Paco Rabanne, who died on February 3, 2022, was the high priest of industrial couture. He was 88, and lived a life that was daring, provocative, and authentic in so many ways.

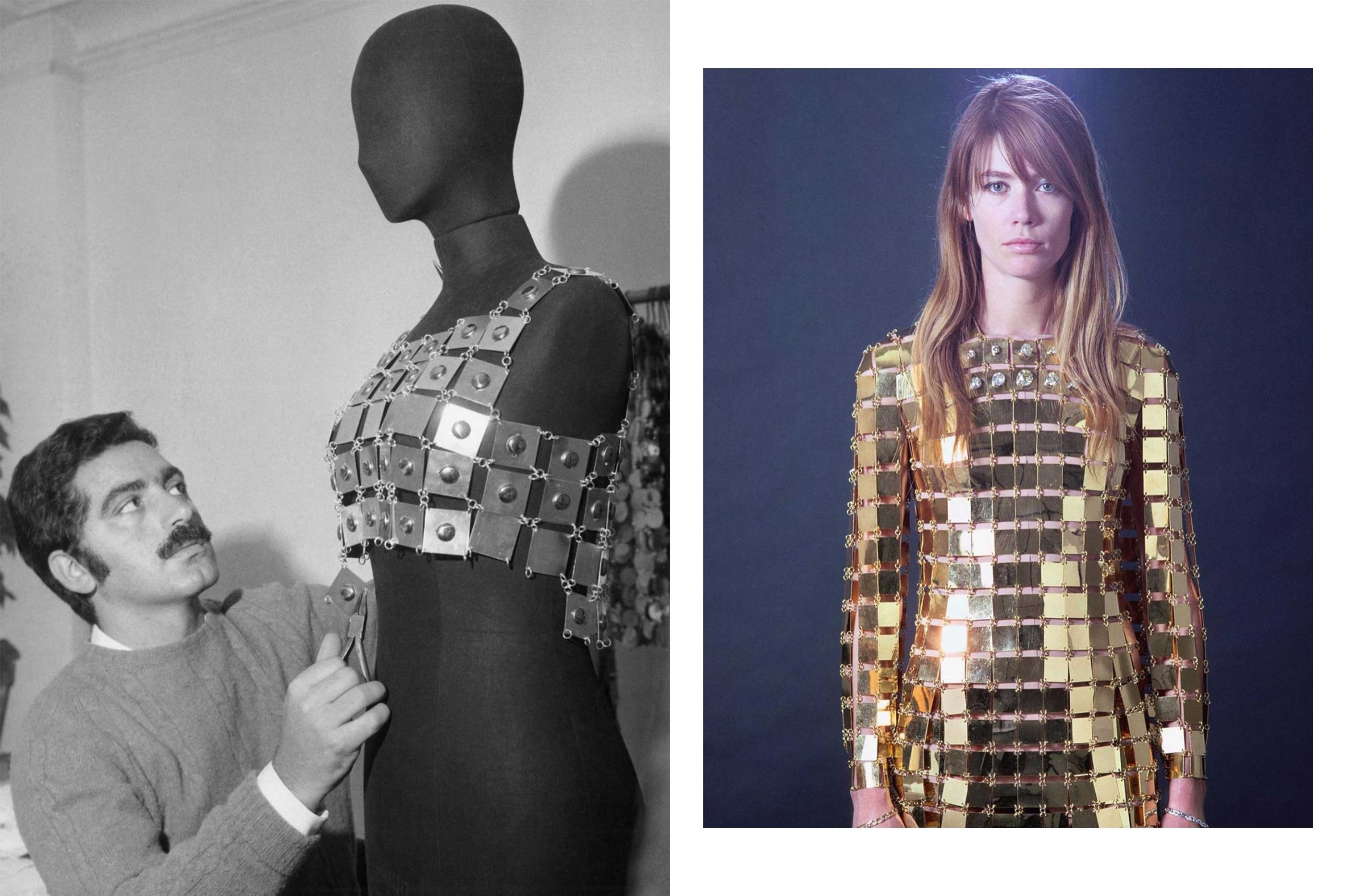

It was for his first collection in 1966 that this was evident. He titled the show: Manifesto: 12 Unwearable Dresses in Contemporary Materials, and it was exactly that. Out on the runway, barefoot models showed a collection of mini dresses made of pieces of metal or Rhodoid, linked by wire ties so that they moved with each step, forming futuristic shift dresses that would set the tone for the rest of his career, even if they weren't wholeheartedly received by the dominant fashion community at the time.

View this post on Instagram

While Vogue's Diana Vreeland was on board, and Peggy Guggenheim was purchasing pieces for her art collection, Gabrielle Chanel was making a point to draw a line in the sand in Paris. New York may have him, but the city of love wasn't quite sold. "He’s a metalworker not a couturier.” she once famously proclaimed.

It didn't matter. As a student of architecture, Rabanne was quite confident with his work, already producing metal jewellery and buttons for the likes of Balenciaga, Dior, and Schiaparelli at the time. When his 1966 collection was released, he didn't need to approval of anyone, the Spanish designer was already planning how to bring a sense of democracy to couture with marketing strategies like disposable, vending machine dresses for frequent flyers and DIY kits of rings, discs, and pliers so that women could make their own dresses at home, especially after witnessing the coverage that Rabanne was already receiving.

View this post on Instagram

“The first time I went to one of his shows, I remember saying: ‘What is going on here? I don't believe it! It’s so beautiful and so different! Gladiator dresses, a suit of armor, a warrior, the new male!” Polly Mellen told The Times in 2002. For Rabanne, warriors like Joan of Arc underpinned his creative expression, offering a kind of sexualised armour that had not been done in fashion before, making him the obvious choice to costume Jane Fonda when she starred in Barbarella in 1968.

View this post on Instagram

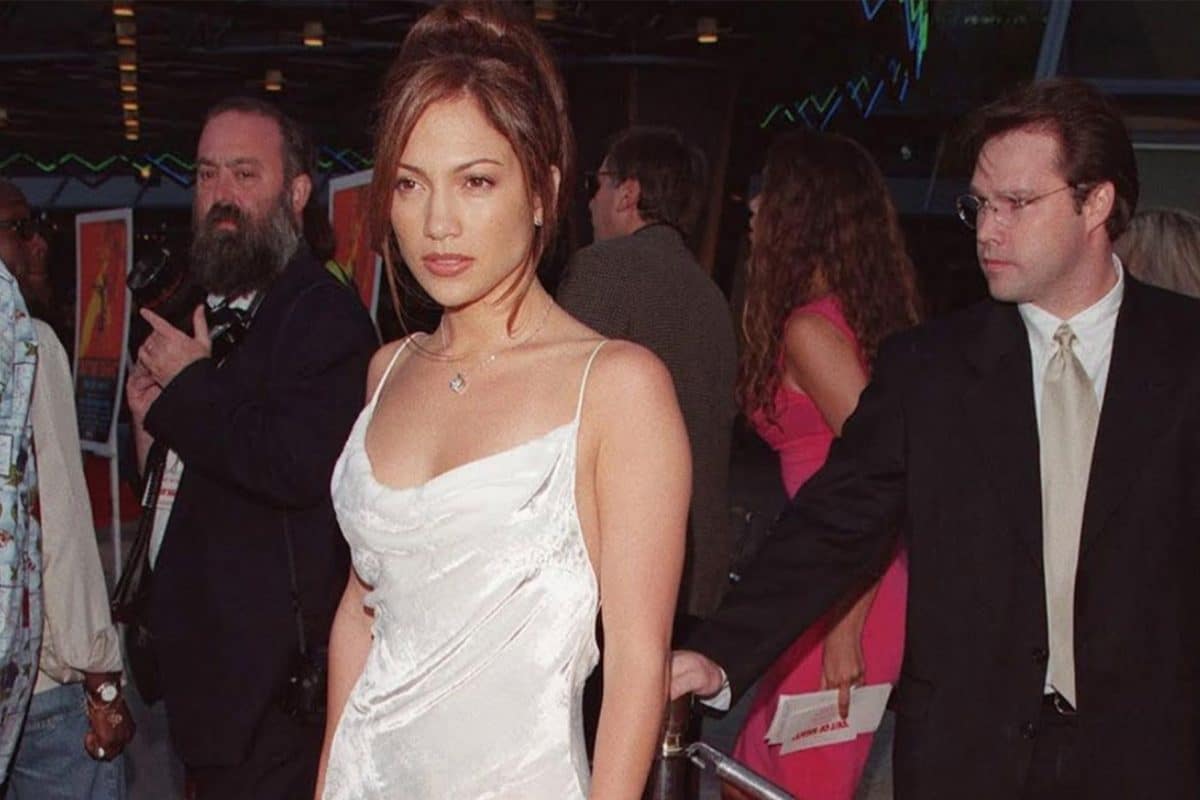

He was at the forefront of transgression in the 60s, aligning with the space-age movement that took over the fashion landscape along with fellow designers André Courrèges and Pierre Cardin. He became a go-to for It girls of the era like Audrey Hepburn, who wore one of his creations in Two For The Road, and Françoise Hardy, who was captured wearing the most expensive dress ever made at the time, one of Rabanne's gold minidresses, inlaid with diamonds consisting of 1,000 golden plaques and 300 carats. She was pictured, famously, in conversation with Salvador Dali, who once proclaimed: "There are only two geniuses in Spain: me and Paco Rabanne."

View this post on Instagram

He was part of the new guard of couturiers. Born to a seamstress mother who worked at Balenciaga and moved her family to France early in his life, his world was filled with eccentricities that made up who he was as a designer. His alignment with the space-age era was hardly by coincidence, he was a doomsayer and a numerologist. He spoke at length about having traveled from the planet Altair 78,000 years ago, and being reincarnated from his life as an Egyptian priest who assassinated Tutankhamun. He was wrapped up in Armageddon, referenced from his time reading Nostradamus, which he writes about in his two books, Has The Countdown Begun? (1994) and 1999: Fire From Heaven (1999).

Some called him "Wacko Paco", others a dreamer and a believer, one that was always chasing an alternative truth to make sense of a senseless world. But his legacy is not in his endearing eccentricities – some of which included supporting hospices for people with Aids with the proceeds of his work – it is in his ability to see fashion through another lens, to reshape the meaning of couture through material and industrialism. For this, he will always be remembered. “I will always have a place in the history of fashion” Rabanne declared in 2002. “It is required for one reason–I am in all of the dictionaries because I introduced new materials to the world of fashion. To have created the first dresses in metal, paper, molded plastic–that is my legacy.”