The morning light spreads itself across the Bay of Naples with a disarming intensity. Reflecting against the limestone facades of Via Partenope, the sea enables a rhythmic hum – from fishermen starting their day to steady stream of jogging tourists – the kind that gives a sense of being suspended between calm and combustion.

On the terrace above, Max Mara’s Creative Director for over three decades, Ian Griffiths, is looking every inch the cool-hunting Englishman in his summer suit on the eve of presenting his Resort 2026 show. “Naples is all fire and spirit,” he says looking out on the horizon to a motionless and patient Mount Vesuvius. “People live here every day as if it were their last — and you can feel that energy in the air. There are historical reasons for it, of course — earthquakes, plagues, eruptions — but what’s beautiful is the way people keep rebuilding. That desire to start over is what Naples is about. You feel it everywhere.”

Somewhat of a regular visitor in the lead up to this show they’ve “been working up towards for a long time”, Griffiths first stayed in Naples during the pandemic when Max Mara staged their Resort show on the island of Ischia. “In the height of the pandemic, the hotels were closed, so we had to stay here instead. I fell in love with the city. We swore that one day we’d come back and do a show properly — and here we are,” he smiles. “There’s something about Naples — the energy, the colour, the sound. It’s a city of resilience. And I wanted to celebrate that.”

“In the height of the pandemic, the hotels were closed, so we had to stay here instead. I fell in love with the city. We swore that one day we’d come back and do a show properly — and here we are.”

La Reggia di Caserta just North of Naples – the largest Palace erected in Europe in the 18th century and now the most significant former Royal residence in the world at over 47,000 square meters, commonly referred to as ‘a kind of swan song to baroque’ – is the chosen setting for the collection Griffiths has named Venere Vesuviana. With Gwyneth Paltrow and Sharon Stone flying in to witness the moment, Griffiths admits he was not afraid to do something majestic.

“The setting is the most beautiful I could think of,” he says casually. “But I had a decision to make: do I work with the setting, or do I work in contrast to it? To work with it would have meant elaborate ball gowns — and that’s not Max Mara. So, I took the opposite path. The woman walking down those marble stairs will do so with complete nonchalance. She’ll be dressed elegantly, informally. Her setting doesn’t overpower her. She’s not intimidated because she’s confident. I’m using the setting as a foil rather than camouflage.”

In that spirit, the collection when it unfolds is strikingly contemporary. “You will see some very pronounced silhouettes,” Griffiths promised. “You can’t think about the fifties without big skirts — they go hand in hand. There are feminine necklines, decolleté, slightly off the shoulder looks. It’s an un-fussy femininity, a woman who’s getting on with her life, achieving what she wants, stopping at nothing.”

It was a confidence that came across in the casting, with models of the moment such as Achol Ayor, Angelina Kendall, Anna Robinson, Ella McCutcheon, Ida Heiner, Awar Odhiang, and Lennon Sorrenti moving through the marble halls with the composure of women who know their power. They wore a palette drawn from the city’s natural poetry: ash and stone, chalk, sand, terracotta, smoke, sky blue, volcanic black. “There’s a sensual pragmatism to it,” he says. “The colours are grounded — not sweet or nostalgic — but full of life, like Naples itself.”

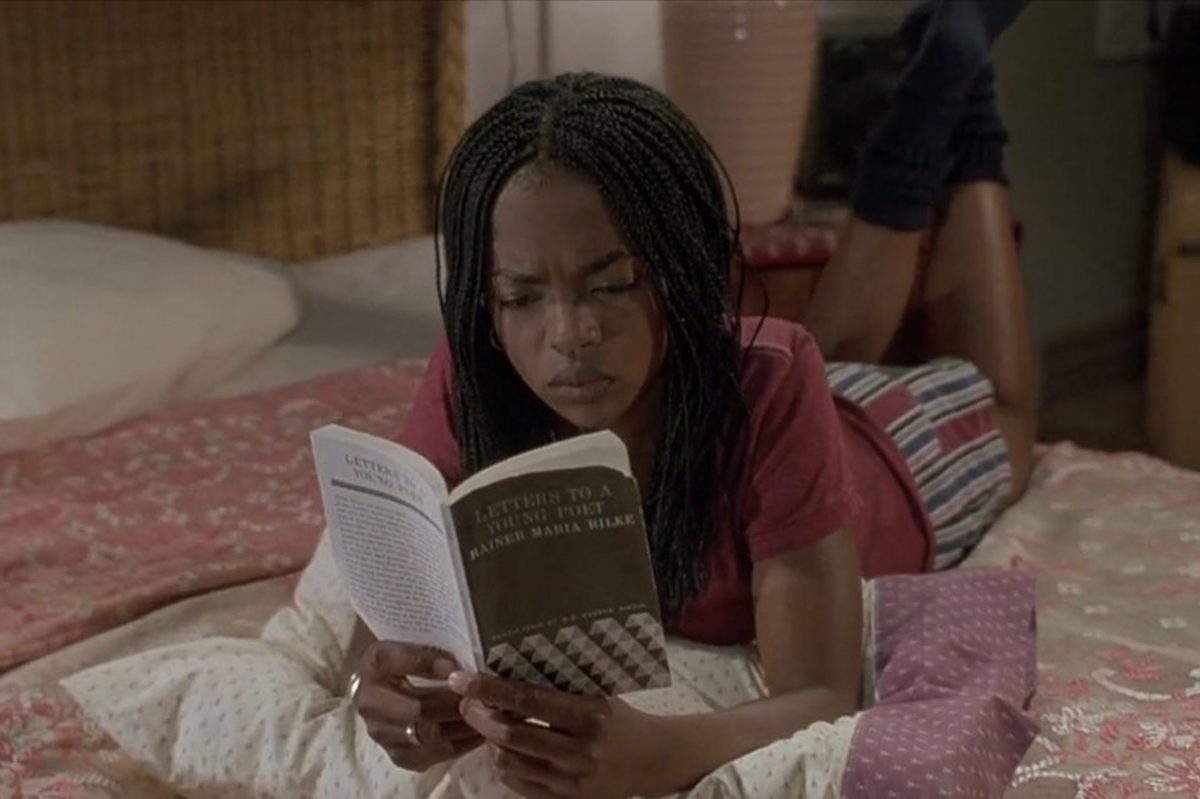

While the collection was anything but retrospective, the looks carry the echo of cinema in their attitude, hardly surprising as Griffiths spent months at home in Reggio Emilia watching the films by directors Vittorio De Sica or Giuseppe De Santis that immortalised southern Italy.

“I spent night after night watching and re-watching them. The strength that comes through — the naturalness of these women. “They didn’t have hair and makeup departments in those days”, he points out. “Very often they did their own hair and makeup, sometimes even found their own clothes. They created their own image, and they were so strong,” he says.

“Italian fashion has always been about the woman, after the war, the women were the stars. They were working, rebuilding. They needed clothes that allowed them to live. That’s the heritage I work with — clothes that give a woman the freedom to move through her life with ease and grace.”

“The woman walking down those marble stairs will do so with complete nonchalance. She’ll be dressed elegantly, informally. Her setting doesn’t overpower her. She’s not intimidated because she’s confident. I’m using the setting as a foil rather than camouflage.”

Especially Sophia Loren, who is synonymous with the Neapolitan capital. “She’s not seen so much publicly now, but her spirit is everywhere. For me, that spirit sums up the time of the Italian Renaissance following the war — the moment Max Mara was born. We’re talking about 1951. Those women were the ones who carried Italian style around the world. People talk about Italian fashion, but not French fashion as a collective idea — and that’s because in Italy, fashion wasn’t dominated by designers until the 1970s. It was shaped by brands like Max Mara — brands that simply gave women the clothes they needed to make themselves look and feel good. That’s why Italian fashion was such a success. It was elegant, easy, often with a slightly sporty edge, and it allowed women to be the frame for themselves.”

Griffiths found himself endlessly inspired by Loren’s on-screen wardrobe. “I watched Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, where she’s supposed to be pregnant, wearing a sack-like dress, and she looks fantastic. And then at a certain point, she's cooking dinner for the kids. And this sequin jacket appears, and you never find out where it came from, why she's wearing it. This black sequin jacket, and it's this mysterious sense of Bella Figura: whatever your circumstance, you find a way of beg, stealing or borrowing something that makes you look and feel good, because you know that you can be successful when you feel right.”

That philosophy drives the composition of this collection: clothes that enhance rather than impose. Lightweight tailoring made fluid by construction, trousers that replace rigidity with grace and shorts designed for motion. “A woman’s life involves much more than the office,” Griffiths says.

“When I first joined Max Mara in 1987, it was the beginning of the first phase of power dressing. Huge shoulders, big coats, always a skirt suit because women couldn’t wear trousers at work. That generation discovered they could break into the hierarchy by dressing a certain way. But since then, women have demanded more variety — more freedom. My work has been about diversification. Still clothes in which you’re taken seriously, but with options.”

"Whatever your circumstance, you find a way of beg, stealing or borrowing something that makes you look and feel good, because you know that you can be successful when you feel right.”

His work is also often a study in dualities: heritage and reinvention, the practical and the poetic. As he describes: “On the face of it, there's the woman of Reggia Emilia, this matronly family matriarch you know, holding her family together. Respectability is everything. The family turning out, looking immaculate and dressed every Sunday. And with the woman of the South, there's this kind of climate of, on the one hand, kind of repression, almost, but on the other hand of sexual availability. It’s in complete contrast to the North. The North looks kind of almost puritanical. But if you scratch the surface, it's all about Bella Figura, about looking your best.”

The accessories within the collection are a further metaphor of renewal, rebuilding and the quiet power of beginning again. “We brought back the Whitney Bag,” Griffiths says of the piece first designed in collaboration with architect Renzo Piano. “We’ve created four new designs, including an oversized work tote and smaller evening pieces. They have that same architectural geometry but with softness now — it’s about refinement, not rigidity.” Likewise, the collaboration with Marinella – a Naples born maker of silk accessories and iconic for their ties – is a fusion of friendship and tradition. “Maurizio Marinella is a friend of the Maramotti family (owners of Max Mara),” Griffiths explains. “I was aware of his work and wanted to explore the dandy aspect of Naples style — that masculine elegance. So, we made an appointment, spent the day together, and went into his archive. We found fabrics designed in 1951 and incorporated them into the collection. It was perfect — 1951, the year Max Mara was founded.”

Gesturing towards his tailored jacket, he points out. “He introduced me to Vincenzo Cuomo, a local tailor who made this suit I’m wearing. From him, I learned how Neapolitan tailors make jackets lighter — they remove some of the interfacing, some of the interlining. The result is something that moves with the body. They make tailoring that breathes. You never stop learning. There’s always something new.”