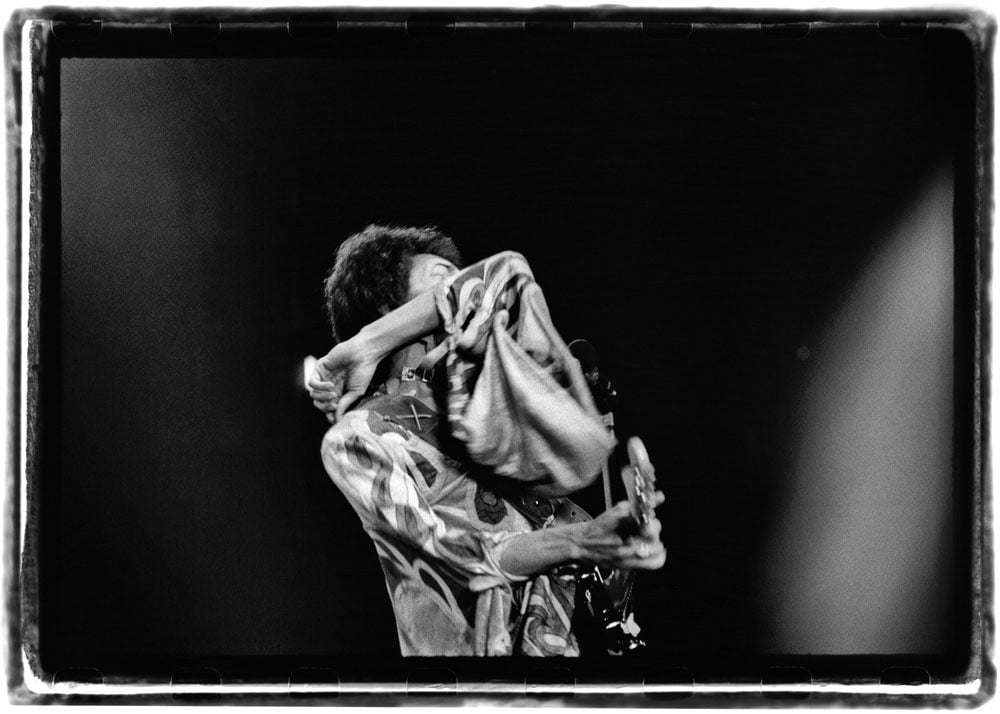

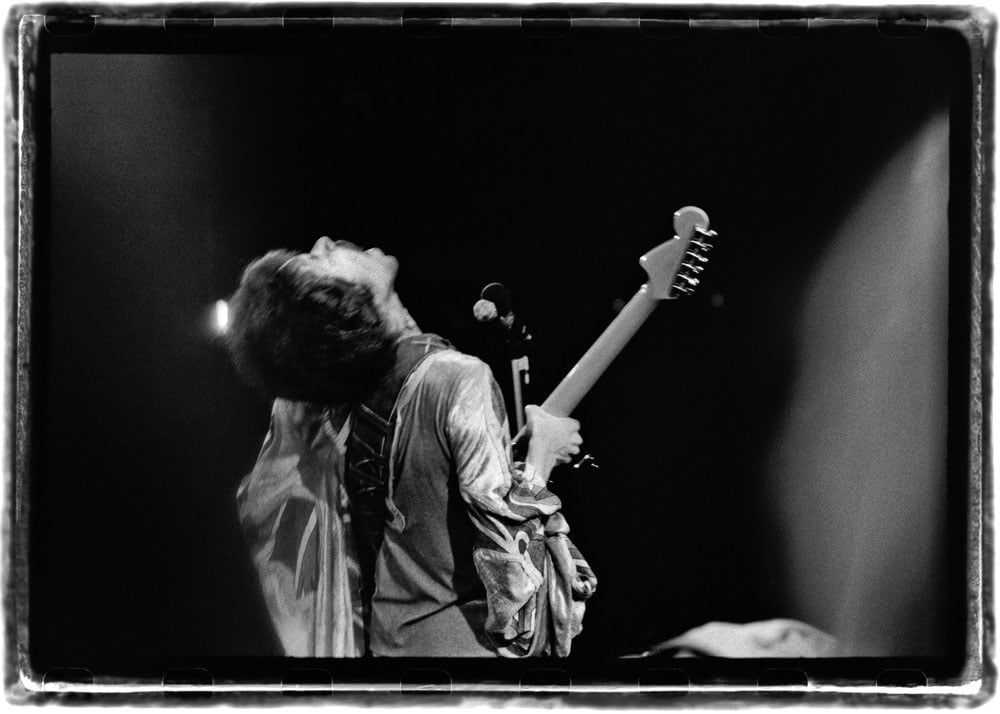

Hiett’s photography swam in deep colour and alluring light, eschewing typical framing and experimenting with daytime flash. An off-beat pop aesthetic permeated his work in music, art and fashion photography, but all were delivered with a flair inimitably his own. Having shot the Beach Boys during a tour stop in Birmingham, in 1970 Hiett had a chance to attend the Isle of Wight Festival on behalf of Rolling Stone, capturing Jimi Hendrix in full flight at the height of his powers. The Rolling Stones, Miles Davis, The Doors and Joni Mitchell all crossed Hiett’s lens; however the bulk of his photographic work was in the fashion world, shooting for The Face, Kenzo, agnès b., and extensively for French, British and Italian Vogue, among many others. Spontaneous, experimental and adaptable, Hiett’s fashion photography exuded an irreverent, fresh artistic bent that placed him among contemporaries like Peter Lindbergh and Sarah Moon.

“His photography was an inspiration to me too,” says Simon Kentish, an English art director who collaborated with Hiett on Girls In The Grass. “I don’t know if you’ve noticed his colour pictures in nature; by looking at impressionist paintings he’s understood that the shadows are never black – they’re purple, blue, green – he gave colours to shadows when he photographed nature.”

“Steve once explained to me his theory of taking a great picture ... he said, ‘I’ve decided to do everything they told me not to do’.”

Over time the work was compiled in art books and seen in exhibitions internationally. It was one of these exhibitions that led Hiett to Japan, where Down On The Road By The Beach was conceived. Invited to Tokyo under the impression that he was to check proofs for the exhibition from which the album eventually took its title, Hiett was miffed but not in opposition when he was whisked from the airport to a studio to record an album with a band of hired guns. Overwhelmed by the Japanese crew’s exceptional professionalism, Hiett told them to go home and instead flew in a friend from New York, Elliott Randall.

“We had a mutual friend who owned Blue Rock Studios in NY,” Randall explains of their meeting. “I was invited to record there with Steve. We hit it off really well, and continued our search for the lost chord together.” A well-known session gun at the time recognised widely for his work with Steely Dan, Randall responded to the Tokyo dispatch enthusiastically. “I thought, ‘Oh this could be really fun’ ... and proceeded to get a Japanese work visa. We had a fantastic time in the studio! Steve’s knowledge and understanding of music (and the arts in general) was all-encompassing, and this shone though in the making of the record.” If there was unexpected stress from the demands of making a record on the spot, it didn’t come through in the sessions (or indeed the record). “We had quite a few moments of giddy laughter,” Randall says. “Hardly anything was sketched out. A lot of what we did was making it up on the spot, and I have always loved the ‘seat-of-the-pants’ approach to innovation.”

Intended as a musical accompaniment to the exhibition, the record has in the time since circulated among aficionados as a kind of Holy Grail guitar work, and with good reason. The music Hiett recorded in Tokyo drips from the speakers, seemingly simple, minimal arrangements of reverbed guitar and bass that plunge into the deep blue, occasionally mixed with drums, keyboards and vocals that sound as if they’re lazily melting into the sand. For Simon Kentish, it’s a record forever linked to the summer. “It’s a beautiful album, it’s my favourite when I’m in Italy and it’s a hot day and I’m in the house cooking.”

“He’s breaking all the rules like a jazz musician, in the way he takes his pictures ... in the way he does his music.”

Like Hiett, Kentish moved to Paris in the 80s and cruised in similar social circles, the two becoming fast friends in the French capital. “Within the first few weeks of arriving in Paris we met and I was looking after his cat. We started talking about graphics, and then I saw he had a guitar hanging around so we jammed together and things kind of took off from there.” The two of them got together every Saturday for loosely structured jamming in Kentish’s basic home studio until Kentish’s girlfriend came home from work, and Girls In The Grass is a collection of recordings from these afternoons. On them Hiett sends swells of shimmering guitar in Kentish’s direction, which Kentish captures with his DAT recorder and situates amid subtle synth pads and soft drum machine rhythms. Given they were never intended for release, the songs veer slightly more sketchy, though the sound feels more of the moment than Down On The Road By The Beach’s heat hazy timelessness.

“There was no underlying narrative of ‘we’re going to turn this into great music’,” Kentish says. “We just jammed for the fun of it. We started off jamming really badly with a rather bad drummer, sweet guy, rock ‘n’ roll because Steve did love a bit of your old Chuck Berry. Then we started doing graphics together because he trusted my guitar playing so he trusted my graphics, so we worked together on a few projects. I moved into this lovely artists’ studio in the 14th [arrondissement], beautiful space with a beautiful fender guitar amp and he’d just come around to plug his guitar in. We started jamming there and I had my bass guitar and I thought, ‘fuck it this is sounding too good we should just do it’, so I bought sequencing hardware and a DAT recorder and we took it from there.”

Kentish believes Hiett’s approach to his art can be summed up in a word: jazz. “He had the feeling for jazz, and I think Paris is a jazz city. Steve once explained to me his theory of taking a great picture; he showed me a little booklet that comes with your standard camera and it said, ‘Avoid shooting with the sun directly onto your subject, avoid a telegraph pole that looks like it’s growing out of her head, avoid avoid…’ and he said, ‘I’ve decided to do everything they told me not to do’. And if you look at his pictures, he has got pictures of girls with their eyes all screwed up, even crying from the sunshine, but look at the colour of that sky behind them! It’s such a blue that you can’t believe, which you wouldn’t get if you did it how they tell you to. He’s breaking all the rules like a jazz musician, in the way he takes his pictures, in the way he does his graphics, and in the way he does his music.”

“He was a bit like Jane Birkin ... he had a well-practised ‘I don’t speak French’ kind of English way of speaking French.”

Randall remembers Hiett as “a lovely human being – great sense of humour, compassionate and insightful; a true friend. I miss him a lot.” Kentish, too, is effusive in his praise for his friend. “Everyone would say he was kind of modest and withdrawn, but he quickly warmed up. He had a very humorous view on life, and he was observing all the time. He was a bit like Jane Birkin … he had a well-practised ‘I don’t speak French’ kind of English way of speaking French – he could speak French perfectly. And he had lots of humour.”

Sadly, the sun set on Steve Hiett this year, mere weeks before his two albums were given a new life. According to Kentish, in spite of his illness Hiett continued to create throughout. “He was taking pictures and playing his guitar right until the end. I know he’d be sitting up in his enormous apartment looking over the Buttes Chaumont with his 137 guitars to choose from and putting in the hours,” Kentish says. Fortunately, the work Hiett left behind leaves a deep impression.