The kids in New York City in the 90s were chillin’. Watching TV, smoking pot in rundown apartments, tagging graffiti. They were hip-hop, they were grunge, they were street. Regardless of where they came from the attitude was one of lassitude; imperfection meant keeping it real, vice and decay was more than OK. The thug life, well, that was cool too.

Davide Sorrenti, on one level, was one of them. “He was a homeboy,” remembers Francesca Sorrenti of her son, laughing. “A total homeboy who spoke homeboy lingo but loved opera, rap music, to play golf, and loved basketball. He would sing opera in the shower, he loved Pavarotti and at the same time he was also about Snoop Doggy Dog.”

He was five when he moved away from his home in Naples and his father, an artist, with his mum, brother Mario and sister Vanina, all renowned fashion photographers today. His coming to America, as he told in an Avedon casting video, was about “figuring out Marilyn Monroe wasn’t Italian … And that the voice was dubbed”. Growing up in New York, however, also meant more regular treatment for his blood disorder thalassemia – one of the side-effects was to make him look much younger than his age – with a severity of which he kept hidden from most outside his family and inner circle.

This new city and life, striking in its contrast to his Mediterranean roots was a melting pot of creativity, and his mother’s loft invited it all in the door for all her children.

“New York at that time was a place that had a lot of flavour and Davide’s personality added to that,” says Mario Sorrenti of the brother he calls “super funny and charismatic”. “He was a cool kid. He saw the world in his own way and wasn’t afraid of it.”

“He was very passionate and felt very strongly about all the things that were going on around him that were enticing, like art, fashion, music,” says his sister Vanina.

“He embraced and was very much a part of the street and youth culture that was exploding at the time. He really felt part of it, and he was very involved and touched by it. It was all very different back then. We grew up at a time in New York where you couldn’t just walk around with your phone out, you had to look out and watch your back, every corner and every doorway.”

Davide’s charming way of being drew people to him wherever he went. “Once we were in Milan at a fashion show and he captivated Franca Sozzani, who is the Editor in Chief of Italian Vogue, and she invited him to sit with her at a fashion show,” recalls Francesca, still sounding surprised.

“Richard Pandiscio who was the Creative Director at Interview (magazine) at the time had met Davide once in my company at a dinner party and he was really fascinated with Davide that he decided to write a story on the ones to watch.”

Like moths to a flame, his peers, the homeboys, also gathered around him. With skateboarders and graffiti artists he started the SKE crew – his tag was Argue – a rap group called The Mosaics and streetwear label Danucht that began with what were called pimping slogan tees, with the likes of ‘Yo Bro’, ‘Down By Law’ and ‘Models Suck’ (not because they didn’t like models, but because modelling sucked). But Davide was motivated beyond all of this, he wanted to, in his own words, “know everything about everything” and he was going out with his camera and booking work as a photographer for the likes of i-D, Interview and Detour magazines.

The work influencing the time was that of Corinne Day and Nan Goldin, as well as his brother Mario, who dated Kate Moss when she first came on the scene. They were pioneers of what was edgy and beautiful, their style was blunt and raw with a hunger for authenticity; a reality in opposition to the high-glamour 80s. Because of the drugs being experimented with at the time and the waifish models they were shooting, it was labelled as ‘heroin chic’, however these photographers never believed their work to be about the glamourisation of drugs, more simply a search for something more honest and raw; the reality of the time in favour of the polished excess that had become the norm.

“Davide was for sure influenced by the people around him that he admired, such as Nan and I, but I think he definitely had his own thing going,” says Mario. “He was very artistic, he spent a lot of his time drawing and painting in oils, he kept diaries filled with ideas. He was deep and introspective. He had creativity flowing through his veins.” According to Vanina, this was led by his very strong personal point of view. “He depicted and captured what was going on around him and sometimes he could be dark but then he would find the irony, fun and light and the beauty in it,” she says. “He

could turn it around.”

Francesca can’t remember her son without his camera.

“No matter what, where, he always had his Leica with him and he had this amazing ability to keep a really firm hand – because you know he was also an artist, he used to paint things that were really beautiful – and so he was able to really hold that camera steady. And I think that he truly depicted kids in the 90s,” she says.

“It was funny because I remember coming out of the cinema with friends and Larry Clark had done that movie Kids. Davide’s words were ‘it was really whack’ and all his friends were saying Davide should have shot that movie.”

When Davide died tragically at just 20, his death became a catalyst for the call to end heroin chic, and his work would be forevermore associated with it. Even though he died due to his thalassemia, he was seen as a representative of the scene at the time, along with his girlfriend model Jaime King (now a successful actress and television personality), who’d admitted to being caught up in drugs in her early modelling days.

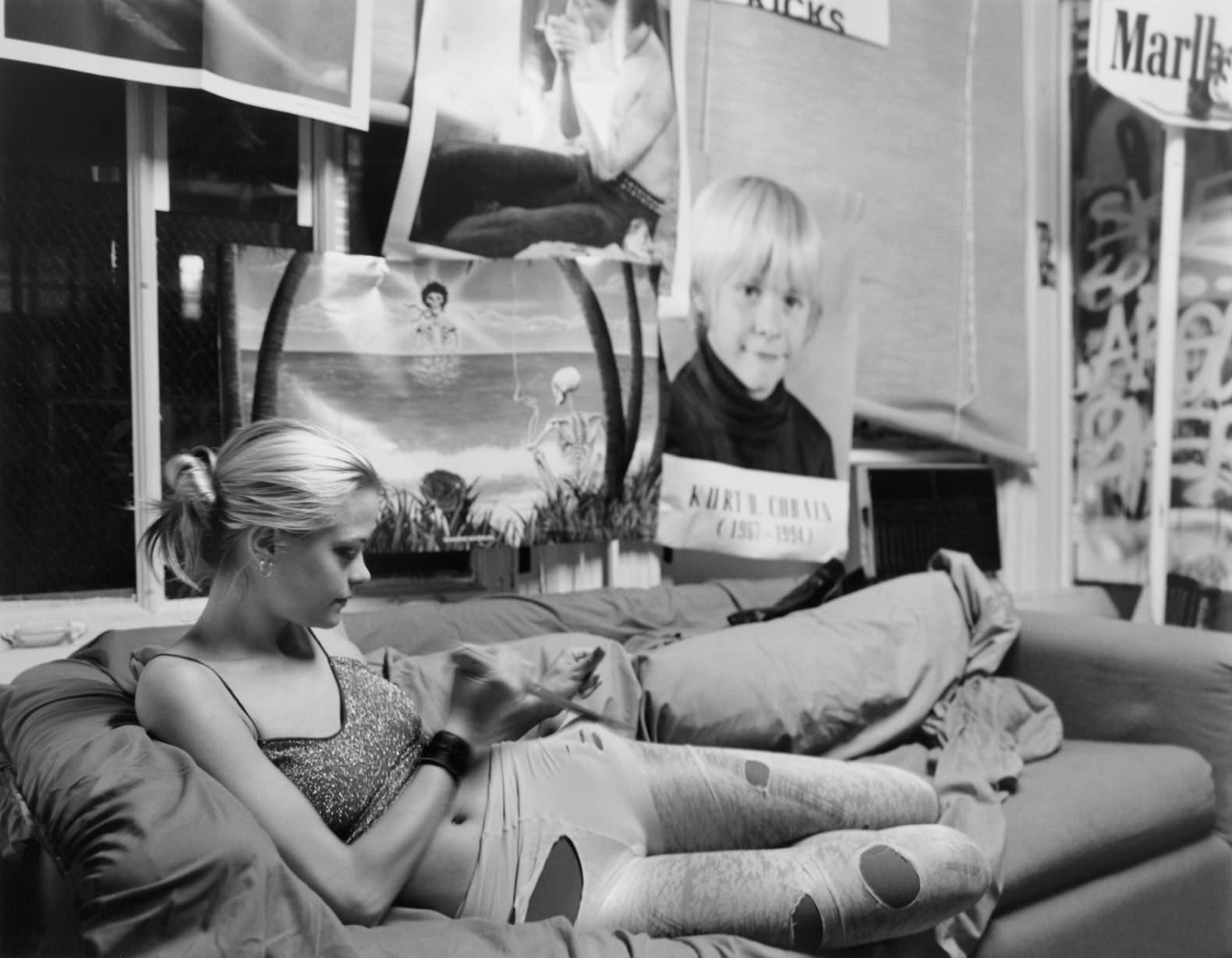

Earlier this year, days after Davide would have turned 38, she posted the image of herself shot by him surrounded by posters of Kurt Cobain and Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead. She commented: “‘Oh Davide, we got into so much trouble with this picture. At least we know the depth of what we were capturing. #lostart #thislifeisprecious.”

“You know it’s funny because at the time he took that very druggy picture of Jaime, he didn’t do drugs,” says Francesca.

“He took it to show what the day’s youth was doing. In fact, I was at home and he asked me … He’d ripped up her stockings and he’d put in the Kid Vicious picture and I said, ‘God, you’re taking this too far’. And sadly that really depicted his life but it really wasn’t at the time.”

Vanina, whom he collaborated with a lot, was there when he shot the picture. “You could call and label that era in so many different ways but we weren’t necessarily aware of that aspect. We were all there living it as an experience,” she says. “In reality this wasn’t the norm, we were exploring and breaking boundaries, wanting in one way or another to express ourselves and communicate what we were feeling and simply wanting to have a good time through it all.”

Mario (who captured Davide’s illness in his book The Machine), also believed the reality to be very different. “The media likes to sensationalise pain and tragedy. For us it was a very personal and painful loss. Davide was not a victim of fashion, he was a young boy struggling with his illness at a point in his life when he was growing up and maturing into a young man.”

He smoked a lot of weed, says Francesca. “Because of his illness, it helped with the pain, but he wouldn’t tell anyone that. Everybody thought he smoked because he was hip and cool,” she says. “He was very ill, he needed blood transfusions every two weeks in order to survive.”

“Davide knew that he was dying but no one would have known this from his physicality because he was so incredibly strong mentally and never surrended to his illness,” says Vanina.

“He did everything he wasn’t supposed to do. He wasn’t supposed to eat red meat, and he ate red meat. He wasn’t supposed to play too many sports and he would play every single sport he wanted, and thrive at it. He did everything he wanted to do because he knew he wasn’t going to be around much longer. Everything for him was precious because the life expectancy of someone with thalassemia in the 90s was 25, he was already an old man.”

Hundreds of people showed up to Davide’s funeral, magazines like Detour stopped the presses to write his eulogy and people from all over the world, such as Colette in Paris, were contacting Francesa about exhibitions or just to say they’d been touched by him. Her belief is that because a tragic death through his illness was imminent, this was almost meant to be. “Fashion history books talk of Davide as ending heroin chic, so all across the board, he helped a lot of friends, a lot of people he didn’t know and he helped me fight a battle against it,” she says.

“The most compelling thing was that one day a really important journalist (Amy Spindler), turned up on my doorstep and she’d met Davide and said that this thing with heroin has gotten so out of hand within the (fashion) business that we needed to talk about it. I sat and I spoke to her and before I knew it, three days later Davide’s picture is on the front of The New York Times.” Shortly after, President Clinton made a speech denouncing the look and while he didn’t mention Davide by name, it was in response to media around his death.

Now, on the 9th of July every year, Davide’s birthday, his family and friends come together to have a big party. “They come with their kids, with their girlfriends, their wives … They all feel they are who they are today because Davide opened doors for them,” says Francesca.

“When Davide passed away, it was as if he shed light on everybody. Everyone made a 360 turn, including myself,” says Vanina. “He opened everybody’s eyes to life. He knew he wouldn’t be able to grow old or have family and take time to live an ordinary life with the people he loved and he had known that since he was very young. Someone who is faced with death since they are born is a different kind of person. They can see beyond what’s there and that was the beauty, he saw more of what was around him. And people loved him because of that.”

While the Argue tags around New York City have all faded, his legacy still burns brightly. There remains a huge scope of people who knew him and were touched by him, and others that are just fascinated by the story of what looked like this normal kid. Perhaps because of his illness he was always very comforting to people who had shortcomings, to kids that had problems and to girls that weren’t to the standard of fashion models. “I met many girls who said they loved Davide because he was kind to them, “says Francesca. “One girl said that they’d called her fatty and that Davide would stick up for her and take her into the club with him.

“He used to say that fashion models were like swans, they were particular kinds of birds, not your everyday sparrow.” She laughs, “He had a funny way of saying things.”

By only 20 he had touched so many people from all walks of life and left work behind him that most people have their lives to complete.

“It’s unbelievable, he saturated life in a way,” says Vanina. “We take these moments for granted but every moment for him was precious, so he tried to live every single moment to the fullest. He would have this incredible irony and humour and pick out all the best and worst sides of people and glorify them, right in front of their eyes. People just loved it because he made them feel alive and human. He just really acknowledged people and things around him.”

Images copyright Davide Sorrenti. A very special thanks to the Sorrenti family. Watch the trailer for the feature length documentary on Sorrenti's life, See Know Evil, here.